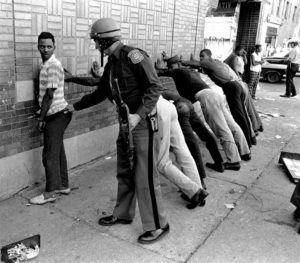

Michigan State police officer searches a youth on Detroit’s 12th Street where looting was still in progress after the previous day’s rioting. (AP Photo/File)

CORRALES, N.M. (AP) — Nearly 50 years after the Kerner Commission studied the causes of deadly riots in America’s cities, its last surviving member says he remains haunted that its recommendations on U.S. race relations and poverty were never adopted.

But former U.S. Sen. Fred Harris of Oklahoma also said he’s hopeful those ideas will be embraced one day, and he’s encouraged by Black Lives Matter and other social movements.

In an interview with The Associated Press, the 86-year-old Harris said he still feels strongly that poverty and structural racism enflame racial tensions, even as the United States becomes more diverse.

“Today, there are more people in America who are poor — both in numbers and greater percentage,” Harris told the AP from his home in Corrales, New Mexico. “And poor people today are poorer than they were then. It’s harder to get out of poverty.”

The nation’s poverty rate was 14.2 percent in 1967 compared to 14 percent last year, according to the U.S. Census.

And despite five decades of civil rights and voting rights advancements, cities and schools “have re-segregated,” Harris said. He cited recent federal data that showed the number of poor schools with mainly Latino and black students more than doubled from 2001 to 2014.

The resulting tensions sometimes play out in clashes with police, as seen recently in St. Louis, Baltimore and Charlotte, North Carolina.

Only by getting the general population concerned about racial disparity, poor housing and proper job training will the United States finally tackle the underlying causes of the urban riots of the 1960s and the police-minority tensions of today, Harris said.

“We can help people to see that we didn’t solve these problems,” Harris said. “No, they are still with us, and in some ways, poverty is worse.”

Of the Kerner Commission’s members, who included former Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner, New York Mayor John Lindsay and U.S. Sen. Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts, only Harris remains.

The late President Lyndon Johnson created the 11-member commission in 1967 as Detroit was engulfed in a raging riot. Five days of violence would leave 33 blacks and 10 whites dead, and more than 1,400 buildings burned. More than 7,000 people were arrested.

During the summer, more than 150 cases of civil unrest erupted across the United States.

With other commission members, Harris toured riot-torn cities and interviewed black and Latino residents and white police officers. Harris and his colleagues soon discovered that as black residents from the South moved into urban centers, white residents moved out and so did high-playing employment opportunities.

“Over and over, we were told, ‘we want jobs, baby,’ Harris said.

The panel concluded that the nation should spend billions revitalizing struggling cities, improving police relations and ending housing and job discrimination.

But amid the Vietnam War and anti-war protest, Johnson refused to meet with the commission. Johnson concluded the report would “ruin” him and that commission members didn’t give his “Great Society” programs enough credit, Harris said.

“That was false,” Harris said, arguing that the report gave Johnson credit for tackling poverty and wasn’t aimed at hurting him.

Nonetheless, the report, released March 1, 1968, became a bestseller and a classic study on poverty and racial inequality in the U.S.

Eric Tang, an African and African Diaspora Studies professor at the University of Texas, said that before the Kerner Commission report, no government document had explicitly named institutional, systemic racism as an underlying cause of black unrest in the U.S.

“These issues haven’t gone away because many of the key recommendations weren’t implemented,” Tang said.

After President Richard Nixon took office, the focus shifted to increased policing in cities and confining the poverty there, Tang said.

In recent years, high-profile police shootings of unarmed black and Latino men have sparked multiple urban racial conflicts, protests and calls for police reforms.

Last year, then-San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began taking a knee during the National Anthem before football games to protest the shooting of black men by police. Other NFL players joined, prompting President Donald Trump to declare that any football player who continued to do so should be fired.

Ronnie Dunn, an Urban Studies professor at Cleveland State University, said since many of the issues remain around racial inequality, the Kerner Commission “could have well been written in 2017.”

“Until America actually gets the political will to sustain its efforts to address the history and the legacy and segregation in the country our democracy … is not guaranteed to succeed,” Dunn said. “We’re a more diverse society now.”

The Kerner Commission also criticized news coverage of the disturbances, saying “news organizations have failed to communicate to both their black and white audiences a sense of the problems America faces and the sources of potential solutions.” It also criticized the national media’s then racial makeup.

Several African-American journalists speaking at the ASNE-APME News Leadership Conference in Washington, D.C., said the media still have some of the same problems in covering issues like Black Lives Matter.

“We learn from history that we do not learn from history,” said Charlayne Hunter-Gault, an award-winning journalist who was the first African-American woman to enroll at the University of Georgia.

Harris is working on a book on the 50th anniversary of the Kerner Commission’s report, to be released in March.

“I think if we can get people to see that these problems are still with us,” Harris said, “that it’s in the interests of all of us, to do something about it.”