NAACP / RESTORE THE VOTES Ad Campaign Display at the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Alexandria, Va. (Courtesy: Wikimedia)

Voting is seen as one of the most sacred rights bestowed to an American citizen. That right has been challenged or taken for granted, however, to an extent that less than half of all that could vote do vote. “For the past three decades voters have been disproportionately of higher income, older or more partisan in their interests,” the voting advocacy site MassVOTE wrote. “Parallel to participation gaps are widening gaps in wealth, reduced opportunity for youth and frustration with the polarization in politics. How would our world be different if everyone participated?”

In Alabama, a recent court decision is set to affect how one of the largest groups of the voting disenfranchised may receive relief at the polls. In May, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed into a law a bill defining “moral turpitude.” Until the introduction of the bill, “moral turpitude” was a catch-all phrase that was arbitrarily applied to permanently strip ex-felons of their voting rights. Introduced after Reconstruction, “moral turpitude” and the confusion surrounding the term have been used to disenfranchise more than 250,000 Alabamans from the vote, with most being Black.

The net effect of this is fifteen percent of all Black Alabamans being denied the vote. Despite Alabama having one of the largest Black populations in the nation, a Black candidate has never been elected to a statewide office.

HB 282 restricted “moral turpitude” to the breaking of laws that grievously damages persons or the trust. This restriction effectively restored the voting rights to many ex-felons who were previously disenfranchised. Despite this, Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill – arguing that voting is a privilege, like receiving free ice cream – claimed the state has no obligation to inform these newly enfranchised ex-felons of their restored rights. In a challenge raised by the Campaign Legal Center, U.S. District Judge W. Keith Watkins ruled that the state only has the obligation to inform its county registrars.

For the 6.2 million Americans affected by voter disenfranchisement, losing the right to vote is akin to being denied American citizenship. “When they told me, I got angry,” Pastor Kenneth Glasgow, founder of the Ordinary People Society, told ThinkProgress. “I got so angry that I said okay, if I couldn’t vote, I’m gonna make sure everybody I know get their voting rights and are able to vote.”

Glasgow’s drug charges, as it turned out, were not part of the enumerated lists of “moral turpitude” crimes established by the Administrative Office of the Courts. Glasgow, like many other ex-convicts, was denied his vote even though legally he had the right.

The Suppressed Vote

Misinformation concerning ex-convicts’ voting rights is not just an Alabama problem. Per research by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, state rules on felony disenfranchisement are so varied and complicated that it is not uncommon to find election officials confused by them.

In Colorado, for example, half of the election officials the researchers spoke to did not know that parolees had the right to vote. In New York, New Jersey, and Washington State, a third of the interviewed election officials admitted that they required documentation of voting eligibility from ex-felons in order to register them to vote, despite all three states automatically restoring voting rights to ex-convicts once they have completed their prison terms.

In New York State, no such documentation requirement exists, despite election officials asking for it.

“The law in New York State is that residents may register to vote once they are off parole,” Diana Gardner Robinson, a life coach who spoke about her experiences working vote drives in non-white communities, said to Atlanta Black Star. “I encountered a number of people who had been paroled and were now off, but who had great difficulty believing that they could now register because they believed that they were disenfranchised for life.

“If this is widely believed, and given that non-whites are so over-represented in the ‘corrections’ system, it is clear that non-whites are hindered from voting by their belief, which is widely spread ‘on the street.’”

This confusion is tied into strong feelings about the issue, in which voting is not so much a constitutionally guaranteed right, but a privilege given for a productive, lawful member of society. “Society benefits from felony disenfranchisement as we as a society say two important things – voting is a sacred privilege and that when you commit certain crimes that you give up certain privileges afforded to law-abiding citizens,” Pablo Solomon, a designer and self-described futurist, told Atlanta Black Star. “It is nice that a percentage of criminals improve their lives after spending time in prison. Unfortunately, the ratio of success stories to return-to-crime stories is low. Perhaps a crime-free, productive life could lead to regaining the right to vote after x number of years?”

Felony disenfranchisement is linked to the ancient Greek and Roman concept of “civil death,” or the notion that a person ceases to exist as a member of society once he or she acts against it. Throughout history, the notion of “civil death” has played out in different ways. In the Middle Ages, “civil death” meant that no laws protected you. This means that an ex-felon then could be injured or even killed with impunity. In the Holy Roman Empire, ex-felons were declared “vogelfrei” or “free as a bird.” The term applied to not only the prisoner now being free, but to the sense that society was free of the prisoner – as a term of the release, the prisoner was banished from society.

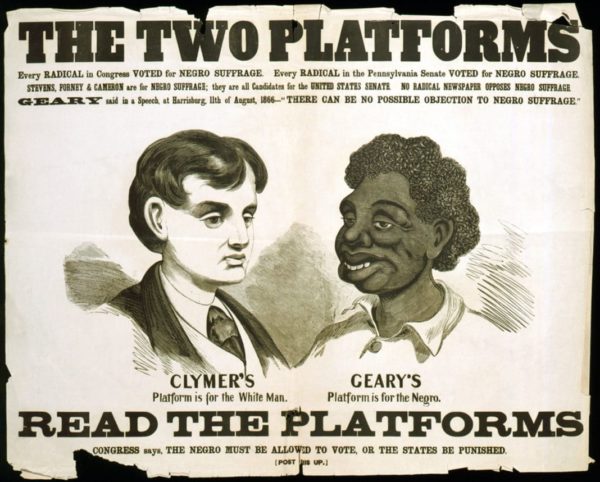

A white supremacist campaign poster from Pennsylvania, circa 1866. (Courtesy: Wikimedia)

Understanding Felony Disenfranchisement

In the United States, disenfranchisement is tied into the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which explicitly gives the states the right to deny the right to vote to any citizen due to “participation in rebellion, or other crime.” As the Constitution does not specifically spell out what type of crimes are worthy of disenfranchisements, the states themselves have set up rules that either curtailed or restored civil rights – depending on the political climate at the time.

Currently, only two states – Maine and Vermont – do not strip voting rights for committing a felony or serving a prison term. Thirteen states (Hawaii, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Utah) and the District of Columbia restore voting rights automatically after one leaves prison.

In ten states (Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, Tennessee, and Wyoming), ex-felons may lose their right to vote permanently. This is typically dependent on the severity of the crime committed. However, in the case of Florida, all ex-felons are denied the right to the vote; voting privileges can only be restored by a governor’s clemency.

“The system or persons that benefit from felony disenfranchisement are elected officials or people who run for office,” Andres A. Portela, a former congressional advisor, told Atlanta Black Star. “Felony disenfranchisement is a way to gerrymander. It allows ethnic groups who are concentrated in a particular area to not vote if they have committed a felony which begins to perpetuate a system. “

“So the way they disenfranchise a community is either by creating two different districts within a concentrated area [gerrymandering] or try to disrupt the voices that can be heard by mass incarceration. We find that with men of African American descent, there is usually a corollary effect to that demographic absent from voting. This in fact does tilt the playing field towards those who would benefit the most from it.“

Throughout American history, felony disenfranchisement has been used as a tool to silence non-whites. During post-Reconstruction, “moral turpitude” laws appeared throughout the South as a way of curtailing the Black vote. In a call to bolster the white vote against the threat of new Black voters, a new strategy of criminalizing and “civilly killing” Black voters emerged. This strategy involved marking crimes that African Americans are more likely to commit as “moral turpitude” crimes and imposing stricter prosecution of these crimes for Blacks than for whites.

“In the wake of the Civil War, states and municipalities enacted a wide range of Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws to minimize the political power of newly enfranchised African-Americans,” Angela Behrens, Christopher Uggens, and Jeff Manza wrote in their 2003 paper “Ballot Manipulation and the ‘Menace of Negro Domination’: Racial Threats and Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 1850-2002.”

“While existing scholarship has rarely addressed the origins of felon voting bans, there are extensive literatures on the origins of general disenfranchisement measures. One classical debate has concerned the social forces driving the legal disenfranchisement of African-Americans after 1890 in the South. The predominant interpretation has been that white Democrats from ‘black belt’ regions with large African-American populations led the fight for systematic disenfranchisement in the face of regional political threat.”

As the argument goes, Maine and Vermont do not have felony disenfranchisement laws because they do not have significant African American communities. To a certain extent, felony disenfranchisement’s role in gerrymandering the Black vote is unarguable: today, 38 percent of those disenfranchised from the vote are Black, constituting one out of every 13 African Americans. Felony disenfranchisement’s use as an effective gerrymandering device also means that it is unlikely to be stopped by those that could benefit from it.

The Human Cost

The untold part of felony disenfranchisement, however, is that it forces a perpetual state of sub-citizenship to those that have already completed their sentence. For those attempting to rebuild their lives after prison, this could be a crippling setback.

“Consider that ex-felons who apply for restoration of their voting rights are just that: Ex,” Alex Friedmann, associate director of the Human Rights Defense Center, wrote to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2013. Friedmann, a former convict, sued the state of Tennessee in 2008 to get his voting rights back after his application for restoration was denied. “They are not currently in prison or on parole or probation. They pay taxes but have no say in electing legislators who impose those taxes. They are subject to the same laws and rules that affect everyone, but have no political voice when those laws or rules are enacted.

“Regardless of the type of crime or how long ago it was committed, disenfranchised former offenders have no part in the election of government officials ranging from local school board members, which may directly impact their children, to the President of the United States. Instead of ‘one man, one vote,’ in many cases it’s ‘one ex-felon, no Vote’ under Tennessee’s current disenfranchisement law due to statutory requirements for payment of restitution, court costs and child support. Indeed, it seems that Tennessee’s disenfranchisement law deliberately includes economic barriers to ensure that as many impoverished ex-offenders as possible remain disenfranchised.”

Research has suggested that felony disenfranchisement – contrary to the belief that it may be a deterrent to criminal behavior – may be a direct influence on recidivism. Permanently losing the right to vote may lead an ex-felon to feel marginalized, leading to a higher rate of repeat offenses. Additionally, the argument sometimes used to justify felony disenfranchisement that ex-felons may form a voting bloc to distract or corrupt criminal law is prejudicial and suggests criminality without cause. It applies a label onto those that already have paid their debt to society.

This is becoming increasingly relevant as the United States continues to lock away more of its own citizens at a rate unmatched by any other nation. In the past 40 years, the American prison and jail population has increased 500 percent, despite the fact that the crime rate over the same period has not supported such a gain.

“When felony disenfranchisement was introduced, it was not with the intent to teaching a crime-breaker a lesson,” Nicole D. Porter, director for advocacy with the Sentencing Project, told Atlanta Black Star. “While today those that argue for felony disenfranchisement assert this view of disenfranchisement as a part of the sentence, felony disenfranchisement’s legislative history paints it as a methodology to disenfranchise Black residents from the vote. There is no punitive value in the denial of the vote.”

While some of the problems with felony disenfranchisement are institutional, such as how different agencies share information, there lies too much of an incentive to do anything to change the status quo. If voting is a constitutional right, there must be a conscious effort to protect it – for all of us.

“Despite the rhetoric, the proliferation of felony disenfranchisement is counterintuitive to the notion of criminal justice. Denying former prisoners the vote will raise the crime rate, not lower it. It will increase the sense of marginalization in these communities. It will make it harder for former criminals to acclimate. The practice has no place in an America seeking to be part of the Western World,” Porter added.