Much of L.A. burned during the riots following the Rodney King verdict.

Los Angeles, April 1992. All eyes are on the affluent suburb of Simi Valley as an all-white jury deliberates the fate of four police officers in the vicious videotaped beating of Black motorist Rodney King. Upon the repeated rendering of two simple words — “Not guilty” — the tense city of Los Angeles erupts into a five-day rebellion where 55 people die, 2,000 are injured, 3600 fires burn and property is damaged to the tune of $1 billion.

While the world will never forget the explosive events triggered by the controversial verdict of April 29, 1992, few remember the extraordinary event that took place the day before.

On April 28, a special agreement was reached. Gang members from the four major housing projects in the city’s renowned neighborhood of Watts — Hacienda Village, Imperial Courts, Jordan Downs and Nickerson Gardens — established a peace treaty to challenge police brutality, secure their communities and end years of deadly clashes that had taken far too many young lives. Given the relentless violence and high-profile status of Los Angeles’ gang culture throughout the country at the time, the Watts Gang Truce was a watershed.

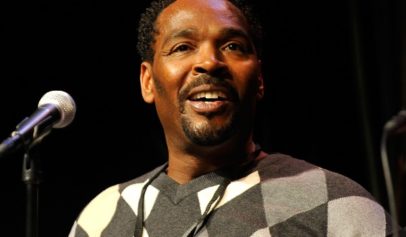

“The events that led up to the 1992 truce were very similar to what’s happening right now all across the country,” says Aqeela Sherrills, a treaty architect and co-founder of the intervention organization Amer-I-Can with legendary athlete and activist Jim Brown.

Along with other gang intervention experts, former members, activists and local residents, Sherrills will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the truce this week with a series of discussions, films and intervention events. “When we consistently complained about law enforcement’s heavy-handedness, no one believed us outside of our own community,” says Sherrills, noting several police killings in local housing projects and the community violence that brought gang members to the table.

Still, the treaty did not come together overnight. Groups including Amer-I-Can, the Nation of Islam and a few local organizations had worked toward such a pact for years, but the gangs themselves were the primary reason it happened in April of ’92. This was the early days, laughs Sherrills, and “people thought we were crazy as shi-t when we were talking about organizing a peace treaty. So, there wasn’t a lot of organizational or institutional support at all.”

The day before the verdict, Sherrills and about 200 Bloods and Crips attended a Los Angeles City Council meeting to let elected officials know of the treaty and their intention to bring other gangs into the fold to reduce the killing. “They looked at us like we were crazy and basically tried to shoo us out of there,” he recalls. “But after the verdict was read and the city started to burn, all of a sudden, we started getting all these calls from City Hall.” The city now wanted to work with the coalition to stop the violence and looting and, despite the way they were treated days earlier, the coalition agreed. We did it, says Sherrills, “not because they requested it” but, given the growing rebellion, “we didn’t want to see any of our people go to prison or be in harm’s way.” The coalition worked to stop the violence and looting until it became too dangerous to continue.

Yet, after the rebellion ceased, the coalition and truce continued for many years and some of its accomplishments still shape policy in Los Angeles today. “The first two years, in Watts, gang violence dropped 44 percent,” notes Sherrills. At the time, some city officials took note. “Any time people are willing to lay down their arms for a legitimate purpose, they should definitely be praised,” said Anthony Thomas, Mayor Richard Riordan’s liaison to South-Central, in a 1994 interview with the Los Angeles Times.

It didn’t stop there as the coalition worked with the city and police to expand the treaty to the rest of Los Angeles. The city would eventually adopt the coalition’s community-based intervention and violence-reduction strategies in the form of its LA Bridges Community Gang Prevention Program, and, later, within the Gang Reduction & Youth Development (GRYD) program still in effect today. The city leadership, says Sherrills, “met with all the interventionists, appropriated a lot of our intelligence and skill sets, and then basically claimed credit for all of our work.” Still, he clarifies, the legacy of the truce spread far beyond Los Angeles. “We went from LA to some 15 cities over the next 10 to 15 years organizing peace treaties in just about every major city across the country, causing a decrease in juvenile crime and violence nationally.” Along the way, the Watts truce would also help inspire the 1995 Million Man March.

That acknowledged, any discussion of gang truces and violence prevention would be remiss in this day and age if it didn’t address the ongoing violence in the city of Chicago. Chicago was among the cities in which Sherrills and Amer-I-Can organized a peace treaty in the mid-90s.

“One of Chicago’s biggest problems is their law enforcement,” he says, lamenting what he feels is an excessive number of “rogue cops” who, rather than preventing violence, are “invested in the problem.” And it’s not just the cops, continues Sherrills, but also the police unions who don’t adequately support their members. “These cops are experiencing traumatic stress disorder, hypervigilance and vicarious trauma from all that they witness out there. And they don’t get the proper counseling, therapy and healing modalities to help them deal with the trauma, so they are shooting, killing and robbing people themselves.”

So, what can a community do in a city where there is major corruption and little support for stopping the violence coming from City Hall?

“The community has to become public safety experts themselves by policing their own communities and being responsible for their own neighborhoods,” says Sherrills, noting this to be a part of the organizing his group has been doing across the country. “That’s essentially what has to happen.”

“You can’t have public safety without the public,” stresses Sherrills. “I think it’s a huge mistake for government not to invest more money into community-based public safety strategies.

“A huge mistake.”