Police officers point their weapons at demonstrators protesting the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Image courtesy of Reuters.

The city of Ferguson, Missouri went up in flames following the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Angry protesters took to the streets, demanding justice for the Black teen killed at the hands of a white cop.

Tensions boiled over as looters ransacked community businesses and rioters smashed the windows of police cars parked on the street. Images of a CVS Pharmacy burning well into the night were broadcast on news networks across the country, as the media swooped in to capture every angle of the chaos unfolding.

It was this very chaos that prompted Emory University professor Dr. Carol Anderson to write an op-ed for the Washington Post titled “Ferguson isn’t about Black rage against cops. It’s white rage against progress.”

“I’m sitting there in August 2014, and I’m at the computer but I’ve got the TV on. And the newscasters are talking about Ferguson going up in flames,” Anderson told Atlanta Black Star. “And it didn’t matter what kind of ideological stripe the newscast was on; whether it was Fox or MSNBC, or CNN, or anything in between. They were all talking about ‘Why are Black people burning up where they live?’ And it was about Black pathology; ‘What is wrong with Black people?’ ”

Liberal coverage of the Ferguson unrest focused on the anger Black folks felt concerning Brown’s death, while the conservative media chalked it up to, “Well you know, Black people burn up stuff,” the professor of African-American studies explained.

“So as they’re talking about what’s wrong with Black folk, I’m shaking my head no,” Anderson said. “We’re not looking at Black rage. What we’re really looking at is white rage. And then I went ‘Whoa.’ And then I started writing, and it just flowed.”

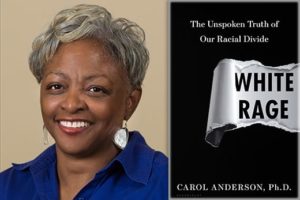

Her controversial opinion piece has since manifested into a best-selling book titled “White Rage: The Unspoken Truth About Our Racial Divide.” In it, Anderson explores the racial past and present of America, detailing how “white rage” has risen up to thwart Black advancement throughout history.

Dr. Carol Anderson, author of ‘White Rage: The Unspoke Truth of Our Racial Divide. Photo Courtesy of Emory.edu.

So what exactly is “white rage?” Anderson said it isn’t what people normally think it is – the Ku Klux Klan burning a cross in someone’s yard; images of a noose thrown over a tree limb; racial slurs being hurled at Black people, etc. Instead, she said, it’s much more subtle than that.

“White rage is – it is very cool, it is methodical,” Anderson explained. “It is the way that public policy is put into place via the legislature, via the courts, via business leaders, to undermine Black advancement, undermine African-Americans’ access to their citizenship and human rights.”

In contrast, the Emory professor goes on to explain that Black rage stems from a sense of systematic denial of justice. She asserts that the traditional levers of convincing elected leaders to do what needs to be done for the public good simply do not work.

“Black rage is a mechanism to try to bring about justice,” she said. “White rage is – you don’t see it. That’s how it works. You don’t see it.”

For example, Anderson likens white rage to the practice of gerrymandering, a process in which city, county, or state officials redraw district lines to strip Black people of their electoral power.

“It’s kind of like ‘Voila, here’s your new district,’ ” Anderson explained. “But the point is that your vote just does not count. We don’t see the laws that deal with other types of voter suppression. It’s subtle…but its impact is so destructive.”

In her book, Anderson traces similar instances of systematic racism all the way back to the beginning of the Reconstruction Era. She said this was the time when white rage really reared its ugly head, as Black folks could no longer be considered property.

“During Reconstruction, here you have Black people saying ‘I am no longer legal property, you don’t own me. I am a citizen of the United States,’ ” she explained to ABS. “To go from property to citizen? The South reared up in all kinds of wicked, malevolent, legal ways to stop that – to re-inscribe slavery by another name.”

She also chronicles the Great Migration and how white Southern officials did everything in their power to stop it.

In a chapter dedicated to the 2008 election of President Barack Obama, Anderson explores state voter suppression tactics. Among them were Florida’s cutbacks on early voting and the reduction of voting machines and poll workers in minority neighborhoods.

“Part of the way that white rage works is it uses not just levers of government but the language of democracy to mask what it’s doing,” she said. “The language we hear about protecting the integrity of the ballot box, to stop voter fraud. Who could be against that? Doesn’t that sound like protecting democracy? [But] when you look at how that policy was actually implemented, what it really does, it is a targeted hit. Particularly at those groups who voted for President Obama.”

According to Anderson, over 15 million new voters participated in the 2008 presidential election, many of whom were poor and made under $15,000 a year. Two million of those new voters were African-American, another 2 million were Hispanic, while 600,000 were Asian-American.

She goes on to cite the state of Georgia’s request for three different types of identification from persons seeking a government-issued photo ID; the picture ID is mandatory to vote. People can either show a birth certificate or passport to prove their citizenship.

“For many of the elderly, they don’t have their birth certificate,” Anderson explained. “A passport costs over a hundred dollars. Remember, many of the voters made less than $15,000 a year. How attainable is a passport with those kinds of resources? It’s not. It’s a poll tax.”

“[White rage] is this kind of ‘How did they vote?’ ” she continued. ” ‘What kinds of barriers can we put in place that make it look like this is race neutral?’ But in fact, this is very targeted.”

While Anderson received acclaim from many readers praising her for her blunt take on race in America, she also faced a lot of backlash from people deeming her book “racist” and one that simply “blames whitey for Black issues.”

Anderson said she was prepared for the negative reactions, however, because she braced herself for them. She asserts that “missed history” is often used to justify the many kinds of structural inequalities detailed in her book.

While her book may have ruffled a few feathers, the professor hopes her work will start a conversation on race in America that’s rooted in a “factually-based narrative.”

“Right now we’re really talking past each other,” she said. “And if we can start with a cohesive, factually based narrative, then I know we can move forward. But as long as we have these myths, then it makes it so hard.

“My hope is that we can begin to diffuse the power of white rage,” Anderson continued. “That we have enough folks who really want this nation to actually be what it says it is, and can be what it can be, and will work for that. That’s my hope.”