ACLU

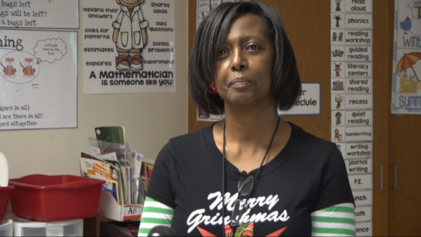

Nancy Hanks is an example of how the school-to-prison pipeline will change when teachers and educators understand their role in perpetuating the criminalization of Black children, and the power they possess to destroy that pipeline.

Now the head of elementary schools in Madison, Wisconsin, Hanks recently gave a speech at the Teach for America 25th anniversary summit. In her remarks, as the Washington Post reported, she told us everything we need to know about the unconscious bias, the decisions that educators make about the suspensions and expulsions of children, and how those decisions help to ensnare young people in the criminal justice system.

In her moving speech, Hanks recalled a time when she was a principal in a Chicago public school, and she decided to kick a boy out of school for bringing in a BB gun. Although it did not pose a threat, she expelled him anyway.

As her former student, he returned to the school, and Hanks was confronted with what she had done.

“I was angry because I had busted my behind for almost two years at that point to turn that school around, and establish community, and to repair the climate and to make kids feel safe,” she admitted. “His bringing that BB gun wasn’t just a threat to safety but a threat to me and the reputation I was building for myself and for the school. And nobody was going to compromise that.”

She could not separate the child from the act or show “just mercy” at the time, but rather went into her code of conduct, which treated toy guns, BB guns and real guns as the same, and she referred him for expulsion.

Fast forward, and the former student was returning to visit. He was attending a military academy, preparing to take the ACT and was looking for help. Hanks was “selfishly relieved” that he was thriving despite the lack of compassion she had displayed, and most of all that he had not wound up in the juvenile justice system.

The statistics she shared on Black students in the schools are compelling. According to the U.S. Department of Education in 2014, Black students represent only 16 percent of the student population across the nation, yet they constitute 32 to 42 percent of those students suspended or expelled, 27 percent of students referred to law enforcement and 31 percent of students arrested in school. But what do the numbers really mean?

“Part of our problem is when we talk about the issue of the school-to-prison pipeline, some of us are looking for someone to blame — a group, a system, an antagonist or villain to pin this issue on,” Hanks said. “We’ve somehow found a way to conveniently externalize the pipeline,” she argued. “We’ve made it about a systems and structures and vestiges, and we’ve divorced it from the actions that each of us take on a daily basis. We’ve made it this abstract thing out there somewhere, something to be shunned and examined, a Huffington Post article to share, another cause to tweet.”

She insisted that when the conversation is kept at that level, it allows educators to avoid making the issue personal and admit their own role in the pipeline.

“I know that’s hard to hear. But yes, you and I, intelligent, well-intentioned warriors of equity — we contribute to the pipeline,” Hanks said.

Faced with her moment of truth after being confronted with her former student, Hanks prayed for forgiveness and was given the opportunity to make it right when she became the chief of schools in Madison, Wisconsin. There, she has implemented a new policy based on “teaching and learning, interventions and restorative practices,” a vast departure from the district’s zero-tolerance approach.

Suspensions were eliminated in preschool through third grade, and the number of offenses eligible for expulsions and suspensions were drastically curtailed. As a result, Hanks said, suspensions decreased over 40 percent in the school district just in the first year. That translated into 1,900 restored days of instruction, of which 1,200 were for Black students.

The educational process shapes young minds, for good or for bad. Far too often, public schools provide a prison preparatory environment lacking in compassion, but replete with zero tolerance. Students of color are disciplined and regarded as aggressive and problem children, while the identical behavior of their white peers goes overlooked and unpunished. This is not just the work of white teachers, but rather the unconscious bias that all teachers possess regarding Black children.

Hanks is supported by the research. Studies have shown, for example, that Black students are disproportionately expelled and suspended, particularly in the South, and that the existence of Black children in school, not crime, determines the presence of police in a school.

A Stanford study released in April 2015 found that Black teachers are just as likely as white teachers to exhibit so-called “implicit bias”— the unconscious bias in favor of white students, and to the detriment of Black students. This implicit bias stands in marked contrast to blatant forms of racial animus and white supremacist sentiments, and plays a role in whether students are expelled and suspended, which in turn, determines whether they are more likely to face arrest or prison.

The study, published in the journal Psychological Science, is the first to connect the dots between implicit bias and school discipline, as the Huffington Post reported.

“What we have shown here is that racial disparities in discipline can occur even when black and white students behave in the same manner,” wrote authors Jason A. Okonofua and Jennifer L. Eberhardt. “Just as escalating responses to multiple infractions committed by Black students might feed racial disparities in disciplinary practices in K–12 schooling, so too might escalating responses to multiple infractions committed by black suspects feed racial disparities in the criminal-justice system,” they added.

The Stanford study involved two experiments. In the first, a racially diverse group of female teachers was screened for explicit bias. They were shown the school records of students who had misbehaved twice, and were given stereotypically Black names such as Deshawn or Darnell, or white names like Greg or Jake. After reviewing each infraction, the teachers were asked the following questions:

-

How severe was the student’s misbehavior?

-

To what extent is the student hindering you from maintaining order in your class?

-

How irritated do you feel by the student?

-

How severely should the student be disciplined?

-

Would you call the student a troublemaker?

Moving from the first infraction to the second, teachers were far more likely to increase punishment for Darnell rather than Greg.

In the second experiment, with a larger sample of teachers that also included male teachers and teachers of color, the researchers asked them to assess whether the student’s bad behavior was part of a larger pattern, and whether they would suspend the student in the future. The results were decisive: Black students were far more likely to be branded as troublemakers, and more likely to have their behavior perceived as part of a pattern and face harsh punishment.

Both samples were diverse in terms of racial makeup, and there was no notable difference in the responses.

“I think that it attests to the pervasiveness of stereotype effects,” Okonofua, told the Huffington Post. “Research has demonstrated that exposure to media influences the stereotypical associations we all make in our daily lives. Thus, all teachers, regardless of race, are more likely to think a black child, as compared to a white child, is a troublemaker.”

Okonofua suggested that in order to turn things around with implicit bias in the school setting, teachers must be capable of growth.

“Try not to think of yourself as a fixed character in the same way that you should try not to think of your students as fixed characters. Rather, think of yourself as a growing person who needs to put in effort and practice to contend with the influences of stereotypes.”