The Unites States’ increasing ethnic diversity will lead to whites becoming a racial minority in America before mid-century, demographers predict. Source: National Geographic

It was a long time coming, but by every measure, America’s white majority is coming to an end. What are the implications?

Last year, data released by the U.S. Census Bureau found that the non-Hispanic white population was the only group to experience more deaths than births between July 2015 and July 2016, with Asians and Latinos experiencing the most growth, and robust nonwhite population growth more than making up the difference.

While America is often called a majority white Christian nation founded for the benefit of said group, the United States is no longer dominated by that demographic. Although Christians are nearly 70 percent of all Americans, white Christians are now only 43 percent of the population, due in no small measure to immigration and declines in religious affiliation. This drop is across the board, regardless of denomination. Even white evangelicals, the core of Trump supporters, 81 percent of whom supported him at the polls, are falling in number, along with white mainline Protestants, amid white decline and an increasing Latino presence in the Catholic Church.

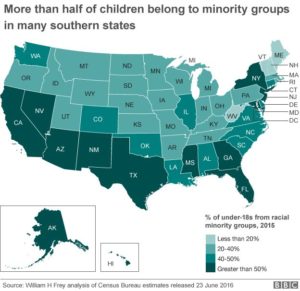

There are other indicators of the demographic shift. In 2016, for the first time, the population under age 10 became minority white — with non-metropolitan areas remaining whiter, aging and shrinking — and a number of states have become minority white, including California, Hawaii, Nevada, New Mexico and Texas. The Census Bureau reported that in 2011 a majority of babies under age 1 born in the United States were nonwhite. A majority of American children will be Black or Brown by 2020, which is already the case in the U.S. K-12 public school system. Some institutions of higher learning, such as Harvard University, have responded to the new reality by admitting its first majority nonwhite freshman class.

This reality of the inevitable white minority has many implications, in terms of political and economic power dynamics, white backlash, and policies promulgated by white nationalist politicians who attempt to emulate apartheid-era South Africa and undermine the rights and power of an emerging dark majority.

The election of Donald Trump to the highest office in the land was a primary example of a collective white meltdown — or at least among the numerical majority of whites who voted for him — an existential crisis of white supremacy and privilege in progress. “Make America Great Again” was interpreted by some as a clarion call for white-skin solidarity, a return to the pre-civil rights era days, when the dominance of white men was unquestioned, Black people were invisible to the dominant society, and relegated to the back of the bus in a literal and figurative sense.

The days for which some white people long, in which everyone around them looked like them is gone. Two surveys found that nearly 40 percent of Americans believe “newcomers threaten traditional American customs and values,” while nearly one-third of white people said “The idea of America where most people are not white bothers me.” Conservative whites placed their faith in Trump as the Great White Hope, the last chance to save white conservative Christians from the country’s demographic and cultural changes — which they viewed as American decline — in order to maintain white power and the white way of life.

This feeding of white paranoia is reflected in concrete policies such as a doubling down on “law and order,” the war on drugs and mass incarceration for Black people. Immigration policies are motivated by white supremacist desire to maintain a white-majority population in the United States, with a Muslim immigration ban, a border wall to stop undocumented Latino immigrants, and an end to President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who announced the decision by the Trump administration to repeal DACA, is a champion on the eugenicist Immigration Act of 1924. That law — which was designed by white supremacists to favor immigrants from Northern and Western Europe and keep Italians and Jews out of the country — was “good for America” according to Sessions.

In a country originally designed for the benefit of whites, a demographic transformation of America has significant policy implications from the standpoint of racial justice, economic empowerment, political power and coalition building. In an increasingly Black and Brown America, it is expected that certain red states such as North Carolina, Arizona, Georgia, and Texas, will eventually turn blue. Under the new South, where whites are heavily Republican but large numbers of Black people are returning, and Latino and Asian people are moving in, registering more nonwhite voters, women and millennials could help progressives break the white conservative hold on the former Confederacy.

Options available to white leaders to stem the rising tide of color and delay or roll back these demographic shifts include forming a perpetual one-party state through draconian voter suppression, mass deportation and incarceration, revoking 14th Amendment birthright citizenship, racial gerrymandering, and gerrymandering the U.S. Senate by returning to elections by state legislatures.

Others believe the Census Bureau statistics mislead the public about the ramifications of America’s changing demography, with progressives anticipating, as Richard Alba wrote in The American Prospect, “an inexorable change in the ethno-racial power hierarchy.” Alba argues for a more nuanced view, and believes the power of the white majority is likely to persist due to factors including the assimilation of groups such as some multiracial Americans into whiteness — a fluid concept which has changed over time — and the uncertainty of how whites will continue to maintain their diminished advantages.

The notion of Black people taking over things has been a source of white angst for centuries, whether the fear of slave rebellions in the antebellum South, efforts by the Jim Crow regime to suppress Black power and maintain the racial integrity of white people, or the conservative white reaction to the first Black president. For the first time, America is forced to consider what it means to live in a nation where white people are in the minority, and the implications for racial power dynamics, conflict and cooperation.