It sounds like a good idea and, in theory, it is. More than 600 correctional institutions across the country now offer inmates and their loved ones the ability to “video visit” through the provision of video-calling services. For America’s correctional industry, the benefits of employing this virtual technology are numerous, including greater security, less visitor vetting and strip searches for weapons and drugs, and less associated manpower and costs. Additional revenues are generated from this virtual process as correctional institutions commonly receive a portion of the video-calling revenues. Plus, families who live a long distance from their incarcerated loved ones can now visually interact with them on a regular basis.

However, this ostensibly good idea belies a darker reality. “In practice it’s very different,” said Hannah Riley, communications manager for the Southern Center for Human Rights. Riley, who holds a master’s in criminology from the University of Cambridge, has researched and written on criminal justice policy, the death penalty and wrongful conviction. “A lot of jails that start to implement video visitation do it at the expense of in-person visitation at all, which is incredibly problematic.”

The Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) reported 74 percent of correctional facilities that adopt video visits end up reducing in-person visits or doing away with them altogether. This increasing trend has occurred despite studies that have consistently detailed the positive effects of in-person visits on inmates and families, and on curbing recidivism. Prison telecom industry leader Securus has even required correctional facilities to cease in-person visits upon contracting their services. The institutions that do so offer onsite video-calling for free, or remote video-calling for a cost that varies by institution, provider and location.

“There’s an enormous amount of money to be made off of this,” stressed Riley, noting “for a lot of people already facing the other costs of having an incarcerated loved one, that’s just not feasible.” The Ella Baker Center reported that over a third of families go into debt from attempting to cover the costs of communicating with their incarcerated loved ones, a burden disproportionately shouldered by poor and African-American families given their over-representation in the criminal justice system. For major companies like Securus — who literally bank on a captive audience and commonly win exclusive contracts with a state or county by channeling a portion of their profits back to the local correctional institutions — remote video-calling for inmate families, on average, runs $1 a minute. Despite these substantial fees, there have been widespread complaints from families about the considerable technological requirements and sometimes prohibitive quality of the video services offered, a problem exacerbated by the fact consumers often pay in advance.

“The people most likely to use prison and jail video visitation services are also the least likely to have access to a computer with a webcam and the necessary bandwidth,” reported Bernadette Rabuy and Peter Wagner, in a PPI study on video visitation. “It is clear that video visitation industry leaders have not been listening to their customers and have not responded to consistent complaints.”

Onsite video visitation at jails has been subject to ongoing complaints as well given the counterproductive nature of a video screen for families who have traveled to be in the same physical location as their loved ones. “I can’t imagine the scenario in which someone would travel to a prison and then wish to communicate through a video screen rather than see a prisoner face-to-face,” quipped Illinois Department of Corrections spokesman Tom Shaer to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Yet some don’t see a problem. “Video visitation is a wonderful tool that increases the quality of an inmate and friend/family member visit,” wrote Richard A. Smith, CEO of Securus, in a 2015 statement. Smith claimed “it saves both inmates and friend/family members money and time, saves officer time, and makes facilities safer, all things that are important to us and all of our customers.”

However, regarding increased safety, existing studies have said otherwise. A 2014 case study on the jail in Travis County, Texas, found that “total disciplinary infractions and incidents increased, as did assaults, within the year after the elimination of in-person visitation. Possession of contraband infractions also increased.”

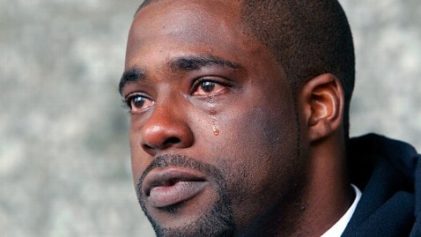

Not a surprise for some. “The opportunity to sit face to face and just have a personal connection is the one reprieve you get in all of this,” said Jaynna Sims, former girlfriend of a Texas inmate, in a 2016 interview with Mic magazine. “But once you take away in-person visitation, you don’t have that. It’s like the system keeps finding ways to victimize people. And how can that, in any way, heal an individual, or a community?”

Sims’ point drives home the emotional impact on inmates of denying such face-to-face- contact. But what of the legality of the policy? Shouldn’t inmates have the right to in-person visits from their loved ones and not be forced to communicate by video-visit?

Not according to Richard Van Wickler, the superintendent of the Cheshire County Jail in New Hampshire, a client of Securus. Last December, Van Wickler told National Public Radio, “When one violates the law, and one has to serve time in a public institution, one of the liberties that one could lose is the opportunity to hug a loved one.” Yet given video visitation services are far more likely to be adopted and employed by local jails than prisons, such ‘violations’ are commonly undetermined, as jails house a more temporary population whose proximate cause of incarceration is being unable to afford bail. Seventy percent of those in jail haven’t been convicted of a crime.

After referencing United Nations and international rules that indicate in-person visitation to be a human right, Riley explained “those rules aren’t legally binding for the United States.” She also pointed to American Correctional Association guidelines that recommend that such video technologies be employed “as supplements to existing in-person visitation” and “should not place unreasonable financial burdens” on inmates and their loved ones. “But these are just guidelines,” clarified Riley. “Without a national legal framework or something coming down from the Supreme Court, the decision always goes back to local authorities.”

Some local authorities have stepped up. Recent legislation in Texas requires that in-person visitation be maintained in jails. California has passed similar laws as well. Riley hopes more states will follow suit. “Any way one can be more in touch with incarcerated loved ones is a good thing.”

That said, continued Riley, “I think our best hope is, someday, having some kind of national legal framework that mandates that in-person visitation is a right that every prisoner has.”