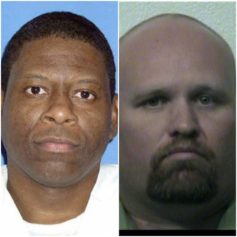

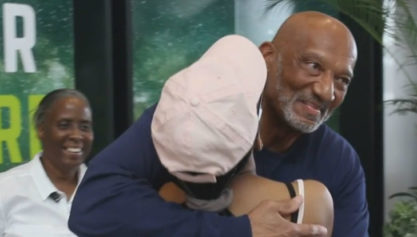

Lamonte McIntyre, who was imprisoned for 23 years for a 1994 double murder in Kansas that he always said he didn’t commit, walks out of a courthouse in Kansas City, Kan., with his mother, Rosie McIntyre, after the district attorney dropped the charges. Kansas legislators expect to consider proposals next year to make it easier for people wrongly convicted of major crimes to win compensation from the state. (Tammy Ljungblad /The Kansas City Star via AP, File)

WICHITA, Kan. (AP) — Rose McIntyre says she wonders whether her refusal to grant regular sexual favors to a white detective prompted him to retaliate against her black son, who spent 23 years in a Kansas prison for a double murder he didn’t commit.

“I do believe that if I had complied with his request for me to become his ‘woman,’ that my son would likely not be in prison,” she said in a 2014 affidavit.

Her son, Lamonte McIntyre, 41, walked out of a court hearing on Oct. 13 a free man after Wyandotte County District Attorney Mark Dupree asked that charges from the 1994 murders be dismissed because of “manifest injustice.”

The case has outraged, but not surprised, the poor black community of Kansas City, Kansas, and highlights why many African-Americans do not trust police and the U.S. criminal justice system.

“In my community, this is a norm,” Lamonte McIntyre said Saturday in a telephone interview. “We are not shocked or surprised at the injustice or the brutality … of law enforcement. This is an everyday life for us.”

Documents made public during an 8-year effort to exonerate Lamonte McIntyre allege homicide detective Roger Golubski used his power to prey for decades on African-American women, including Rose McIntyre. They also accuse the prosecutor in the case, Terra Morehead, of intimidating witnesses who told her McIntyre was not the killer. And they say the presiding judge, Wyandotte County District Judge J. Dexter Burdette, had a romantic relationship with the prosecutor before the trial that neither disclosed at the time.

None of them has faced discipline. Golubski rose through the ranks to detective and captain. He retired from law enforcement last year. Morehead is now a federal prosecutor in Kansas City. Burdette is still on the bench.

Golubski’s attorney, Paul Morrison, did not respond to multiple phone and email messages left at his law office seeking comment. Morehead did not respond to an email and the U.S. attorney’s office declined comment. Burdette did not return a message left at his office.

Lamonte McIntyre was 17 when he was given two life sentences for the 1994 murders of Doniel Quinn, 21, and Donald Ewing, 34. They were shot in broad daylight as they sat in a car in a drug-infested neighborhood of Kansas City. No physical evidence linked him to the crime, and he didn’t know the victims.

When police showed eyewitnesses a photo lineup of five people to identify the shooter, three of those photos were Rose McIntyre’s relatives — her two sons and a nephew.

At the trial, two planned eyewitnesses to the murders told Morehead when they saw Lamonte McIntyre in person that she had the wrong man, according to court filings. Niko Quinn signed an affidavit that she lied on the stand because Morehead threatened to have her arrested and have her children taken away if she did not testify. Morehead sent the other witness, her mother Josephine Quinn, away without calling her to testify. Those exculpatory statements were not disclosed at the time to Lamonte McIntyre’s defense lawyers.

Another witness, Ruby Mitchell, signed an affidavit attesting to her fear of Golubski. On the ride in the police car to the station to identify the suspect after the shootings, Golubski made sexual comments to her and asked if she dated white men, according to the affidavit.

Rose McIntyre recounted in her affidavit that Golubski coerced her into a sexual act in his office in the late 1980s and then harassed her for weeks, often calling her two or three times a day, before she moved and changed her phone number.

“He had total power, and I was terrified that he would try to force me again to provide sexual favors,” she said in the affidavit. “I also knew that there was no one I could complain to, as Golubski was known to be very powerful in the community and in the police department.”

Golubski was so involved with black female prostitutes and drug addicts that he fathered children with some of them, according to an affidavit from retired police officer Ruby Ellington, a 25-year Kansas City police department employee.

“Roger Golubski’s involvement with them was no secret,” Ellington said. “It was simply accepted as part of what Roger Golubski was able to do without repercussion.”

Kansas City Police Chief Terry Zeigler said in an emailed statement that the FBI looked into Golubski’s conduct and could not find any incidents within the statute of limitations, which is five years for such allegations. They consider the matter closed. Zeigler added that he worked with Golubski and “never saw anything that caused me concern.”

A leading expert on legal ethics said the romantic relationship between the judge and prosecutor amounted to judicial misconduct and also deprived Lamonte McIntyre of his constitutional right to a fair trial.

“It is hard to imagine a circumstance in which a judge’s impartiality would be more open to question than where a judge has been intimately involved with counsel for a party — in this case, the government prosecutor,” wrote Yale Law School attorney Lawrence Fox, in a report to help exonerate McIntyre.

Community activists are calling for independent investigations. The Wyandotte County district attorney’s office said it has asked the Kansas Bureau of Investigation to look into the case.

The Midwest Innocence Project is taking “a hard look” at more than a dozen suspect cases in their database that involved Golubski, said Tricia Bushnell, the group’s executive director and co-counsel for McIntyre.

“This is an entire community that has suffered,” Bushnell said. “And until we hold all of these different parts of the system accountable, none of them get justice.”