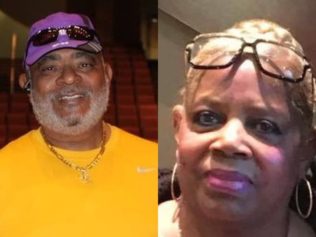

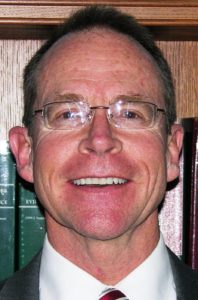

U.S. attorney Steven H. Cook of Maryville, Tenn. (Robert Wilson /Knoxville News Sentinel via AP

WASHINGTON (AP) — A zealous prosecutor who was crucial in writing the Justice Department’s new policy encouraging harsher punishments for criminals is now turning his attention to hate crimes, marijuana and the ways law enforcement seizes suspects’ cash and property.

Steve Cook’s hardline views on criminal justice were fortified as a cop on the streets of Knoxville, Tenn., in the late 1970s and early ’80s. The unabashed drug warrior is now armed with a broad mandate to review departmental policies, and observers already worried about Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ agenda are wringing their hands at Cook’s ascension.

After some 30 years of prosecuting mostly violent crimes, Cook sums up his philosophy in simple terms that crystalized one night on patrol when he came upon a family whose station wagon had been hit head-on by a “pilled-up drug user.” Two daughters were dead in the back seat. In Cook’s eyes, everyone had to be punished, including the courier who shuttled the drugs into town and the dealer who sold them to the man behind the wheel.

“This theory that we have embraced since the beginning of civilization is, when you put criminals in prison, crime goes down,” he told The Associated Press during a recent interview.

“It really is that simple.”

It is actually a widely challenged view, seen by many as far from simple. But it is one that governs Cook as he helps oversee a new Justice Department task force developing policies to fight violent crime in cities. Already he is pushing ideas that even some Republicans have dismissed as outdated and fiscally irresponsible.

Cook helped craft Sessions’ directive this month urging the nation’s federal prosecutors to seek the steepest penalties for most crime suspects, a move that will send more people to prison for longer, and which was assailed by critics as a revival of failed drug war policies that ravaged minority communities.

Former Attorney General Eric Holder, whose more lenient policies contributed to a decline in the federal prison population for the first time in decades, slammed the reversal of his work as “driven by voices who have not only been discredited but until now have been relegated to the fringes of this debate.”

Cook finds the criticism baffling. All this discussion of criminal justice changes takes the focus off the real victims, he said: drug addicts, their families and those killed and injured as the nation’s opioid epidemic rages.

“For me, it’s like the world is turned upside down,” Cook said in an interview with The Associated Press. “We now somehow see these drug traffickers as the victims. That’s just bizarre to me.”

Even some police and prosecutors supported recent bipartisan efforts to reduce some mandatory minimum sentences and give judges greater discretion in sentencing, a reversal of 1980s and ’90s-era “tough-on-crime” laws. But Cook sees today’s relatively low crime rates as a sign that those policies worked.

Long, mandatory minimum sentences can goad informants into cooperating and ensure drug peddlers stay locked up for as long as possible, he said.

As a defense attorney in 1986, Bill Killian recalled being unable to convince Cook — then a rookie prosecutor — to agree to leniency for his client, whom he described as a minor player in a massive meth lab operating in the wooded farmland of eastern Tennessee. The man had no criminal past and was not profiting like the ringleaders.

“He wanted the maximum, whatever the maximum could be,” Killian said. More than 20 years later, Killian became U.S. attorney for that region, and Cook was chief of the criminal division, overseeing mostly violent crime, gang and drug cases.

When Holder told prosecutors in 2013 that they could leave drug quantities out of charging documents, so as not to charge certain suspects with crimes that would trigger long sentences, Cook was aghast, Killian said. Killian, meanwhile, embraced Holder’s so-called smart-on-crime approach, which encouraged leniency for offenders who weren’t violent or weren’t involved in leading an organization.

Obama administration officials cited a drop in the overall number of drug prosecutions as evidence the policies were working as intended. Holder argued prosecutors were getting pickier about the cases they were bringing and said data showed they could be just as successful inducing cooperation from defendants without leveraging the threat of years-long mandatory minimum punishments.

But to Cook, there is no such thing as a low-level offender.

“Steve Cook thinks that everyone who commits a crime ought to be locked up in jail,” Killian said. “He and I have philosophical differences about that that won’t ever be reconciled.”

Now Cook is detailed to the deputy attorney general’s office in Washington, studying policies to see how they reconcile with Sessions’ top priorities: quashing illegal immigration and violence. Cook has been traveling the country alongside Sessions as he espouses his tough-on-crime agenda, seeking input from law enforcement officials that he will take to the task force as it crafts its recommendations, which are due in July.

He offers no hints about what lies ahead. But those advocating changes to the justice system are nervous. With Sessions and Cook in powerful positions, such efforts are in peril, said Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

“You’ve put the arch enemies of criminal justice reform in charge of the U.S. Justice Department, you’ve made the hill a little steep,” he said. Of Cook, he added, “He is out of central casting for old school prosecutors, and he’s nothing if not earnest. I think he is profoundly misguided, but it’s certainly not an act.”

The National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys, which Cook led before his new assignment, said his ascendancy within the Justice Department bodes well for prosecutors who felt handcuffed by Obama-era policies.

Lawrence Leiser, the group’s new president, called him inspiring.

“His heart and soul is in everything he does,” he said. “And he is a strong believer in the rule of law.”