Each year at this time, college students return to campus, ready for new experiences. While most students’ experiences will include lectures and football games, a few unfortunate students will experience something else: sexual assault.

Unwanted sexual contact is rampant on America’s campuses. To grasp the magnitude of the problem, consider this: twenty-five percent of college women have been sexually assaulted or unwanted sexual contact on campus. Thus, at any given college, for every four female students one likely experienced a sexual assault during the pursuit of her degree.

Black women are more likely than white women to face a sexual assault during their college years. For that reason, the rollback of campus sexual assault rules announced by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos will be particularly harmful to Black women.

The Legal Framework

Although sexual assault on campus remains a serious issue, there have been attempts to address it. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits colleges that receive federal funding from discriminating on the basis of sex. Colleges were aware that Title IX required them to limit sexual assault and harassment on campus, but they were unclear about which steps to take to achieve that outcome.

In 2011, Vice President Joe Biden and Arne Duncan, secretary of education under President Obama, issued a letter that attempted to give the colleges guidance about their obligations under federal law. The letter instructed colleges that under Title IX, they were expected to: (1) distribute a notice of nondiscrimination to all students; (2) designate an individual to coordinate Title IX compliance; and (3) develop and distribute an easily understood set of policies and procedures to be followed in the event of a sexual assault.

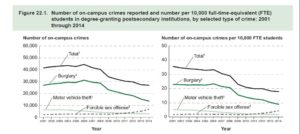

Although there is little definitive evidence, it appears that the Biden letter had a positive impact on sexual assault reporting. In the years after the letter reports of sexual assault rose, with a spike just after the letter was issued.

Source: Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2016, U.S. Dept of Education and U.S. Dept. of Justice

(Note that the reports spike after 2011, the year the Biden letter was sent.)

Unfortunately, the advances made in the past few years will soon be undone by the new education secretary. DeVos announced Thursday that she will rescind the Obama-era guidelines. While this is troubling to all students, Black female students have the most to lose when the guidelines are lost.

Black Women and Campus Assault

The data available on this issue makes it clear: Black women are at risk for sexual assault on campus. In a February 2017 study, University of Pittsburgh researchers surveyed more than 70,000 students from 120 American colleges over a two-year period. While 8.7 percent of white female respondents had been assaulted, for Black women, that number was 9.5 percent. Moreover, at least one report has noted that as compared to white women, Black women are more likely to be subjected to a physical attack or verbal threat during their assault.

Because sexual assault is highly traumatic, reporting it can be difficult. Victims of all races may feel uncomfortable reporting the crime for various reasons. Some believe it is a personal matter, some are afraid of retaliation, and some don’t believe that anything can be done. It is not surprising that rape is the most underreported crime on campus.

While all victims are reluctant to report, Black women face unique barriers when reporting their assaults. In fact, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, white women on campus are ten times more likely than Black women to report their assaults. The Chronicle gave are several reasons for the disparity. First, discussions of sexual assault often presume a white, middle-class victim, causing some nonwhite students to feel that their experiences do not matter. Students of color, especially those on campuses with racial tensions, may not feel comfortable confiding in or confronting white administrators.

Moreover, other research notes the role of racial stereotypes and conditioning. Since slavery, Black women have been portrayed as sexually promiscuous. Some Black women may avoid reporting being sexually assaulted for fear that others (regardless of race) will view the assault as proof that Black women are sexually immoral. On the other end of the spectrum, many Black women have been raised with the stereotype of the “Strong Black Woman.” Women who have been internalized this stereotype may be reluctant to report. Finally, because most rapes are committed by someone of the same race, many Black women do not report for fear that others in the Black community will accuse her of destroying a young Black man’s future.

For all of the above reasons, all women need more — not fewer — guidelines and resources on campus to combat the problems of sexual assault. DeVos’ action makes it more likely that campus rapists will get away with their crimes and potentially create more victims.

What About Black Men?

Nevertheless, some have agreed with DeVos’ action because they claim that under the Obama-era policies, many young men have been falsely accused of rape. These advocates point to the fact that the Biden letter told campuses that students could be disciplined for sexual misconduct if a school panel found that it was “more likely than not” that the student committed the assault. Further, they believe that the young men are denied due process.

While any miscarriage of justice is terrible for the accused, there are many reasons to challenge the arguments of those supporting DeVos.

While rape is severely underreported, when it is reported the report is usually substantiated. A study investing campus rape found that as little as two percent or as many as ten percent of rape claims were false. Thus, somewhere between 90 and 98 percent of rape allegations are true. Clearly, there are more young women on campus suffering in silence than there are young men being falsely accused.

However, if a young man is falsely accused, there is redress. While advocates claim that the men do not have due process, the Biden letter specifically directed schools to develop procedures for sexual assault hearings. The letter stated that the colleges were to give the accused student notice, allow him to present evidence, and allow appeals. Moreover, while the “more likely than not” standard is lower than that used in criminal proceedings, campus proceedings do not carry criminal penalties, so the use of a lower standard is reasonable.

Although some campuses may have been overzealous in the prosecution of certain cases, the fault seems to lie in the way the rules were implemented — not with the rules themselves. The answer here is not to get rid of the rules altogether, but to provide new guidance to colleges that will help them reach decisions that are fair for all parties.

The Takeaway

Sexual assault is a horrible crime. Black women who suffer through and survive this most vile of assaults deserve support. Rather than rolling back the rules that make it easier for students to report their attacks, DeVos would be wise to leave the current rules in place. Black women have enough barriers to reporting their assaults: they don’t need one of the few helpful tools to be taken away.