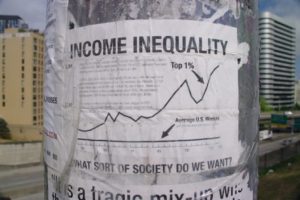

(Source: Flickr)

Much these days is said of income inequality in the U.S., of the gaping, ever-expanding chasm that separates the haves from the have nots, the rich from the poor, the 1 percent from everyone else. This, in the richest nation in the world. One author, a prominent MIT economist, has taken this discourse a step further and has concluded that America has regressed into a developing nation for most people. There is a dual economy, he states — one low-wage and the other high-income, with the former having no influence in the public policy arena and finding itself subject to the machinations of the latter.

One of the most salient points of Temin’s book is that most Americans are living under conditions found in a developing country, a Third World nation. What does this look like? For one, infrastructure for people in the U.S. low-wage economy — the crumbling roads and bridges, substandard housing and poor public transportation, for example — resembles conditions found in Latin America or Southeast Asia rather than Western Europe or Japan. Another factor that distinguishes the economy of America’s poor is the reduction of resources to the welfare state and the shredding of the social safety net. Wages are kept as low as possible to extract as much profit for the wealthy, and the poor are burdened with high debt. People also suffer from health problems, and their public education system is “hobbled by the lack of resources to make teaching an attractive career,” and in a state of crisis.

Peter Temin, Professor Emeritus of Economics at MIT (Source: MIT)

Another Third World condition found in the U.S. is the use of social control to keep the people on the lower rungs of the economic ladder from resisting the policies imposed upon them by the wealthy. Temin notes that the military, along with prisons and the Federal Reserve, are the few government activities approved by the FTE sector. Police in the U.S. have become paramilitary organizations, obtaining surplus military equipment from the Pentagon to repress Black and Latino communities. Similarly, immigration policies, particularly against Latino immigrant workers, has become militarized and reduced to border control, Temin writes, while mass incarceration, the war on drugs and tough-on-crime policies are designed to keep Black people in their place.

In his book, the MIT economist also delves into the racial dynamics of inequality, and the importance of race in discussions of inequality in the U.S. For example, he notes that whites dominate both the FTE and low-wage economies, constituting majorities in each. Blacks make up less than 15 percent of the population, which means that even if all were in the low-wage economy, they would only comprise less than one-fifth of the poor.

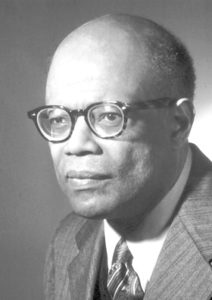

The model that Temin employs in his work is the Lewis model, developed by the late W. Arthur Lewis (1915-1991), a St. Lucian native and the first Black Nobel laureate in economics. In his pioneering work in economic development, Lewis examined how labor in a developing economy is transferred from the subsistence agricultural sector and the capitalist or industrial sector. Under Lewis’ theory, the traditional agricultural sector has surplus labor that is absorbed by the industrial sector, which leads to profits that are reinvested in the business, leading to sustained economic development and modernization.

Temin said, while the Lewis model normally is used in an optimistic way to examine economic development, he has invoked the model in a different manner. “It struck me that the Lewis model is a very good description of what is happening in the United States,” Temin said. “It struck me it was the Lewis model but run in reverse. Not that we are a failed state where law and order has broken down and people are running in the streets but a failed state because we are going back to that earlier industrial pattern that Lewis identified.” He noted the two characteristics of the model that are important in his book: One is the capitalist sector, the FTE. The FTE wants wages, earnings and living conditions in the low-wage sector as bad as possible so as to provide a cheap labor source.

W. Arthur Lewis, Nobel Laureate in Economics (Source: Wikipedia)

The other part of the equation, according to the economist, is that it is possible for individuals to move from the lower sector to the upper sector if they want to make the investment and move to the cities and get an education. “But the vast slums show it is not enough to go to the cities. You need something special to get a good job in the capitalist sector. It is the same thing here. There is a difficulty in making the transition. The FTE sector is not interested in facilitating the transition, so it becomes harder and harder. The difference between the two sectors makes it harder.”

What is missing from the discussion on inequality, Temin says, is the fact that education and salable skills —cognitive knowledge, STEM subjects and human capital — are not enough to get ahead. Rather, one also needs social capital, which speaks to how one gets along with other people, relates to others and secures jobs from others. Research has shown that Blacks who get an education have more difficulty getting jobs, Temin explains, so they wind up in lower-paying professions such as education and the nonprofit field. In contrast, people in the FTE sector have social capital, including the benefits of friends and relatives who help them. “They know people who know people who can give them jobs. They have to do the work to get promoted, but they get in the door,” Temin said. Many Black people are lacking in the social capital, the connections, to get into the FTE door. “One of the things about this is that the people who have made it, the whites who have made it, don’t recognize the role of social capital in their prosperity. A fish doesn’t know it is swimming in water, [as is the case with] people who got jobs in FTE firms,” Temin explained.

For example, he noted that sociologist Nancy DiTomaso at Rutgers University interviewed whites and discovered they have an internal narrative of their success — that they had done this all by themselves. “It said two things: One, they deserve the benefits. It’s not the community that does the benefits but the individuals, and ‘I did this, so I must be special’” he said. “Second, it makes them unsympathetic to changing things for Blacks. ‘I did this for myself and they should do this all by themselves.’” Temin does not know how to change people’s thinking and concludes it makes it hard for poor Blacks to make it up into the FTE sector, where the disproportionately few Blacks who are there are faring well.

The consequences of the dual economy are playing out in the present political environment, with politicians exploiting the economic divide for personal gain. “Since the election, we’ve had a stark example of the effects of all this inequality in the short run with Jeff Sessions in charge of the Justice Department” Temin said. “We can see a further attempt to consolidate the power of the richer group, the FTE sector and the very rich for that. And with [Betsy] DeVos being the Secretary of Education, we can see that not only will the FTE sector refuse to put money into schools of the poor Blacks but will also try to discredit the public school population in the short run for the next few years.”

The economist noted the prospects are not good for poorer African-Americans as opposed to those who “made it.” For bright, low-income kids in both the rural and urban schools, it will make it harder to escape poverty, he said.

In the longer run, however, Temin believes it is harder to predict what will happen. There could be some type of crisis, whether climate change, a war or some type of disaster.

“Once you get into one of these crises, it is hard to know how it will come out” he said. “Sometimes, it changes the power relationship and the wealth relationship.”

There are solutions to the crisis of America’s dual economy and emerging Third World conditions and Temin offers two recommendations. The first is education. “In the book, I talk about education because I thought it was something people would think about without turning over the entire system,” he said, noting efforts such as New York Mayor Bill de Blasio proposing an increase in early childhood education. Such measures are “a way of getting into the system and changing it without destabilizing it and enabling people to go from one sector to another” he said.

Another recommendation the MIT economist offers is the need to eliminate the system of mass incarceration. This is a system that, in his view, “destroys the community” and is highly problematic, as those who are sent to prison are deprived the human capital to fit in. Noting that, while America had a low state of incarceration in the 1970s, the nation has emerged with a new equilibrium —such a high degree of mass incarceration that the U.S. imprisons a higher proportion of people than other nations.

“In the 2016 campaign, there was hardly any mention about mass incarceration. The effort by Trump to deport aliens has increased mass incarceration,” Temin said. Reducing mass incarceration requires two things, he noted, both of which are very difficult. The first is to change our laws and eliminate mandatory minimum sentences and harsh penalties for minor, nonviolent offenses such as small drug possession or an expired driver’s license or registration. President Obama engaged in such reform on the federal level by reducing the penalties for crack possession vs. powder cocaine.

“The other part is to increase the funding for the judicial system so we can go back to having trials for people,” Temin added, noting that currently, nearly all people who go to jail are pressured by prosecutors to plead guilty. “The prosecutors have taken over from the judges to decide who has done the illegal activity and who is a criminal and who is not. That has become solidified in our criminal justice system, so that needs to be addressed as well.”

That is a hard sell at the moment, however, because it involves dealing with sentencing at the national level, funding of the judiciary on the state level and addressing prosecutors on a local level.