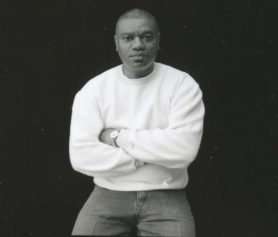

Wilbert Jones talks to media with his brother Plem Jones, right, after leaving East Baton Rouge Parish Prison in Baton Rouge, La., (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

BATON ROUGE, La. (AP) — A 65-year-old man who was arrested at 19 and sentenced to life without parole walked out of prison on Wednesday, saying “God is so good” after his rape conviction was overturned by a judge.

Authorities withheld evidence that could have exonerated Wilbert Jones decades ago and their case against him was “weak at best,” State District Judge Richard Anderson said.

“Freedom. After more than 45 years and ten months. That’s going through my mind,” Jones said as he hugged his brother, Plem Jones, and other relatives outside the gates of the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison.

Jones also thanked his legal team at the Innocence Project New Orleans, saying “without them, this wouldn’t be possible.”

Doing all that time was “very difficult,” Jones said, but he told reporters he holds no resentment.

“I forgave. I forgive,” Jones said. “I didn’t have control of it. Why should I worry about it? I’m in charge of myself.”

Wilbert Jones leaves East Baton Rouge Parish Prison with Emily Maw, director of Innocence Project New Orleans, left, and Kia Hayes, IPNO staff attorney, in Baton Rouge, La., Wednesday, (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Attorney Emily Maw praised “the extraordinary strength” of a man “who has spent over 16,000 days in prison for something he didn’t do,” and would nevertheless “come out with a faith in God and in humanity.”

Prosecutors said they do not intend to retry Jones, but they also said they would ask the Louisiana Supreme Court to review last month’s decision by the judge. Court spokesman Robert Gunn said Wednesday morning that no such request had been filed. Jones has yet to be cleared; the judge set his bail at $2,000.

Maw told The Associated Press that it would be “legally incorrect and morally problematic” if the East Baton Rouge District Attorney’s Office insists on trying to uphold the conviction, because by doing so, it would be “saying that when Wilbert Jones was arrested in 1972 as a young, 19-year-old poor black man, he did not deserve the rights that people deserve today.”

The district attorney’s office did not immediately respond to the AP’s request for comment.

Jones was arrested on suspicion of abducting a nurse at gunpoint from a Baton Rouge hospital’s parking lot and raping her behind a building on the night of Oct. 2, 1971. He was convicted of aggravated rape at a 1974 retrial that “rested entirely” on the nurse’s testimony and her “questionable identification” of Jones as her assailant, the judge said.

The nurse, who died in 2008, picked Jones out of a police lineup more than three months after the rape, but she also told police that the man who raped her was taller and had a “much rougher” voice than Jones had.

Jones’ lawyers claim the nurse’s description matches a man who was arrested but never charged in the rape of a woman abducted from the parking lot of another Baton Rouge hospital, just 27 days after the nurse’s attack. The same man also was arrested on suspicion of raping yet another woman in 1973, but was only charged and convicted of armed robbery in that case.

Anderson said the evidence shows police knew of the similarities between that man and the nurse’s description of her attacker.

“Nevertheless, the state failed to provide this information to the defense,” the judge wrote.

Jones’ attorneys also said that a prosecutor who secured his conviction had a track record of withholding evidence favorable to defendants. A 1974 opinion by a state Supreme Court justice said the prosecutor was responsible for 11 reversed convictions the preceding year — “an incredible statistic for a single prosecutor.”

Prosecutors denied that authorities withheld any relevant evidence about other Baton Rouge rapists.

“The state was not obligated to document for the defense every rape or abduction that occurred in Baton Rouge from 1971 to 1974,” prosecutors wrote in February.

Jones’ attorneys described him as a “highly trusted prisoner and a frail, aging man” who poses no danger to the community. Prison warden Timothy Hooper also testified for his release, calling him a model inmate. The late nurse’s husband wasn’t opposed either.

“He feels that Mr. Jones has been in prison long enough and that he should be able to get out and spend his remaining years with his family,” the lawyers wrote.

Plem Jones figures he may have missed one or two bimonthly visits with his brother in prison over the years.

“We’d sit and talk, and cried together,” he said. “I never gave up on it. I knew that he didn’t do it, so, you know, it wasn’t nothing but a matter of time. I knew that he was going to be freed one day. But I just didn’t know when. I thought it was going to be long before now.”

___