Photo by Val Horvath/The Times/AP

On the eve of Oct. 17, 2016, 15-year-old Jaquin Thomas was found hanging in his cell at the Orleans Justice Center, an adult prison facility in New Orleans. The teen’s reported suicide came three months after entering the prison on suspicion of murder and a month after being beaten in his cell. The beating—along with claims of Thomas initially being held at the center for weeks without a court hearing, without proper medical care and without proper supervision, given the April arrest of a deputy for failing to monitor the unit where Thomas died—prompted the late teen’s family to file a wrongful death suit last week.

While troubling questions remain regarding the reported suicide, some question why any 15-year-old would be held in an adult facility in the first place.

“The Prison Rape Elimination Act makes it very clear that there’s an increased danger to children being housed in adult prisons,” says Charlotte Morrison, a senior attorney with the nonprofit, advocacy-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). She notes the 2003 act cites increased rates of sexual assault and suicide among juveniles held in adult facilities. “A child should never be housed in an adult prison and if there is some necessity to do so, there are very strict requirements,” stresses Morrison, explaining facilities not prepared for such requirements often hold “children in solitary confinement,” a “really tortuous form of confinement” that is “widely criticized and should, legally, be eliminated.”

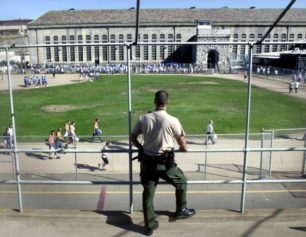

Each year, reports EJI, approximately 95,000 children are housed in America’s adult correctional facilities where they “are five times more likely to be sexually assaulted” than in juvenile facilities and “much more likely to commit suicide” than children incarcerated in juvenile facilities. Along with these inherent dangers, they “get little to no access to age-appropriate services like school, mental health and in-person family visits.” Though numerous states have laws prohibiting the incarceration of children in adult facilities, a majority do not, despite all states possessing the juvenile facilities to do so.

In 13 states, there is no minimum age for trying children as adults. And while international law prohibits sentencing children to death in prison, the United States is the only country that sentences children to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Seventy percent of those 14 or younger sentenced to life imprisonment without parole are nonwhite.

“The United States continues to be the only democracy in the world that holds on to the harshest punishments available such as the death penalty and life in prison without parole,” says Sara Totonchi, executive director of the nonprofit Southern Center for Human Rights. The fact such punishment is extended to children, continues Totonchi, is “unconscionable. It is out of step with the rest of the world, it is out of step with human rights, and we need to do the right thing and stop these practices that put us more in line with nations that are known for human rights violations.”

Morrison agrees, offering, “We are a society that is characterized by mass incarceration and we use incarceration to solve all of our social problems.” She presents how “if you’re mentally ill and poor” or “suffer from a drug addiction and are poor,” you don’t get treatment, you go to prison. And if your child has a behavior problem, continues Morrison, “we don’t have social workers in our schools” but “police offers with handcuffs. So, we just turn to the criminal justice system to solve all of our problems.”

Such punitive processes—focused largely on harsh, blanket punishment than a child’s individual issues or chance for rehabilitation—were a central component of the “super-predator” policies of the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Far removed from the premise of the juvenile justice system, which acknowledges children as developmentally different from adults and more amenable to rehabilitation, these draconian measures employed harsh “no-nonsense” sentencing and mandatory minimums to ensure first-time and nonviolent offenders were treated similar to their violent counterparts, and children, in many cases, were punished as adults.

While the impact of these extreme policies of the 1990s continues, there have been glimmers of hope along the way. In May 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Graham v. Florida that life-without-parole sentences could no longer be imposed on juveniles convicted of non-homicide offenses. Recognizing children are different from adults in important ways, the Court wrote, “Juveniles are more capable of change than adults, and their actions are less likely to be evidence of ‘irretrievably depraved character’ than are the actions of adults. It remains true that, from a moral standpoint, it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”

Some feel there is more room for optimism. “Across the country, legislatures have been passing what are known as bills to ‘raise the age,’” reports Totonchi, of current legislation in numerous states to up the threshold for juvenile crime to 18. She cites a bill in the Georgia General Assembly, HR53, which does just that. Totonchi sees such legislative measures as a “step in the right direction.”

However, while there are hopeful signs, they are of no benefit to 15-year old Jaquin Thomas, whose fate was sealed in an adult facility well before his innocence or guilt could be determined. Still, his family gleans purpose from his tragic death and its potential impact.

“It seems like he’s a sacrificial lamb,” noted Rosalind Smith-Brown at an October 25 session of the New Orleans City Council, one week after her nephew’s death. The session, attended by city leaders in criminal and juvenile justice, was largely devoted to improving communications between juvenile and adult court systems and minimizing processes that house children like Thomas in adult facilities. Though Smith-Brown knows such actions will not bring her nephew back, her message that day to City Council members and criminal justice leaders was clear:

“Think about how we go forth.”