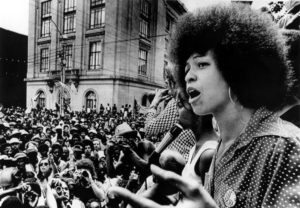

Angela Davis

Over the past decade, we have experienced a resurgence of interest in social justice as the movement for Black lives continues to grow. Black Lives Matter and other activist networks have galvanized the public around issues of anti-Black racism and the over-representation of Black and brown people in American prisons. The prison industrial complex (PIC), a vast network of American government and industry interests, incarcerates more human beings than any other nation in the world. Over 60 percent of inmates are people of color. Women are the fastest-growing population among new prisoners. One in 10 Black men in their 30s is incarcerated in the U.S.

When considering the many-layered issues that produce the conditions for mass incarceration, Angela Davis’ philosophical contributions are critical to questioning the pervasiveness of the modern prison industrial complex. Davis calls for us to decolonize our ethics about justice and question both the morality and effectiveness of punishment for crime. This is necessary work if activists are to imagine alternate futures in which justice is restorative and prisons do not exist.

Present

The ’60s were drawing to a close when Davis began organizing work around prisons. She was outraged to learn that almost 200,000 individuals in America were locked away from their families. Less than three decades later, the number of inmates in America had multiplied by 10. San Quentin, California’s first state prison, was established in 1852. It took over 100 years for California’s first nine prisons to be erected. During the 1980s alone, California’s prisons doubled, making the Reagan era one of rapid prison expansion. One could assume that more prisons were being built to address a growing domestic crime problem, but Davis astutely notes that the prison expansion project was not positively correlated with rising crime rates. In fact, prisons were multiplying during a time when crime rates had been falling. Additionally, evidence-based research continues to show that imprisonment is not the most effective method of keeping the public safe. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported that “…the overall use of imprisonment is rising throughout the world, while there is little evidence that its increasing use is improving public safety.” Despite this, the prison industry continued to grow. Today, the Prison Policy Initiative reports the total number of incarcerated human beings in the U.S. at near 2.3 million. This is staggering for a nation that contains only 5 percent of the world’s population. Still, this number is not an accurate reflection of the government’s power to detain and control people, which extends beyond the walls of federal, state and local correctional facilities. There are currently 840,000 people on parole and an additional 3.7 million individuals on probation.

When determining who goes to prison and who doesn’t, race matters. The likelihood of incarceration for Black women is 1 in 18 vs. 1 in 111 for white women. Davis argues that the prison industrial complex serves both economic and social functions. The government has allowed private corporations to contract work and services that the government used to provide. Inmates are utilized as a free labor force for companies. This surplus of able workers is taken from the margins of society — Black, brown, indigenous, poor, ill, etc. Racism, mysogynoir, homophobia, Orientalism and classism converge to funnel very vulnerable populations out of sight and out of mind. Since the primary determinants of America’s prison population are race, class and sex, people of African descent have a vested interest in building alternatives to the current structure and the eradication of the prison.

Future

By titling her book “Are Prisons Obsolete?”, Davis immediately confronts our natural attitudes toward the prison. Prisons are a social institution that, like slavery, were created, and can therefore be reformed and ultimately destroyed. Davis, an anti-prison activist, has spent much of her life’s work at the latter end of this spectrum. For most Americans, it is hard to fathom a society that does not use incarceration to punish offenders. However, beyond the current penal system are far more options for dealing with offenders than social and literal death.

Anti-prison activism considers the likelihood that attempts to reform the prison as it exists will not grasp at the roots of oppression, and that our creative efforts are better utilized in a broad approach that pulls up the oppressive fabric of the society we live in. Davis discourages us from looking to a singular institution to replace the prison structure entirely. Understanding the prison industrial complex as a network of government and private institutions, industries and agendas, activists must push for the structural changes that will relieve the causes of mass incarceration. For example, investing in education and eliminating the school-to-prison pipeline would have a tremendous effect on destabilizing the current prison system by reducing those at risk for incarceration. In addition to raising awareness about the current state of the PIC, and struggling for better conditions for the incarcerated, social justice activism is benefited by envisioning entirely new models of justice that are based on restoring community.

When dealing with such a radical, futurist project such as prison abolition, we have to address what such a vast and multi-pronged assault on this institution could look like, and what alternatives could be implemented in place of incarceration. Those who deal with the immediate issues of crime and violence in their communities and personal lives may struggle to envision how this could manifest. On one level, anti-prison activists can work on implementing strategies to reduce imprisonment systematically, such as decriminalizing non-violent offenses like drug use and sex work. On another, organizers can create structures that more efficiently deal with issues that lead to incarceration, gradually divesting our dependence on the criminal justice system. Using youth crime as an example, educators in underdeveloped schools and communities could work to ensure their schools are demilitarized. Parents and education professionals could collaborate, creating restorative justice programs within their schools as the first step to addressing problematic behaviors. These programs could function as preventative measures of diversion, providing a way for youth to resolve conflicts and receive services before potentially becoming involved with the penal system.

Individuals within communities could resist policies seeking harsher sentencing for juveniles. Truthfully, prison abolition could, and does, look like many strategies which are all important- this is part of the complex beauty of building the future.

Although the task is daunting, activists should not let the sheer enormity of the project deter them. If abolitionists had let skeptics impede their work to abolish slavery, some of the most radical liberation projects in America would have never been attempted.

Gabrielle Clark is an independent writer and community-conscious creator on a path of liberation. You can follow her @allwolfnosheep.