Source: aroundthevalleyin60days.wordpress.com

While much of the attention around symbolism in honor of the Confederacy has centered around Confederate monuments, statues and the flag itself, there are many schools across the U.S. named after Confederate leaders. The public schools are the next battlefield on continued attempts to honor the white supremacist, secessionist cause, and the people who fought to keep Black people in bondage. Sadly, over 150 years after the end of the Civil War, nearly 200 schools are named for Confederate military and administrative officials. Many Black and Latino children attend these schools that memorialize this Southern slave-owning culture yet teach them the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and economic issues. As the process to remove the slave masters, secessionists and Klan leaders from these schools begins in earnest, it is necessary to consider the impact of such indoctrination and negative imagery on the development of young minds.

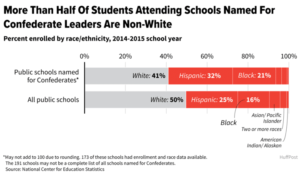

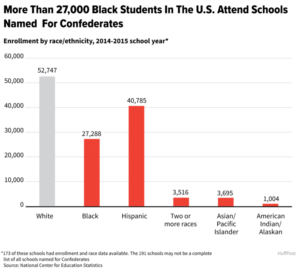

Across the country, there are 191 schools named for pro-slavery Confederate figures, according to an analysis by HuffPost based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics. More than 129,000 students attend these schools, over half of them nonwhite — 41 percent white, 32 percent Latino and 21 percent Black — including 27,000 Black students.

The debate has begun in Manassas, Virginia, where there is a move to remove the name of Confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson from the local high school. Named in 1964 during the civil rights movement, the student body is 17 percent Black, 19 percent white and more than half Hispanic. A petition is circulating in Tyler, Texas, to change the name of Robert E. Lee High. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, at least 39 schools were built after the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case, and a quarter of them have majority-Black student bodies.

In Jacksonville, Florida, where there are seven high schools named after Confederates, the district is not considering any name changes at this time. The city council president, however, has begun the process of removing Confederate monuments.

Georgia, the home of Atlanta Black Star, has eight counties named after Confederate figures. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, more than 20 schools or school districts in the Peach State are named after Confederates. For example, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Treasurer Robert Toombs and Senator Ben Hill each has a county and a school district named after him. After Virginia, Georgia has the most Confederate symbols in the United States — with 194, vs. 223 for Virginia.

Some school districts are going after Confederate symbolism, treating the Stars and Bars like a swastika. For example, the school board in Orange County, North Carolina, voted to adopt a new dress code forbidding students from wearing anything containing a Confederate flag, swastika or Ku Klux Klan logo.

The issue of racist and white supremacist symbolism in American schools is brought into focus in light of changing demographics. As of 2014, for the first time in America’s public schools, the percentage of white students fell below 50 percent—to 49.5 percent — according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Across the country, 25 percent of public school students were Latino, 16 percent were black and 5 percent were Asian or Pacific Islander, with American Indian/Alaska Native and students of two or more races comprising the remainder.

Lee Freshman High School mascot, Midland Texas (Source: Google)

“Confederate names of schools or institutions must be changed immediately. Such names make a very violent … white supremacist statement about who should have won the Civil War,” John Sims, a Black artist who has led an effort to burn and bury the Confederate flag throughout the South, told Atlanta Black Star. Sims has turned the effort into an annual event called Burn and Bury Memorial Day, a new ritual to turn the Confederate icon into a “symbol of cathartic action,” and allow for healing and transformation. “And to have black students go to such named schools and receive diplomas and certificates with these names sustains a fantasy, an historical infection that we must clear. And to begin a national healing, we must collectively understand that the Civil War is over, the Confederates lost, and the schools, streets, buildings, etc. with Confederate names must be renamed, immediately.”

Given that thousands of students still attend class in schools named for white supremacists who fought to keep Black people in bondage, this begs the question: What are students learning about the Civil War?

There is a hodgepodge of interpretations of the Civil War taught across the country, varying according to the state or even the school district. Often these decisions are decided locally. For example, in Texas, students learn that slavery was an “after issue” affecting the war. Textbooks describe slaves as “workers” and “immigrants,” while the curriculum mentions Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson as examples of “the importance of effective leadership in a constitutional republic.”

Consider also that Confederate supporters, who see the “War of Between the States” as an honorable one from the Southern point of view, have long promoted the myth that the Civil War was an issue of states’ rights — which itself is a racially loaded term — and economics rather than slavery. The result is miseducation on this decisive period in U.S. history. According to a 2011 Pew Research Center poll, 48 percent of Americans believed the Civil War was primarily about states’ rights, and 38 percent saying slavery was the main cause, and 9 percent saying both factors were equally important. The differences in responses were more racial than geographic. For example, 48 percent of whites selected states’ rights over slavery, as opposed to 39 percent of Blacks. However, 49 percent of Southern whites, and 48 percent of non-Southern whites identified states’ rights.

Edward H. Sebesta, an author and expert on the neo-Confederate movement, suggests the movement to rename the schools is a very recent phenomenon, one which African-Americans and Latinos have not entertained in the past. Sebesta — co-editor of Neo-Confederacy: A Critical Introduction (University of Texas Press) and The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader (University Press of Mississippi) — said many schools with Confederate names are predominantly Black and Latino.

“Sometime in the first half of the 1990s when I was walking out of a book store in Arlington, Texas in the parking lot was a bus from Mississippi with a basketball team unloading. They were all wearing green uniforms and what was striking was that the uniforms all had Jefferson Davis High School and the team was all African-American and Black,” Sebesta told Atlanta Black Star. “I didn’t know what to make of it, but thought that perhaps being that the team was from Mississippi there wasn’t much they could do about it and lived with it.”

In 1999, Sebesta said, the predominantly African-American Jefferson Davis Elementary School in Dallas, Texas, changed its name to Barbara Jordan Elementary School. “However, that was the exception. Even though the name of that school was changed, there wasn’t any movement or effort to change the names of Dallas schools named after Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson until 2015” he said, noting that with a few exceptions, he has not heard of any attempts to change school names until the after the Charleston Massacre in 2015.

“This is disturbing. School boards with multiple African-American and Hispanic members didn’t take any effort to change the names. Students seemed to accept these names. I don’t hear of student protests. PTAs and parent groups didn’t raise the issue either,” Sebesta added, suggesting these Confederate names were accepted as the way things were. “Generations of African-American students were educated in a built environment which unequivocally states that Black lives don’t matter and teach that lesson to them,” he said, offering that while speaking to groups for research on Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader he found that Black teachers believed the Civil War was about states’ rights.

“Recently, an NPR poll found that 44 percent of African Americans thought that Confederate monuments should stay up and 40 percent thought they should come down and 16 percent undecided,” the neo-Confederate researcher said. “Maybe the poll has some bias and you can argue a few percent, but really the percentage for should be around 5 percent because some people get confused when answering a poll,” Sebesta added. “I think it is safe to say that if there was a poll was asking Jewish people whether a Hitler highway was acceptable not only would the result be 100 percent against, Jewish groups would be mobilized to find out why that was even considered a question to ask.

“Colin Kaepernick refuses to do the Pledge of Allegiance and all hell is breaking loose with white people,” Sebesta noted. “It might be argued that changing names isn’t a priority, but that doesn’t explain the poll results.” Sebesta believes part of the problem is that for generations and up until today, U.S. history textbooks have taught a version of history in which the Confederacy is acceptable. “I recently did a review of a mainstream prestigious American history textbook, and it teaches that Black lives don’t matter. African-American students read these textbooks along with other students. The lessons seem to be learned.” In other words, the damage has been done to the psyche of Black students.