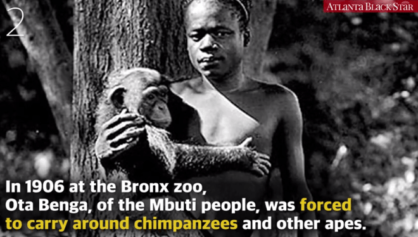

Reggae singer-songwriter King Mas isn’t like a typical star of the genre. A member of the conscious reggae fusion movement, his work aims not just to entertain but to heal. So his tune about Ota Benga, a Congolese pygmy whose village was slaughtered before he was captured, enslaved and put on display at various American zoos, is a natural fit.

“‘Ota Benga Smile’ is a look at an aspect of our story as Africans in America that forces us to face the horrific reality that we were widely considered ‘scientifically’ subhuman until relatively recently,” King Mas explained of how this song relates to conscious reggae fusion, which is also known as reggae revival. “Using a Reggae/Hip-Hop beat (produced by my brother Mitymaose) as a vehicle to deconstruct Ota Benga’s experience and how it ties into our current situation in America, created a perfect medium for healing through sound vibration.”

Filmmaker and photographer Alexander Fort was tapped to direct the music video, which premiered on YouTube Monday, Oct. 30. Fort said Mas was inspired to tackled Benga’s story after reading the biography, “The Pygmy in the Zoo.”

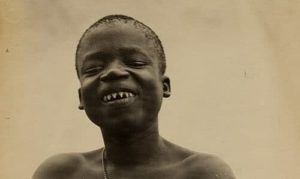

“The thing that stuck out to him was that in all the pictures you can find of him, he is smiling in most,” Fort said. “I found it intriguing that throughout all the horrors and tragedies that Ota Benga went through nothing took his smile from him.”

Ota Benga’s teeth shapes were the result of his right of passage. (Missouri History Museum/Jessie Tarbox Beals/Wikimedia Commons)

With lyrics about being trapped in a cage for “so long I don’t remember why,” the song captures what Benga’s life was like in an enclosure with primates at the Bronx Zoo. The video highlights Benga’s emotions by relying on lighting and a shaky camera as Benga, played by 16-year-old SeeFour, escapes from captivity. He’s able to do so after an Obeah man, played by King Mas (who also plays the King in the forest), gives him the strength to break out of the cage and escape.

While the clip shows Benga being welcomed by the King after successfully returning to his home in the Congo — public outrage led to real-life Benga’s release in 1906 — he fell into a depression after he was unable to return home during World War I. In 1916 at age 32, he build a ceremonial fire and died by suicide after shooting himself in the heart.

“For the music video, we really wanted to celebrate what we perceived as the strength of his character,” Fort said before explaining what led to the real-life Benga being used for entertainment. “I don’t think a lot of people could imagine having troops from a foreign country murder your wife and kids while you are off on a hunting expedition. You are completely devastated [by] your loss. Then you get captured and sold into slavery. Then eventually put on display as a savage in a zoo surrounding by animals.

More On Human Zoos

13 Shameful Pictures of Europeans Placing African People in Human Zoos

You Would Be Shocked At The Amount Of Visitors Human Zoos Got In The Early 20th Century

Norway to Re-Create Exhibit of Africans in Human Zoo During National Gala

“We also wanted to symbolically welcome Ota Benga home,” Fort added. “He passed away still missing home in the Congo, in the forest’s he grew up in. Based on that, we decided the music video’s storyline would highlight the strength we felt from him and bring Ota Benga home, to allow his soul some rest.”

King Mas said having Fort on board as a video director has always been a “mystical and powerful experience.” “Ota Benga Smile” is the second clip the two have collaborated on, the first being “Walk Like A Champion (Remix).”

“He has a keen eye for symbolism and a willingness to step into some locations that many other videographers would likely shy away from,” the Grammy-winner said. “We are both deeply rooted in our community in Boston and I knew that a combination of our talents and connections would bring together the right elements to make the ancestors proud.”

He hopes the visual moves Black Americans to reconnect to the motherland.

“I would be elated to see this visual on a broader platform because often times we separate the African-American experience from the continental African experience,” he said. “A story like this, presented through a compelling visual, fosters a greater feeling of interconnection between the continent and the diaspora. It would be an honor for this song/video to play a large part in the movement to reconnect the extremely diverse Bantu nation around the globe.”