This statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was recently removed in New Orleans, La.

Two generations of Landrieus have been mayor of the city of New Orleans, many times described as “progressive” whites, adored by many Black people and reviled as race traitors by many southern whites.

Moon Landrieu was elected in 1970 and was notorious for openly supporting Black children attending school with white kids like his own. Much like his son, Mitch, he was cursed and threatened for jeopardizing white power, obliterating white culture.

Mitch Landrieu, who in 2010 became the first elected white mayor of New Orleans in 32 years, currently enjoys sizable admiration for his management of the city’s removal of Confederate monuments. The mayor told The Washington Post the inflammatory statues weren’t built to honor Southern warriors but to double down on “the cause of white supremacy in the South” and, after the Civil War, “to send a message [of] who [is] still in control.”

The two-year journey to discard the Confederate flag and accompanying paraphernalia began in the wake of white supremacist Dylann Roof’s 2015 terrorist attack on Black worshipers in Charleston, S.C.’s Mother Emanuel AME Church. Landrieu insists that landmarks that prod whites to think and act like Roof contradict the “historic diversity” that created New Orleans.

Visiting Jonathan Capehart’s podcast, Landrieu explained that even during 2005’s catastrophic destruction of Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent levee failure, “Black people and white people didn’t see color in that moment when they had a common enemy and a common threat.” The relocation of egregious memorials will continue the rebuilding of a better New Orleans and promote racial “healing and understanding,” the mayor said.

Folly. On both accounts. Dangerous folly.

Kanye West and a chorus of millions concluded that George W. Bush and whites in power watched Black people suffer and die without care. Instead of being helped, they were branded looters and left to drown. Removing statues, like shifting furniture, is a remodeling, not the demolition, of the slave plantation.

Gary Rivlin, who found lodging in a former Louisiana slave plantation while covering the devastation of Hurricane Katrina for The New York Times, noted Landrieu’s habit of referring to the lethal storm as a moment of “racial harmony.” “Katrina: After the Flood” is Rivlin’s 2015 review of how a decade of racism, often proud and deliberate, impacted every aspect of the New Orleans rescue and rebuilding effort.

Explaining how the devastating flood was used to transform the demographics of New Orleans, Rivlin writes, “The city had a population of 455,000 before the storm, two-thirds of whom were Black; by 2010, there were 24,000 fewer whites and 118,000 fewer blacks.” Rivlin’s research suggests many whites openly discussed and wished for this racial cleansing while the city was still flooded.

“Katrina” places extra emphasis on this massive loss of Black voters, reminding readers that this forced exodus is directly related to the election of Mitch Landrieu, the first white mayor in three decades. In fact, whites flooded all New Orleans’ political offices in numbers unseen since the middle 20th century when Black citizens were restricted from voting.

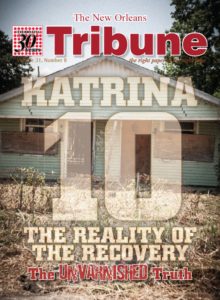

The New Orleans Tribune’s Hurricane Katrina 10-year anniversary edition.

The New Orleans Tribune, a Black-owned publication, provided exemplary coverage of the drowning and overthrow of the predominantly Black city. Their editorial, “We Got 99 Problems and Lee Circle Ain’t One,” identifies Confederate landmarks as “blatant and intentional [symbols] of racism and white supremacy,” but brilliantly explains why racist sculptures are a low-priority problem for Black people.

“Robert E. Lee didn’t steal our public schools or fire more than 7,500 mostly Black school employees or create this all-charter school system that is failing our children miserably. We know who did that … and they are not made of stone,” declares the Tribune.

New Orleans’ Black children received shoddy education before Katrina. After the flood, the classrooms were closed and the bulk of the schools were snatched from local control and placed in the Recovery School District by then-Gov. Kathleen Blanco. Thousands of Black educators lost jobs and a generation of Black children suffered immeasurable trauma while being denied a quality learning environment.

A crucial segment of Landrieu’s speech on the scrapping of the Confederate markers involved imagining how a Black parent explains to their daughter “who Robert E. Lee is and why he stands atop of our beautiful city.” The mayor asks us if General Lee inspires a Black girl to reach her maximum potential.

A substantial number of New Orleans residents submit that being told that Black people can’t be trusted to control the education of their own children does more to sabotage a Black child’s potential than any statue.

While commending Landrieu and the legions of activists who labored for years to get racist shrines toppled, The New Orleans Tribune prioritized concrete improvements to Black people’s quality of life:

“We just don’t agree with the amount of power they have attributed to these symbols, names and statues. And we do not believe that all of the time and energy that have been and will be given to this effort are well served. As such, we will reserve our work and voices for more tangible issues. And while we don’t demean those who have taken up this cause, we believe that whatever these symbols stand or stood for pales in comparison to the problems facing us today or even the ones that haunt our more recent history. Efforts to focus on them now only sidetrack us. They distract from the real plagues and blights, serious scourges — problems of the non-symbolic variety.”

When asked about the racist propaganda that depicted Black citizens fleeing Katrina as gang banging refugees, Rivlin responded, “The worst that happened were white vigilantes. Whites shooting Blacks because they didn’t want someone Black in their community.” Rivlin cites A.C. Thompson’s investigative report that uncovered nearly a dozen Black males who were killed by Whites while New Orleans was underwater.

Conversely, The Tribune described the substantial precautions taken to protect city employees and contract workers hired to remove the Confederate milestones. Noting threats of violence against people involved in carting away the statues, The Tribune reports, “One lone contractor offered a bid that, at $600,000, was more than 3.5 times the city’s budget for the statues’ removal because of security and safety risks.”

The city refuses to invest similarly in the safety and security of New Orleans’ Black residents.

—————————————————————————————————

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.