Home is where the heart is, but it is also where the health is. Last week, researchers at Princeton released a study that found that poor Black neighborhoods produce children (whether Black or not) with a higher risk of asthma than children in other neighborhoods. The study findings prove, yet again, that racism in housing markets has a negative effect on African-American health.

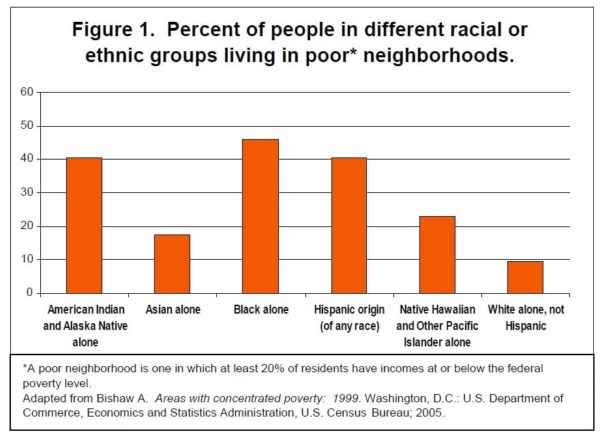

It is the environment, not race, that causes these health issues. A study of Baltimore residents found that whites living in the same neighborhoods as poor African-Americans suffered the same health problems at the same rates as their Black neighbors. However, it is rare that poor whites and Blacks live in similar conditions. Although there are more poor white people in the United States, the majority of poor whites do not live in poor neighborhoods. By contrast, poor African-Americans are concentrated in poor neighborhoods. Therefore, race is not the cause of poor health outcomes. Rather, the problem is that race and poverty combine to create neighborhoods that destroy Black health.

The Facts on Segregation

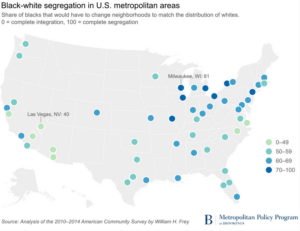

It is well known that during the Jim Crow era racially segregated neighborhoods were the norm in much of America. In 1968, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, which prohibited racial discrimination in the renting or selling of real estate. Although the Fair Housing Act made discrimination illegal, the neighborhood patterns that emerged during segregation have proven difficult to change. Beginning in the 1970s, residential segregation did decrease, particularly in the Southwest and West. Cities in the Northeast and Midwest have seen the least change. One study found that “the levels of segregation in some U.S. metropolitan areas for blacks parallel the levels of segregation in South Africa during the apartheid era.” Indeed, in many cities, sixty percent or more of the Black population would have to move to create integrated neighborhoods. So, residential segregation remains a problem in America.

Characteristics of Poor, Segregated Neighborhoods

While every neighborhood in America is unique, neighborhoods that combine racism and poverty share many of the same characteristics.

Poor, racially segregated neighborhoods lack many basic necessities. According to one study, “Political leaders have been more likely to cut spending and services in poor neighborhoods, in general, and African American neighborhoods, in particular, than in more affluent areas.” As a result, poor Black neighborhoods tend to lack parks and other greenspaces, such as dedicated trails for walking or biking. They also lack recreation centers.

In addition to the lack of municipal services, several important private businesses are missing from the neighborhoods. Poor Black neighborhoods tend to be food deserts, meaning that residents do not have ready access to supermarkets. Segregated neighborhoods have roughly three times fewer supermarkets than comparable white neighborhoods. Thus, residents must travel long distances to obtain fresh, healthy food. Even when grocery stores are located in poor, Black neighborhoods, the stores charge more money for less fresh, less healthy food.

Primary-care doctors are difficult to locate in these neighborhoods. While many of these neighborhoods have free clinics, many clinics have closed. Sadly, the remaining clinics may not have access to the latest medical equipment. Dr. Hope Landrine, PhD., director of the Center for Health Disparities at East Carolina University writes, “physicians in healthcare settings with mostly Black patients are less likely to be board certified than are those in settings for White patients.”

While these neighborhoods have too few of some things, they have too many of others. The crime rate is 29 percent higher in poor Black neighborhoods than in poor white neighborhoods in the same city. Moreover, these neighborhoods are more likely than white neighborhoods to have noise and air pollution. Segregated neighborhoods are frequently located near toxic waste sites, factories, highways, and other places that can cause health problems. For these reasons, per Dr. Landrine, “environmental exposures in [Black] neighborhoods are 5-20 times higher than those in White neighborhoods. … Segregated Black neighborhoods are characterized by higher exposures to air toxins, mercury, arsenic, sulfur dioxide, lead, and other carcinogens.”

As nearly anyone who has visited a poor Black neighborhood knows, these neighborhoods are more likely to host unhealthy products and businesses. Poor Black neighborhoods have two to three times more fast food restaurants than similar white neighborhoods. Similarly, there are more advertisements for alcohol and tobacco.

The research is clear: Racism and poverty have created neighborhoods riddled with challenges for their residents.

How Segregation Impacts Health

The racism that created these neighborhoods harms the residents in a variety of ways. Some of the effects are obvious. Polluted air that carries carcinogens clearly puts residents in segregated neighborhoods at higher risk for cancer and asthma. Surprisingly, it also increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension, and pregnancy complications such as low birth weight.

The lack of medical providers in these neighborhoods makes it harder for neighborhood residents to get health care. Moreover, because the doctors in these neighborhoods are not as well trained, health care outcomes are worse. Dr. Landrine states, “The poor health care received by segregated Blacks contributes to disparities in diabetes, hypertension, [cardiovascular disease], asthma, adult and infant mortality, quality of treatment, cancer stage at diagnosis, obesity, and health behaviors such as low cancer screening, low smoking cessation, and poor diet.”

The lack of grocery stores is also problematic. Eating fruits and vegetables reduces the risk for many conditions, including obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and some cancers. Each supermarket in a black neighborhood increases fruit and vegetable consumption for Black residents of that neighborhood by 32 percent. However, because fresh produce is not readily available in poor Black neighborhoods, neighborhood residents do not receive their benefits. Moreover, it is difficult to exercise when there is no safe place to do so. The absence of greenspace, especially when combined with higher crime rates and a neighborhood environment that may be in disrepair due to lack of funding, contributes to a lack of exercise. As Dr. Landrine notes, “Given the increased access to fast food and lower access to supermarkets and recreational facilities in segregated Black neighborhoods, it is not surprising that BMI [body mass index] increases with segregation.”

The stress associated with living in a segregated neighborhood also wears on the neighborhood residents. The behavior of Black women during pregnancy provides an example. In general, Black women smoke less than white women during pregnancy. However, Black women living in highly segregated neighborhoods smoke more during their pregnancies, and some researchers believe that the stress of living in segregated neighborhoods is a factor in the difference.

Finally, but most significantly, the houses themselves present problems. Frequently, segregated neighborhoods feature older homes. These homes, perhaps due to age, perhaps due to lack of maintenance, expose the tenants to higher rates of nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, polyvinyl chloride, and other indoor pollutants. These irritants are a factor in increased risk for asthma, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer, and pregnancy complications.

All told, as sociologists Drs. David Williams and Chiquita Collins of Harvard and Johns Hopkins wrote in their seminal work Racial Residential Segregation:A Fundamental cause of Racial Disparites in Health, “Segregation is a fundamental cause of differences in health status between African Americans and whites because it shapes socioeconomic conditions for blacks not only at the individual and household levels but also at the neighborhood and community levels.”