The Supreme Court ruled that jury deliberations are no longer private if racial bias is perceived.

If even a small amount of racial bias is perceived during “private” jury deliberations, trial judges are permitted to bypass the rule protecting the secrecy of deliberations to ensure defendants get a fair trial, the Supreme Court ruled Monday, March 6.

The divided court voted 5-to-3, allowing verdicts that are seemingly based on race or color to be thrown out — even after the verdict is delivered. The decision came during the case of Miguel Peña-Rodriguez, a Colorado man accused of sexual battery, who justices said may deserve a new trial after it was revealed that a juror made discriminatory remarks about Mexicans during deliberations.

“Racial bias implicates unique historical, constitutional and institutional concerns,” Justice Anthony Kennedy, backed by the court’s four liberal justices, wrote in his opinion. “An effort to address the most grave and serious statements of racial bias is not an effort to perfect the jury but to ensure that our legal system remains capable of coming ever closer to the promise of equal treatment under the law that is so central to a functioning democracy.”

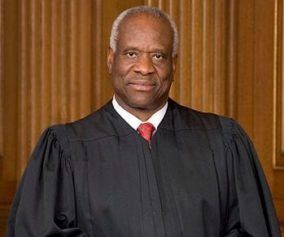

Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Clarence Thomas, objected to the ruling, arguing that jury verdicts should not be questioned once delivered, so as to protect the sanctity of the jury room.

“The court not only pries open the door, it rules that respecting the privacy of the jury room, as our legal system has done for centuries, violates the Constitution,” Justice Alito wrote. “This is a startling development, and although the court tries to limit the degree of intrusion, it is doubtful that there are principled grounds for preventing the expansion of today’s holding.”

Justice Thomas took his dissent a step further by arguing that Tuesday’s ruling violated the original understanding of the 6th and 14th Amendments, which guarantee the right to a speedy trial by an impartial jury and equal protection under the law, respectively.

“In its attempt to stimulate a ‘thoughtful, rational dialogue’ on race relations, the court today ends the political process and imposes a uniform, national rule,” the court’s only Black justice wrote. “The Constitution does not require such a rule. Neither should we.”

According to an affidavit obtained by lawyers at the permission of a trial judge, the unnamed juror in the Peña-Rodriguez case was quoted as saying that, based on his experience as a former law enforcement officer, he believed the defendant was guilty because Mexican men “believe[d] they could do whatever they wanted with women.” The juror went on to say that, “Nine times out of 10, Mexican men were guilty of being aggressive toward women and young girls,” in the area where he used to patrol.

After reviewing the affidavits, the trial judge ruled that there could be no questioning of jurors to decide whether Peña-Rodriguez deserved a new trial, as Colorado, like most states, has a law barring the court from prying into what goes on in the jury room, according to NPR. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the decision by a 4-to-3 vote, only for SCOTUS to reverse it on the basis that the “central purpose” of the 14th Amendment is to essentially guarantee equal protection under the law in order to eliminate race-based discrimination.

In their decision, justices ruled that if a juror makes any comment to indicate that he or she relied on racial bias to convict a defendant, the 6th Amendment’s promise of a speedy trial and impartial jury requires that judge’s make an exception to the rule protecting the privacy of jury deliberations. This way, the courts can ensure a defendant receives a fair trial, as guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution.

“All forms of improper bias pose challenges to the trial process. But there is a sound basis to treat racial bias with added precaution,” Justice Kennedy wrote. “A constitutional rule that racial bias in the justice system must be addressed — including, in some instances, after the verdict has been entered — is necessary to prevent a systemic loss of confidence in jury verdicts.”

Despite this win, dissenters expressed concern that permitting new trials due to race discrimination could invite a host of issues concerning gender, religion and even political party affiliation. Still, the agreeing justices ruled that the issue of race is much different from cases involving other implicit traits.