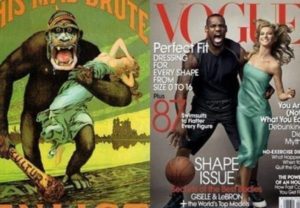

Many believe this 2008 Vogue cover of LeBron James portrays the NBA star as a raging ape.

Seventy-seven-year-old Genevieve Benjamin told the Seattle Times she cried when Barack Obama was elected president. Now that the first Black president has departed the White House, Benjamin’s “glad he’s” gone. She hopes now the Obama family can be liberated from the “ceaseless and sometimes personal attacks” by “detractors” referring to the first family as monkeys.

The racialized attacks by detractors against the Obamas started early in his tenure as president. The New York Post printed a cartoon of a rabid chimpanzee being killed by the police with the police standing over the dead animal saying, “They’ll have to find someone else to write the next stimulus bill.” The Post denied the clear racial implications of its depiction shortly after the passage of the legislation strongly supported by the president.

Detractors like former Forsyth County, Georgia, elementary schoolteacher Jane Wood Allen, who labeled First Lady Michelle Obama a “gorilla” and “a disgrace to America.” (Allen was subsequently terminated.) Mary Anne Twitty also was fired following the Department of Justice’s 2015 excoriation of the Ferguson Police Department and court system. The investigation was prompted by the 2014 killing of Michael Brown Jr. In 2011, Twitty, a former Ferguson court clerk, forwarded a photo of former president Ronald Reagan holding a baby monkey. The caption for the image read: “Rare photo of Ronald Reagan babysitting Barack Obama.”

Avoid isolating these remarks as the commentary of scattered bigots beholden to antiquated racial stereotypes. These anti-Black doctrines are core components of white culture, endorsed by the country’s founding fathers. In Notes On The State of Virginia, slaveholder and former President Thomas Jefferson suspects Black people “are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Sounding like a 19th-century version of Paladino, Jefferson equates Black people with baboons based on “the preference of the [orangutan] for the Black women over those of his own species.”

2014 MacArthur Fellow and Stanford University psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt concludes, “Referring to Blacks as apelike is among the most violent and hurtful legacies” because it justifies white power, the perpetual violation of Black people. In a 2009 Los Angeles Times essay, Eberhardt and co-author Phillip Atiba Goff deconstruct how the routine portrayal of Black people as monkeys “provided cover for slavery itself, as well as anti-Black violence,” including lynching. If Black people are no more than high-functioning chimps, anything other than white domination is a barbarous violation of the natural order.

White culture has vigorously propagated this notion for centuries. King Kong is the archetype of this white supremacist conviction. The fable of a savage, black gorilla being shackled, stolen from the jungle and brought by boat to North America for the benefit of whites is one of the most celebrated narratives of the last century. Political activist and entertainer Dick Gregory maintains this film, which was originally released in 1933, projects white hostility toward boxing legend Jack Johnson. The master pugilist was the Obama of the heavyweight division, becoming the first Black champion in 1908. Whites hated Johnson exponentially for, in their view, conquering white men in the ring and white women in the bedroom. The champion was “legally” conquered himself in 1913, sentenced to a year and a day in prison for his “immoral” conduct with white women. Apparently, enough animosity toward Johnson remains that Obama declined to issue a posthumous pardon to the wrongfully convicted prizefighter.

“Django Unchained” creator Quentin Tarantino echoes Gregory’s assessment, declaring, “Of course King Kong is a metaphor for the slave trade.” In a 2009 NPR interview, Tarantino made it plain: “‘King Kong’ is a metaphor for [whites’] fear of the Black male. And, to me, that’s obvious.” Painfully obvious, as every iteration of the film concludes with Kong’s execution.

“The Planet of the Apes” franchise – which has spawned books, films, cartoons and lunchboxes – continues the tradition, reaffirming the belief that Black people are not human. This science-fiction mythology explores an inconceivable and bestial future where talking apes rule. Importantly, the book and debut movie in this series were released in 1963 and 1968 respectively, the middle of the civil rights movement in the United States and anti-colonial efforts in Africa. In “Planet of the Apes as American Myth: Race and Politics in the Films and Television Series,” Eric Greene details how this narrative is weaponized “as shorthand for racial apocalypse and the loss of white dominance.” A world without white rule is as absurd — and horrifying — as a chatty chimp.

The Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011).

The anti-Black, dehumanizing notions of the series don’t age with time, they’re accessible and employed across multiple generations. During the ’60s, “Planet of the Apes” voiced white fear of calls for “Black Power” and the daily barrage of counter-racist marches and protests. Almost 50 years later, the sci-fi narrative is resurrected to voice white grievances with the first Black occupant of the White House. In 2010, right-wing political analyst Glenn Beck compared having Obama as president to landing on an alien world. In less than two years of Obama rule, Beck raged that his country had become “like the damn Planet of the Apes.” A subsequent 2015 event demonstrates the global acceptance of what Eberhardt describes as “historical representations of Blacks as less than human.” Rodner Figueroa, former celebrity for Univision television network, was fired after “joking” that “Michelle Obama looks like she’s from the cast of ‘Planet of the Apes.'” By conflating the Obamas with the “Apes” saga, Beck and Figueroa’s remarks each convey a timeless, white disgust with Black authority.

Author Neely Fuller Jr. insists that Black people avoid emotional responses to this predictable rhetoric. During a 2008 interview, Fuller stressed it would be better to understand that, irrespective of our bank accounts or Black accomplishments, racists are incapable of seeing Black people as anything greater than well-behaved apes. “When [a Black person] drives by in a shiny car,” Fuller insists that, to many whites, “it’s just a monkey in a car. White people built the car, put a monkey in it, trained the monkey to drive the car, so now you’re looking at a monkey in a car. This is how the white supremacists see us and they are the ones who run our business. And we have to know … when they look at us, that’s what they see.”

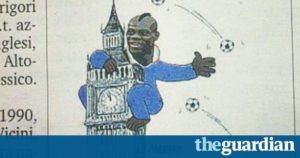

An Italian magazine depicted International soccer star Mario Balotelli as “King Kong” in 2012.

Which means, unfortunately, even with the Obamas’ departure from Washington, Genevieve Benjamin will have no reprieve from anti-Black gorilla imagery. Weeks before the inauguration of the new U.S. President, Carl Paladino, a staunch supporter of President Donald J. Trump and, more important, a standing member of the Buffalo, New York, School Board, gave this unambiguous commentary to Artvoice, a New York-based publication: “Michelle Obama. I’d like her to return to being a male and let loose in the outback of Zimbabwe where she lives comfortable in a cave with Maxie, the gorilla.”

Singer John Legend offered a powerful framework for understanding these continued depictions, as he was himself recently called a ‘monkey’ by a paparazzo while walking through JFK Airport: “Black folks have had to deal with being called monkeys for a long time and dehumanization has always been a method of racism and subjugation of Black people.”