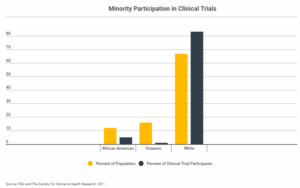

The fact remains that even as clinical trials are a means to develop new breakthrough medications and medical procedures, the process is faulty, as Undark reported. Most clinical trials leave Black people out of the process, with predominantly white subjects — especially white men — accounting for the majority of the participants. This means that without testing these drugs on a diverse group of people, they may have unknown side effects or not be as effective when used by the rest of the population.

“Differences in response to medical products have already been observed in racially and ethnically distinct subgroups of the U.S. population,” the FDA reported in 2005. “These differences may be attributable to intrinsic factors (e.g., genetics, metabolism, elimination), extrinsic factors (e.g., diet, environmental exposure, sociocultural issues), or interactions between these factors.”

For example, in the U.S., whites are more likely than Blacks and Asians to have low levels of an important enzyme that metabolizes drugs such as antidepressants, antipsychotics and beta blockers. Meanwhile, other studies have shown that Blacks do not respond well to certain types of anti-hypertensive drugs, and racial differences in skin structure can impact reactions to dermatologic and topically applied medications.

Further, according to the American Heart Association, research focusing on certain population segments such as African-Americans is crucial, given the considerable differences in the nature of heart disease across racial groups. For example, heart failure is predominantly an ischemic disease in non-Blacks (involving a restriction in blood supply), while in Blacks the disease is related to hypertension. Further, mortality rates and hospitalization for patients 45 to 64 years of age is significantly higher in Black people.

Undark

As ThinkProgress reported in 2014, non-white people in America represent only 5 percent of participants in clinical trials, while fewer than 2 percent of clinical cancer research studies focus on people of color. This comes two decades after Congress mandated that research funded by the National Institutes of Health include minorities, a study from UC Davis found. This is problematic, given that people of color are assuming more of the nation’s cancer burden, with Black people having the highest cancer rates and the shortest survival rates of anyone in the U.S. For example, although Black women are 40 percent more likely to die from breast cancer than whites, African-American women are a mere 1.3 percent of participants in cancer clinical trials.

And a 2013 FDA report found that many clinical trials excluded African- and Asian-Americans, such as Hepatitis C tests, whose participants were 83 percent white, 14 percent Black, 2 percent Asian and 2 percent Other.

But according to Undark, Tuskegee University wants to change that reality, and has partnered with Eli Lilly and Company to study African-American participation in clinical trials. Tuskegee is known for the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which poor and illiterate Black men infected with syphilis were used as human guinea pigs and allowed to go untreated between 1932 and 1972. This and other such experiments have helped engender a stigma in the Black community toward the medical community, and toward clinical trials.

Tuskegee’s new study will look exclusively at the barriers keeping Blacks from participating in clinical trials, including an unwillingness to participate due to a cautionary attitude. Rueben Warren, the director of the university’s National Bioethics Center, told Undark that a paradigm shift is necessary in the research community in order to develop policies to prove trustworthiness and develop trust.

“We’re trying to better understand why there is a lack of participation,” he said. “For years the barrier of trust has been placed on the participant.” He added, “If we can prove ourselves trustworthy [research institutions], I’m convinced that trust will be forthcoming.”

And to make that happen, Warren is working with Black organizations such as the NAACP, the African American Health Professional Organization and faith-based groups.