A woman at the NYC Black Lives Matter Solidarity March for Ferguson. (Courtesy: WikiMedia)

The news has been filled with stories involving hate crimes. In Aspen, Colo., for example, a homeless man was charged with pulling a knife on a Black man while repeatedly yelling racial slurs. Reports indicate the two men never met each other before and the fight centered on nunchucks the would-be assailant saw in the Black man’s pocket. In Brooklyn, a man stands indicted for punching a woman in the face while yelling homophobic slurs on the Q train. The victim was knocked unconscious and received a concussion, a broken nose and lacerations requiring eight stitches on her eye. In Portland, Ore., a man is accused of killing two and wounding one on a commuter train while screaming xenophobic rhetoric at two women dressed in hijabs.

Since the 2016 presidential election, where nationalistic fervor was stoked to help give Donald Trump the win, hate crimes have been on the rise. In the 10 days following the election, the Southern Poverty Law Center received 867 reports of hate incidents, averaging roughly 90 per day, compared to the 16 per day the FBI received from 2010 to 2015.

In nine metropolitan areas, hate crimes — or crimes in which racism, nationalism, sexism, religious intolerance or sexual-identity intolerance was the primary rationale — rose 20 percent or more in 2016. This reversed a trend many cities saw in recent years where extremist crimes declined. Washington, D.C., led the nation in the largest growth percentage at 62 percent.

What is potentially more troubling about these statistics is that they likely do not tell the whole story. According to a recent Department of Justice hate crime report, more than half of all hate crimes in the United States go unreported. Between 2011 and 2015, 42 percent of the total violent national hate crime victimizations were reported to the police, compared to 46 percent of non-hate crimes reported. Violent non-hate crimes during this period were nearly three times more likely to result in an arrest than a violent hate crime.

“The current explosion of hate crimes is fueled by a perfect storm of a number of factors, notably involving fear,” said Carole Lieberman, media psychiatrist and author of the upcoming book “LIONS and TIGERS and TERRORISTS, OH MY! How to Protect Your Child in a Time of Terror.” “There is a general sense of scarcity that causes people to be afraid that they will not get what they need — such as money, food or love. They blame this scarcity on people from other races, cultures and countries, justifying hate crimes to themselves. Today, there is an explosion in hate crimes against Muslims because people are afraid of terrorism. They do not feel that governments are doing enough to protect them, so they take things into their own hands. The perpetrators of hate crimes against Muslims are different from past perpetrators. They would not have committed hate crimes in the past, but the fear of terrorism is overwhelming.

“Some victims of hate crimes are illegal aliens, so they don’t come forward because they are afraid of being deported. Though some people would like to blame politicians for the rise in hate speech and hate crime, they are not the underlying cause.”

How Hate Crimes Are Reported Today

The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks extremism in America, collected the recollections of some of the victims of hate crimes it interviewed:

- A mother in Colorado reported, “My 12-year-old daughter is African-American. A boy approached her and said, ‘Now that Trump is president, I’m going to shoot you and all the Blacks I can find.’”

- A woman in Louisiana reported, “I was standing at a red light waiting to cross the street. A black truck with three white men pulled up to the red light. One of them yelled, ‘Fuck your Black life!’ The other two began to laugh. One began to chant ‘Trump!’ as they drove away.”

- A Washington State teacher reported, “’Build a wall’ was chanted in our cafeteria Wednesday [after the election] at lunch. ‘If you aren’t born here, pack your bags’ was shouted in my own classroom. ‘Get out, spic’ was said in our halls.”

Racism and intolerance have always been a part of the American experience. However, the election of Donald Trump, who openly used ethnically and religious inflammatory policies and rhetoric in his campaign and administration, has seemed to peel back the veil of politically correct behavior that kept such beliefs away from polite society. The rise in public xenophobia and hate-related incidents seemed to correspond with Trump’s announcement of his presidential candidacy in 2015.

According to the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting’s Hate Crime Statistics, African-Americans predominately are the likely victim of hate crimes. Of the hate crimes reported to the FBI in 2015, 30.09 percent were Black. The second-largest victim group, gay males, came in at 11.42 percent. Anti-Islamic hate crimes came in sixth of the top 10 bias motivations for hate crimes at 4.41 percent. While 40.92 percent of all reported hate crime offenses have perpetrators of an unknown race, 37.52 percent are known to be white.

While this appears to fall along traditional discriminatory fault lines, insight into the rationale behind these attacks illustrates a troubling trend. A FiveThirtyEight analysis of FBI and SPLC data shows that the leading factor that stands out as a predictor of hate incidents is income inequality. States with a higher degree of inequality are likely to have more hate incidents per capita; this conclusion holds true for data both from before and after the general election.

“It’s typically not your objective situation that makes you angry and resentful, but rather your situation relative to others you see around you,” Mark Potok, editor-in-chief of the SPLC’s journal, the Intelligence Report, said to FiveThirtyEight. “So, where income inequality is very high, so is anger and resentment against those ‘other’ people who you fear are doing better than you.”

This analysis, however, is limited based on the data available. The FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program engages in no active statistics gathering. Instead, it relies on states and independent law enforcement agencies to report hate crimes to it. This is a problem because not every state makes hate crime reports to the FBI. There is no data for Hawaii, for example, or for Mississippi, despite it having the largest per capita Black population in the nation, for 2015. Likewise, the SPLC analysis is limited to media report for its statistics; unreported incidents do not make it to their reports.

A true look at what is behind the spike in hate crimes may be impossible due to the lack of reporting. Per the FBI, 44 percent of all unreported violent hate crimes were handled by some other non-law enforcement means, such as administratively by an employer or school, through a property owner or through retaliation. Ninety percent of all reported hate crimes included some form of violence, typically, simple assault.

Based on the data available we can draw some conclusions, there is the notion that some whites feel like they are being left behind. “The current environment and political discourse contributes to the rise in hate crimes. For instance, the young lady killed in the road rage incident by a presumed 20- or 30-something white male is an example of how hate can result in the loss of life,” said Frowsa Booker-Drew, director of Community Affairs and Strategic Alliances for the State Fair of Texas and adjunct professor with the University of North Texas at Dallas. Booker-Drew is referring to the case of 18-year-old Bianca Robinson, who was shot in the head while attempting to merge at the same time as David Desper. Desper’s assault on Robinson has yet to be classified a hate crime by prosecutors as of the writing of this article.

Booker-Drew continued “She lost her life over a lane change because of some angry, self-righteous coward proving his power with a gun. This issue is multi-faceted. It is about power and that history has demonstrated the backlash that comes from Black progress. Many whites feel that they are losing power and are frustrated. Population growth from other demographics has created fear.”

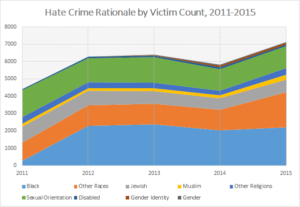

Breakdown of reported hate crimes by motivation from 2011 to 2015. Crimes against African-Americans are the leading category of hate crimes, followed by crimes against gay males. Islamophobia comes in sixth. (Courtesy: FBI Uniform Crime Reporting’s Hate Crime Statistics)

Desperation and Hate

To understand, however, how fear is fueling extremism, one has to look at some of the responses to current events. In Kentucky, for example, House Bill 14, which recognizes violent acts against police officers and first responders as hate crimes, went into effect in June. This happened while the Kentucky hate crime statute still offered no protection for crimes committed based on gender identity, ancestry, age or disability discrimination. Kentucky is the second state to enact a “Blue Lives Matter” law, following Louisiana in May 2016, and the 13th state to pass “Blue Lives Matter” legislation.

Opponents of the Kentucky law saw it as a direct response to the “Black Lives Matter” movement. While not only giving the police – who, as a class, already have special consideration under Supreme Court precedence – the same legal protected status as a nonwhite individual, the legislation also gives legitimacy to the claim that Black Lives Matter is anti-law enforcement.

As killing or attacking a police officer on duty already grants harsher penalties than killing or attacking a civilian, “Blue Lives Matter” legislation can be read as an attempt to harden police authority. For example, a police officer who feels threatened during an arrest can press hate crime charges, as well. These charges would lead to a denial of bail or bond and a heightened likeliness that a suspect may consider a plea bargain. This complicates the already existing problem of police discrimination and racial profiling.

The “Blue Lives Matter” campaign can be seen as a reflection of white fear. Formed as a result of the killings of NYPD officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, many in the “Blue Lives Matter” movement have come to blame Black Lives Matter for inciting the fervor that led to the officers’ killing. Black Lives Matter has protested injustices against Blacks in policing, housing, employment and the application of justice — most noticeably, protesting the police-related killings of unarmed Black people. However, among many whites and in conservative media, Black Lives Matter is seen as a violent, dangerous distraction that unfairly targets police.

This is relevant because, per the DOJ, 48 percent of all reported hate crimes have a racial motivation. As pointed out by Steve Chapman of the Chicago Tribune, this is nothing new. In 1965, on the eve of his March on Washington, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — the only non-president besides Jesus to have his birth commemorated as a federal holiday — carried only a 36-percent favorable rating.

“When Blacks pursue change, some whites always feel they are doing it the wrong way at the wrong pace, thus worsening race relations,” Chapman wrote. “These people believe that if Blacks gain, they will lose. And they fear that if Blacks gain more power, they will use it to exact retribution against whites.”

“The truth is that today, just as in 1966, the vast majority of Blacks don’t want to ‘get whitey.’ They just want — and demand — the same rights, opportunities and protections that whites take for granted. For some people, that’s scary enough.”