It has been a full century since the start of the Great Migration of Black refugees from down South, and almost a half century since the Kerner Commission report which warned that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal.” And a new report on an old problem finds that in the city of Chicago, racial segregation remains entrenched.

The report, entitled The Impact of Racial Residential Segregation on Residence, Housing and Transportation, examines both the historic and present impact of segregation on residence, housing and transportation in the nation’s third-largest city — also the third most segregated city in the country. The study unpacks the factors and consequences related to segregation in Chicago’s most impoverished Black neighborhoods. Chicago has been in the news these days due to reports of police violence against Black people and its high crime and gun violence in Black neighborhoods. To understand the context of these ongoing issues plaguing poor, Black communities, it is incumbent upon us to understand the effects of racial segregation.

In recent years, there has been an increased national focus on “food deserts,” “employment deserts” and “transportation deserts,” in which people in vulnerable neighborhoods must travel outside of their community for basic needs such as food, to earn a livelihood or find viable transportation options. African-American neighborhoods in Chicago have been hard hit as a result of declines in the city’s manufacturing and industrial base, changes in the economy of small local businesses, and the recent closing of schools, health clinics and social service agencies. And yet, the development of new economies to replace what has been wiped out has been slow or nonexistent.

The Chicago Urban League characterizes parts of its city as “urban deserts,” where “economic disinvestment, resident displacement, population losses and the loss of community anchor institutions have, in part, resulted in community areas characterized by significant need.”

The study notes that while people associate deserts with an inability to support life, they are actually places of extreme conditions, where people must find ways to survive and adapt in a harsh environment deficient of resources.

Following the migration of Black people to the North in the past century to seek manufacturing jobs and a better life, cities such as Chicago became racially segregated by way of government policies and restrictive covenants that barred the sale or rental of property to Black people. The study has found that the patterns of segregation that were developed over the years have persisted and thrived.

Chicago Urban League

According to the report, racial residential segregation is important because of the ways in which segregation, discrimination and poverty are interrelated, including policies, practices and attitudes that create accessibility for some people and barriers to others, which preclude equal access to resources and funding that lead to good jobs, schools and a strong local economy.

“Place of residence makes it harder to get ahead, and not getting ahead makes it even harder to develop the economic and social capital that fosters residential, educational and occupational choice. This makes it harder to relocate to areas with better resources and opportunities. And on and on the cycle continues, each part reinforcing the next,” according to the study.

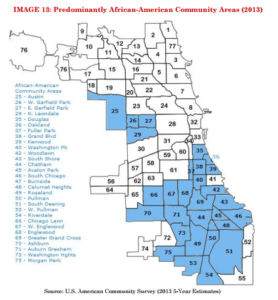

“Our findings indicate that there are 19 distinct communities in Chicago that have had little to no change in residential segregation over the past several decades, making them more vulnerable to socioeconomic burdens than other neighborhoods in Chicago,” said Stephanie Bechteler, Research and Evaluation Director at the Chicago Urban League and author of the report. “While some reports have found that people would prefer to live in more racially diverse neighborhoods, our study clearly shows that residential segregation, and the resulting impacts, remains inflexibly high in Chicago because of intentional choices over time.”

Further, affordable housing is elusive in Black Chicago communities. For example, in the depressed, predominantly African-American area of West Englewood, 75 percent of people spend at least 30 percent of their income on rent. Meanwhile, a little over half the people in Chicago as a whole spend that much on rent. Further, Black homeowners were hit hardest by the Great Recession. Between 2005 and 2013, Chicago homes lost 5 percent of their value, the report notes. However, homes in Black neighborhoods have lost 25 to 71 percent of their value.

“The findings in our report further confirm that more resources must be poured into these Black communities,” said Shari Runner, President and CEO of the Chicago Urban League. “Residential segregation is a fundamental cause of disparities from education to employment and health.”

“We look forward to sharing this compelling information with city government, relevant organizations and concerned citizens,” Runner added. “These systemic issues can no longer be ignored. The question before us should no longer be if, but how, the public and private sectors will be engaged in making investments that achieve equitable resources for all.”

Subsequent studies are expected.