On Saturday evening, April 17, 1915, the editor of the Boston Guardian, Trotter, and a dozen or so mostly Black men and women from the Boston branch of the NAACP walked in lock step toward the city’s Tremont Theatre. They had been spurred by the arrival of the first picture show to be screened inside the White House walls, D.W. Griffith’s medium-bending film, “Birth of a Nation,” a movie Trotter found vile and detrimental to the sensibilities and progress of Negroes nationwide. Trotter and his cohorts where determined to disrupt the viewing of the movie and entered the lobby to buy tickets to the film. Stopping the viewing was part of a two-month campaign by Trotter and other Black organizations to have the film censored.

“Birth of A Nation” was adapted from the best-selling book, “The Clansman.” It was lauded by white film critics as a cinematic masterwork, pushing film at the time from a life excursion into an art form with its use of multiple cameras, close-ups, fade-away shots and sweeping battle scenes. Before Griffith, audiences would only see shots of short, funny scenes, loosely connected, if at all. Griffith envisioned telling stories by editing and weaving them into what would become the first full-length feature film in cinematic history.

“Birth of a Nation” tells a revisionist history of the American Civil War by portraying Reconstruction as a world turned upside down with Southern whites trapped under a brutal oppressive Black yoke after the freed slaves take over state government. In the film, Black lawmakers drunk on moonshine while eating fried chicken pass pro-miscegenation laws to legally get their hands on white women. The character Gus, a Black soldier from the North, with lust in his eyes, attempts to rape Flora Cameron, who jumps to her death to avoid his clutches. This inspires the Klan to hunt Gus down and lynch him as the first act in the restoration of the proper racial order of white dominance. Riding on horseback to the soundtrack of classical composer and known white supremacist Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” hundreds of KKK members come in to save the day by slaughtering and “disarming the Blacks.”

“Birth of A Nation” was the first film ever screened at the White House. The President at the time, Woodrow Wilson, famously remarked that the film was “history written with lightning.” Black leaders and viewers saw it as a perverted version of history that distorted Black characters and humanity down to stereotypes and racial pornography — a film that had to be stopped.

Monroe Trotter believed that racist ideology had to be challenged in the most daring of ways. There are lessons in the history of Trotter’s fight against the stigma of “Birth of a Nation” and his longer fight to ensure accurate, three-dimensional portrayals of Black life. He fought for progress through direct action and coupled that with principals promoting Black self-determination in all areas of life and political space. Trotter’s open fight against white supremacy took him to the White House in 1914 in a public dispute with President Wilson, protesting the segregation of the federal workplace. Wilson’s known views as a white supremacist and his sympathy for the KKK in 1915 remind the world that the current situation of having a president who openly flirts with white supremacists is not new and that many of Trotter’s strategies should be employed once again to battle against it.

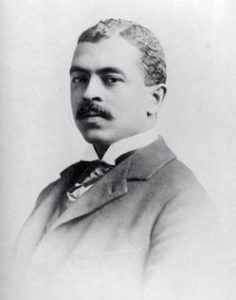

Trotter was the first member of Harvard’s Beta Phi Kappa and a contemporary to W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington, though he often took an edgier stance than both. By the time Trotter planned the Tremont demonstration, he had already earned a reputation as a firebrand, thinking the Negro race should, as his paper’s motto put it, fight “For every right, with all thy might.”

As an original attendee of the Niagra Falls Convention that laid the foundation of what would become the NAACP, Trotter didn’t become a member because, as DuBois put it in The Crisis magazine, Trotter was “suspicious of the white elements in it.”

He directly challenged Washington’s conceits to segregation and agrarian trade living in favor of equal protection under the law. Trotter objected to Washington’s ideology, which also proposed that Black folks would divorce themselves from participating in the political process or assuming leadership in the direction of their country.

Trotter would use all of his determination in the fight to stop “Birth of a Nation” from being shown. Word had gotten out to the mayor of Boston that some sort of demonstration might take place at the Tremont premiere. The mayor and police chief stationed dozens of extra officers inside the theater’s lobby, as well as hundreds of police officers outside. By 6:45 on that Saturday night, it was reported by the Boston Evening Script that as many as 125 mostly Negro men and women filled the lobby of the Tremont Theatre. After being hit by a paper matchbox, the theater manager ordered a policeman to clear the theater and allow folks who had purchased tickets previously to pick them up.

Trotter and the crowd resisted, shouting that they wanted tickets and chanted, “We want our rights!” The manager stopped all sales of tickets and Trotter assured his followers, “The police have no right to put you out.” Other leaders, including Reverend Aaron Puller, yelled, “We’ll take the law into our own hands!” Trotter added, “We’re going to stop this show.” After demanding a ticket and refusing to be removed, Trotter was sucker-punched by a plainclothes officer and arrested. Some of his followers managed to get inside the theater, with loud booing and hissing. Eggs were launched toward the screen. Thousands more Blacks gathered outside in Boston Common on Tremont Street in opposition to the film and demanded Trotter be released.

The next afternoon, following Trotter’s release, a mass meeting of 2,000 people convened on Feneuil Hall, the historic market and meeting space in Boston. News spread across the country of Trotter’s bold civil disobedience and mass mobilizations. When Trotter spoke at the rally, he aimed his line of attack on the mayor, saying, according to the Boston Herald, “If we were good enough to support you for mayor, we ought to be good enough to be protected by you from this Southern misrepresentation of our race.” The people demanded that the fight to keep the ban should continue.

By Monday, the Boston Globe reported, 1,000 demonstrators would “storm” the State House demanding the film cease screenings. Trotter lead 3,000 Black men and women through the streets of Beacon Hill singing hymns. It was a tense crowd. When one man tried to sing “America,” he was hissed and booed in favor of the better-received “We’ll hang Tom Dixon (author of “The Clansman”) to our Sour Apple Tree.” One protester’s remembrance of the moment: “I look over the vast crowd of Negro men and women and the thought came to me, ‘This is a united people … all the Black people coming together — Washington, DuBois, Trotter — forgetting their differences, 10 million Negroes would be united. A nation would really be born.”

In the end, the demonstrations did not stop the film from succeeding with white audiences at the box office. However, the type of campaigns Trotter designed would become iconic imprints in 20th-century history by showing that mass galvanization is possible. More importantly, Trotter created a blueprint for mass mobilization by Black people for civil rights that would yield some of our most important gains.