A Marshall Project study has found that when whites who are not police kill African-American men those homicides are ruled justifiable nearly 17 percent of the time in America, as compared with less than 2 percent for all homicides committed by non-police. Source: Getty Images

A sentiment within the Black community is that it is open season on Black men, that they are killed by police, by vigilantes with reckless abandon. One need only look at the anecdotal evidence, the cases in which white men kill Black men and evade the law because they claim self-defense, that they feared for their life and had to take matters into their own hands. A new report shows there is a statistical basis for the belief that society and the legal system do not highly regard the lives of Black men.

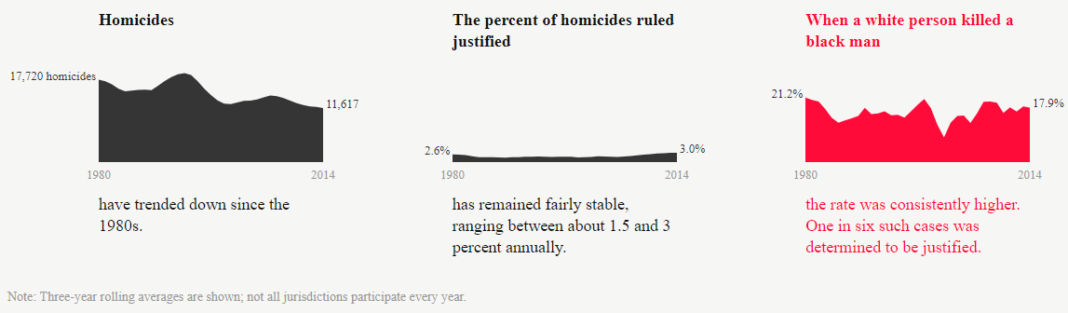

The report, released by the Marshall Project, finds that when a white person kills a Black man in the U.S., frequently that person does not face any consequences. Examining 400,000 civilian homicides between 1980 and 2014, researchers found that nearly 17 percent of homicides committed by a non-Hispanic white person against a Black man are ruled justifiable, as opposed to fewer than 2 percent of all homicides. This means that when white people kill Black men, their actions are deemed as justifiable eight times more often than other homicides. Based on FBI data, this racial analysis involving deaths in which police are not involved is the most comprehensive study of its kind.

The concept of justifiable homicide revolves around self-defense, and ultimately what is going on in the mind of the killer. “In the United States, the law of self-defense allows civilians to use deadly force in cases where they have a reasonable belief force is necessary to defend themselves or others. How that is construed varies from state to state, but the question often depends on what the killer believed when pulling the trigger,” the report said. Decisions involving self-defense are made quickly and with imperfect information, the Marshall Project noted, which means homicides are categorized as justifiable when the perpetrator did not face a real threat, yet had a “reasonable” belief the threat was real. Law enforcement, prosecutors and juries will give the killer the benefit of the doubt if that person took the life of someone who seemed dangerous.

Source: Marshall Project

Unpacking this study, it is instructive to examine some of the particular circumstances surrounding these killings and to understand how the racial disparities are at play in justifiable homicides. For example, in circumstances where a stranger was killed, 5 percent of all cases were ruled justifiable homicides, as opposed to 34 percent where a white person killed a Black man, or seven times as often. When a romantic partner was killed, 1 percent of all such homicides were justified, as opposed to 6 percent of situations where a white person took the life of a Black man — a factor of six. When a handgun was used, 3 percent of homicides were found to be justified, while in contrast, 26 percent of killings were categorized as justified when a white person killed a Black man.

Certain jurisdictions show glaring racial disparities in these justified homicides. For example, in Portland, when police investigated homicides, whites killing Black men were deemed justified twice as often as other homicides. In San Francisco, white-on-Black homicide was justified three times as often, while in New York, it was four times as often. In contrast, in Dallas, Oklahoma City, Philadelphia and Phoenix, cases of whites killing Black men were justified eight times as often, 12 times more in Houston and Los Angeles.

For the purposes of this study, who is or is not perceived as dangerous in the name of self-defense can be a color-coded proposition. Whites have an irrational fear of Black people. Implicit bias begins with preschool teachers, who perceive Black children as misbehaving and disproportionately discipline them. Racial disparities in the punishment of Black children and white children occur even when these children exhibit the same behaviors. Black children are criminalized through implicit bias, labeled violent and suspended nearly four times more often than whites, perpetuating the school-to-prison pipeline. Studies have shown that adults perceive Black girls as less innocent and more adult like that their white peers, while police assume Black boys are older, less innocent and more culpable than white boys.

When white people are armed with anti-Black racial bias and firearms, the consequences are deadly for Black people. Reports have found that police exhibit shooter bias against Black people, with blackness itself as the determining factor as to whether civilians are shot by police. White officers are trained and conditioned to perceive Black people as a greater threat, and Black men are more likely to be shot to death, even as one study showed Black men are less likely to attack police than whites who are fatally shot. In 2015, for example, while Black and Brown people accounted for about half of people killed by police, so-called racial minorities were over half of those who were unarmed when killed by police, with young Black men nine times more likely to be killed by law enforcement than any other segment of the population. Research suggests that neuroscience and psychology help explain why white officers kill Black men, with some whites not even believing they are racists, yet perceive Blacks as a threat for exhibiting certain behaviors that would not create suspicion with whites. Whites will believe Black faces are threatening because they are Black, and not due to any threatening behavior. This stereotype of Black criminality, particularly among young Black men, has significant implications for public policy and institutional racism beyond Black death, from race-based drug sentencing to the brighter employment prospects of whites with a criminal record compared to Blacks with no experience in the system.

At a time when “Stand Your Ground” laws sanction Black death at the hands of whites — and some states are motivated by the emergence of the Black Lives Matter, Dakota Access Pipeline resistance and other social justice movements to introduce legislation protecting drivers who run over and kill protesters — it becomes clear that white racial perceptions of criminality cost Black lives in very concrete ways.