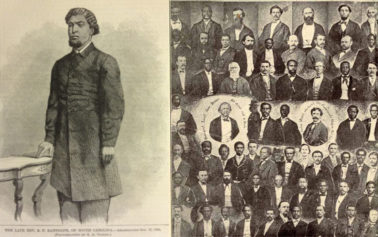

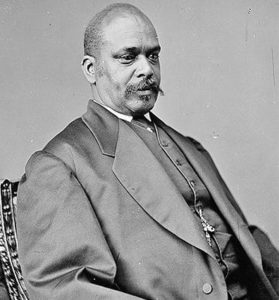

Oscar James Dunn fell mysteriously ill around the peak of his political career. (Image courtesy of Wikipedia.)

Oscar James Dunn was elected the nation’s first Black lieutenant governor but his legacy would go unnoticed, as Louisiana never erected a statue in his honor.

Local man and Dunn descendant Brian Mitchell is now trying to change that. Speaking with Splinter News, Mitchell said growing up, he had no idea his great great great-uncle was the first Black lieutenant governor not just in Louisiana but the whole nation. He recounted the time his teacher told him the state had never had an African-American lieutenant governor when he was just 8 years old.

It was the family stories told his great-grandparents told, however, that led him to uncover his roots. ”

“…As I child, I’d spend my days after school with my great-grandmother,” he told the news site. Her stories “always sort of lead to important patriarchs or matriarchs,” including Dunn.

Mitchell is now a college history professor and has spent much of his career studying Dunn.

New Orleans, along with several other cities across the nation, was recently thrust into the spotlight over its removal of four Confederate statues following a raucous white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va. Mitchell is focused on statutes too, but namely the one that was intend to honor his late relative. It was never built, however.

During his relatively short life, Dunn made a name for himself challenging white politicians over civil rights, and driving a strong civic force to promote education and youth initiatives for emancipated Blacks. He even offered his services to freedmens seeking work on farms after the Civil War, making sure they weren’t cheated and actually paid for their work.

Believing he might make a good politician one day, those close to Dunn encouraged him to run for public office. He was elected lieutenant governor of Louisiana in 1868. Dunn was a member of what was then known as the Radical Republican party.

“They were the progressive party that was trying to extend civil rights to Black Americans, especially in the South,” Nick Weldon, who works for the Historic New Orleans Collection, told Splinter News.

Weldon got his hands on a few historic documents detailing Dunn’s history, including clippings from the New Orleans Times. In one quote, local Democrats characterized the Black man as the “taint of honesty and of scrupulous regard for the official properties,” which was a “serious drawback in innervating a reproach on the lieutenant governor.”

Dunn served alongside Gov. Henry Warmoth, who he thought shared his common goal of achieving equality between Black and white Louisianans. The pair were also members of the same anti-racism party. When Warmoth refused to sign legislation to protect Blacks, however, it caused a major fallout and split the party.

“It was complete chaos,” Weldon said. “There was no order.”

Warmoth began losing power and there was even talks of impeachment. Meanwhile, Dunn continued winning the public’s favor. Rumors also started to swirl that President Ulysses S. Grant was considering him for vice president after his visit to the Capitol.

That would never come into fruition. Dunn attended dinner party one night and became violently ill, dying just two days later, according to the news site. Many suspected he was poisoned. His family refused an autopsy.

While $10,000 was dedicated for a monument honoring Dunn after his death, Weldon said it was never made and no one knows why.

“When you see this somewhat rising African-American political star at the time of all this strife … The guy dies and pretty much with him was all the gains that he had fought for: Civil rights, suffrage, integration in public schools,” he said.

Mitchell said he believes a monument honoring his great great great-uncle “definitely” would have made a difference in how well-known he was.