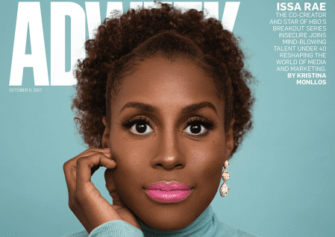

Sudanese activist Tayeb Ibrahim and his son Mohammed (AP Photo /Amr Nabil)

CAIRO (AP) — Dozens of Sudanese activists living in Egypt as refugees, many of whom fled fundamentalist Islamic militias and were close to approval for resettlement in the United States, now face legal limbo after the Supreme Court partially reinstated President Donald Trump’s travel ban on six Muslim nations, including Sudan.

Many said they are not safe in Egypt because Sudanese agents operating in the country under tacit Egyptian approval regularly threaten them and their families, sometimes targeting them with violence.

Tayeb Ibrahim, who has worked to expose Sudanese government abuses in areas it controls in the country’s volatile South Kordofan province, was partially blinded after being attacked with acid by Sudanese government agents and narrowly escaped being brought back to Sudan after being kidnapped in Egypt.

“I’m totally depressed. I was approved over a year ago for resettlement, just passed my medical exam last week and was hoping to see family living in Iowa. But instead I’ll be stuck here worried about my physical safety,” said the 40-year-old Ibrahim, who like many Sudanese refugees has no travel documents and thus cannot leave Egypt.

Sudanese living in Egypt regularly complain of discrimination and harassment, while pro-democracy rights activists and opponents of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s regime say they face abuses by both Sudanese and Egyptian security forces.

Rights groups have in the past documented cases where pro-democracy activists have been targeted by Sudanese secret police with violence, including rape. Egypt has denied any involvement in such targeted abuse.

There are officially some 36,000 Sudanese with refugee status in Egypt, most former residents of Sudan’s Darfur region who fled government-sponsored Islamic and tribal Janjaweed militias in a separatist conflict that was front-page news a decade ago but has now been eclipsed by other regional crises in Syria and Iraq.

“It’s like having our own little Islamic State group in Sudan, sponsored by the government, who has been persecuting us for years,” said Awad, a 33-year-old Sudanese women’s rights activist who has lived in Cairo since 2012. During that time, she said she has been the victim of burglaries and an attack by Sudanese men on a motorbike. Like others interviewed, she declined to give her last name out of fears for her safety.

Sudan’s Darfur region has seen violent conflict since 2003, when ethnic Africans rebelled against the Arab-dominated Sudanese government in the capital, Khartoum, accusing it of discrimination and neglect. The United Nations estimates 300,000 people have died in the conflict and some 2.7 million have fled their homes.

Al-Bashir, who rose to power in 1989, is on the International Criminal Court’s wanted list for committing crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide in Darfur. The ICC has issued two warrants for al-Bashir’s arrest, in March 2009 and July 2010.

Sudan has been under U.S. financial sanctions since the 1990s after it was designated a “state sponsor of terrorism.” But a week before leaving office, President Barack Obama eased some sanctions on Sudan citing positive actions by the government, including a reduction in offensive military activity and cooperating with the U.S. to address regional conflict and the threat of terrorism.

Later, the Trump administration singled out Sudan as one of six Muslim majority countries whose citizens were banned from immigrating to the U.S.

Activists awaiting resettlement in the U.S. say it’s unfair to punish victims of al-Bashir’s government, which has pushed for an ultraconservative interpretation of Islam and actively supported religiously inspired fighters to attack his opponents.

“We’re the victims, but we are paying the price of perpetrators,” said Basham, a 36-year-old former mechanical engineering student who said he left Sudan in 2002 after being tortured for organizing information sessions at his university about abuses in South Kordofan and working as a translator for human rights groups. He said he was selected for resettlement to the U.S. in 2016.

Awad said she has been vetted for three years by U.S. and U.N. officials and had hoped to be approved for resettlement in Kansas or Minnesota, states with large Sudanese communities.

The U.S. Embassy in Cairo declined to comment on the cases, as did the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration, which manages the vetting process. The U.S. State Department has said it would provide additional details on how the ban would affect migration “after consultation with the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security.”

Sudan’s government has at times given Cairo a green light to crack down on its opponents, while complaining at other times about mistreatment of its citizens in Egypt, depending on the political winds of the day. Lately, it has been engaged in a trade dispute with Egypt over its banning of some Egyptian agricultural products, while Cairo pressures it over links with its nemesis, the Gulf monarchy of Qatar.

Meanwhile, rights groups, including U.S.-based Human Rights Watch, say Washington should reevaluate its moves to lift sanctions on Sudan and insist certain criteria be met first, such as outlawing punishments like stoning, as well as dress code bans and official discrimination against women and girls.

Haram, a 48-year-old former teacher, who said she was arrested, raped and tortured in Sudan for collecting food and clothes for displaced people in Khartoum, has been waiting for four years for resettlement approval for herself and her five children in New York, where she has relatives.

“As a mother I’m so disappointed. I can barely provide for my children because I can only work as a maid, and besides that, there’s racism and harassment,” said Haram, who, like others with refugee status, is banned from working in Egypt.

Awad noted the irony of Trump’s travel ban: While it seeks to protect America against Islamic extremists, in the case of Sudanese in Egypt, it was punishing their victims, people still threatened by their government here.

“People have to understand, I fear for my life in this country,” she said. “It’s horrible to be so close to freedom and suddenly told you have to stay for an unknown time.”