President Barack Obama hugs Kemba Smith during a greet with formerly incarcerated individuals who have received commutations, in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, March 30, 2016. Following that meeting the President took the group to lunch at a local restaurant. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Although President Barack Obama has taken more steps to reverse mass incarceration than any of his predecessors — he is the first one to make that move — his administration’s efforts demonstrate the bureaucratic pitfalls of dismantling the world’s largest prison system. So far it has been only a chipping away, at least when one looks at the commutation of sentences.

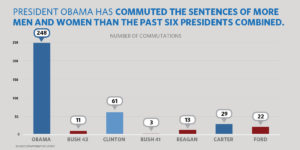

The president recently announced that he would reduce the sentences of 61 prisoners. These individuals were serving years of prison time under “outdated and unduly harsh sentencing laws” according to the White House. And as Neil Eggleston, White House Counsel, duly noted on the White House blog, “to date, the President has now commuted the sentences of 248 individuals– more than the previous six Presidents combined. And, in total, he has commuted 92 life sentences.”

Obama, unlike other presidents, has focused more on shortening the sentences of current prisoners as opposed to pardoning former prisoners. And while this administration has surpassed all others in commutations and clemency, as Dara Lind of Vox reported, it still has fallen far short of its own expectations. At one point, former Attorney General Eric Holder had surmised that toward the end of the Obama presidency, 10,000 people would have their sentences reduced.

“The power to grant pardons and commutations… embodies the basic belief in our democracy that people deserve a second chance after having made a mistake in their lives that led to a conviction under our laws,” the president said Wednesday.

For the remainder of his term, President Obama is reportedly committed to granting clemency to more people and to strengthening rehabilitation programs.

“Despite the progress we have made, it is important to remember that clemency is nearly always a tool of last resort that can help specific individuals, but does nothing to make our criminal justice system on the whole more fair and just,” Eggleston makes sure to point out. “Clemency of individual cases alone cannot fix decades of overly punitive sentencing policies. So while we continue to work to resolve as many clemency applications as possible – and make no mistake, we are working hard at this – only broader criminal justice reform can truly bring justice to the many thousands of people behind bars serving unduly harsh and outdated sentences.”

The White House

How did the Obama administration set such high expectations? Two years ago, the White House announced an effort by the Office of the Pardon Attorney to assist those who were incarcerated for low-level drug-related offenses during the height of the war on drugs, and whose sentences would have been shorter today given changes in federal law. And prisoners were encouraged to apply to the Clemency Project 2014, a pro bono project to get help with their applications. The Obama administration has received 10,000 applications, and the logjam of processing these cases has been its own fault. Meanwhile. Deborah Leff — the pardon attorney hired to oversee the applications, replacing a Bush holdover who had undermined the clemency process — resigned in January under not-so-subtle terms.

“I am unable to carry out my job effectively, despite my intense efforts to do so,” Leff wrote in her resignation letter to Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates.

“The requests of thousands of petitioners seeking justice will lie unheard,” she continued. “This is inconsistent with the mission and values to which I have dedicated my life, and inconsistent with what I believe the Department should represent.”

Leff also said she was denied “all access to the White House Counsel’s Office” impeding her ability to make final recommendations to President Obama. Further, she wrote that the Justice Department did not fulfill its commitment to provide the necessary resources to allow her to make “timely and thoughtful recommendations on clemency to the President.”

In the meantime, the analysis and commentary on what went wrong continues.

“Sixty-one grants, with over 9,000 petitions pending, is not an accomplishment to brag about,” Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota and an clemency advocate, told the Washington Post. “I know some of those still waiting, men who were grievously over-sentenced, who have reformed themselves, and never had a record of violence. My heart breaks for them, as their hope for freedom — a hope created by the members of this administration — slips away.”

According to USA Today, Leff’s departure points to a “broken and bureaucratic process” at odds with Obama’s aggressive push to issue pardons in his final months. And as The New York Times editorial board wrote, the Justice Department prevented the White House from learning about the clemency recommendations Leff had made.

Further, even as the president’s efforts are better than nothing at all, the Times said, “It is nowhere near the action needed to rectify the injustice suffered by thousands of low-level, nonviolent inmates who still languish in federal prison, serving sentences far longer than what would be imposed under today’s laws. Keeping people like this locked up for years costs not only taxpayers, but society as a whole.”

Despite this, the White House has received praise. For example, Paulette Brown — president of the American Bar Association, a partner organization in Clemency Project 2014 — expressed appreciation for the commutations, adding that “we hope to see many more commutations as the petitions submitted by Clemency Project 2014 and its army of volunteer lawyers make their way through the application process to the President’s desk.”

The Obama administration has but 10 months and thousands of backlogged applications, which are a great many. The latest announcement of 61 commutations might very well be an example of the White House playing catch up.