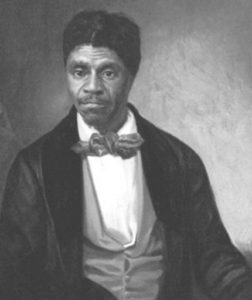

Dred Scott

1) Dred Scott, The Early Years

In 1833, Dred Scott was an enslaved African, purchased by Dr. John Emerson and moved to a base in the Wisconsin Territory. Slavery was banned in the territory pursuant to the Missouri Compromise. Thus, Scott lived there for the next four years, hiring himself out for work during the long stretches when Emerson was away. PBS.org states that Scott eventually moved to St. Louis in 1840 with his wife and Emerson.

2) The Fight

In 1846, after Emerson died, Scott sued Emerson’s widow, Eliza Sanford, to gain freedom for himself and his family, after she refused. According to African American Registry, Scott argued that he was legally free because he and his family had lived in a territory where slavery was banned.

3) Freedom

In 1850, the state court finally declared Scott free. LandmarkCases.org says that Scott’s wages had been withheld pending the resolution of his case, and during that time Eliza Sanford remarried and left her brother, John Sanford, in charge of her financial affairs, including the Scott case. Sanford, unwilling to pay the back wages owed to Scott, appealed the decision to the Missouri Supreme Court.

4) The Fight Continues

Unfortunately, the court overturned the lower court’s decision and ruled in favor of Sanford. Scott then filed another lawsuit in a federal circuit court claiming damages against Sanford’s brother, John F.A. Sanford, for Sanford’s alleged physical abuse against him. According to PBS.org, the jury ruled that Scott could not sue in federal court because he had already been deemed an enslaved African under Missouri law.

5) The Supreme Court Case

Scott appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1856. Due to a clerical error at the time, Sanford’s name was misspelled in court records, making it Sandford.

6) The Ruling

In March 1857, the court ruled in a 7-2 decision that Scott was still an enslaved African and therefore not entitled to sue in court. Scott could not be defined as free by virtue of his residency in the Wisconsin Territory, because Congress lacked the power to ban slavery in U.S. territories. African American Registry states that Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s 54-page majority opinion of the court had wide-ranging effects.

Additionally, the Supreme Court ruled that Americans of African descent, whether free or enslaved, were not American citizens and could not sue in federal court. The Court also ruled that Congress lacked power to ban slavery in the U.S. territories. Finally, the Court declared that the rights of slave-owners were constitutionally protected by the Fifth Amendment, because enslaved Africans were categorized as property.

Taney argued that free Blacks — even those who could vote in the states where they lived — could never be U.S. citizens.