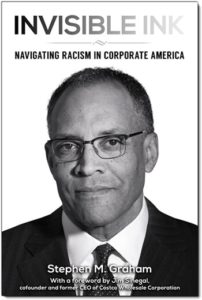

Author and attorney Stephen Graham says in his new book, “Invisible Ink: Navigating Racism in Corporate America,” that it’s past time for America to confront racism in the corporate world. (Photo/Stephen Graham)

Seattle attorney Stephen Graham, like many successful Black Americans in the corporate world, seems to have all the right credentials: an elite college education, impressive résumé and a firm handshake.

But none it likely would’ve mattered, Graham says, if he had not learned to successfully navigate the racial land mines that litter the landscape of corporate America.

Rising to the top of the corporate law ladder has been far from a walk in the park, says Graham in a recently released, self-published book about corporate racism titled “Invisible Ink: Navigating Racism in Corporate America.” The 220-page book is available in paperback on Amazon.com for $11.95.

Following his graduation from Yale Law School in 1976, Graham worked in one of Seattle’s largest law firms before becoming a corporate partner at Fenwick & West, a technology and life sciences firm for which he helped open its Seattle office.

On the outside, such achievements may contradict his argument that racial bias keeps many African-Americans from reaching their full potential in the business world. But it became clear over his long career, Graham said, that he would not be judged merely on his accomplishments like his white colleagues.

“Just start with President Obama,” said Graham, 66, who grew up in east Texas and central Iowa.

“Yes, he was elected president, but he faced significant racism throughout his presidency,” he said. “Just because we can survive cannot excuse racism. And there are those who haven’t succeeded who were not as strong as I was, but who would have succeeded but for racism.”

Of the 50,000 partners in major corporate law firms, only 1.8 percent are Black and fewer than that are equity partners, according to Graham.

Ken Chenault, CEO of American Express; Ursula Burns, former Xerox CEO and current chairwoman; and Richard Parsons, former Time Warner CEO, are among the few African-Americans who have reached the apex of business. Yet, many who have worked in corporate settings have at least one story about an experience dealing with workplace racism.

Much of the discrimination encountered in today’s business world relates to everyday, subtle acts of bias based upon stereotypes known as microagressions and unconscious bias.

In a noted 2004 study on hiring bias, Sendhil Mullainathan, an economist now at Harvard, and University of Chicago professor Marianne Bertrand sent nearly 5,000 résumés to 1,300 job ads using stereotypically white names like Emily and stereotypically Black names like Jamal. The white names received about 50 percent more callbacks than the Black names, regardless of the industry, they found.

“Ugly pockets of conscious bigotry remain in this country, but most discrimination is more insidious,” Mullainathan wrote in the New York Times.

Even some white people have been outspoken about the need to confront racial biases in business.

Jason Ford, a white entrepreneur and investor in Austin, Texas, wrote an article on Medium last November that discussed racism in corporate America. The negative responses to his challenge of confronting white privilege, he later wrote, were overwhelming.

“If my ancestors had not been white, there is a good chance I would never have been able to start a business,” Ford wrote in his original article.

Graham said what is needed to address the problem is an honest acknowledgment of bias and racism, accountability on the part of those responsible for ensuring diversity and effective ways to counter bias and a fair allocation of opportunity.

“You can’t [think] things are fine simply because you have given a Black man a job if he doesn’t receive the same pay, even if it is only one dollar less,” he said. “Over a career, it adds up.”