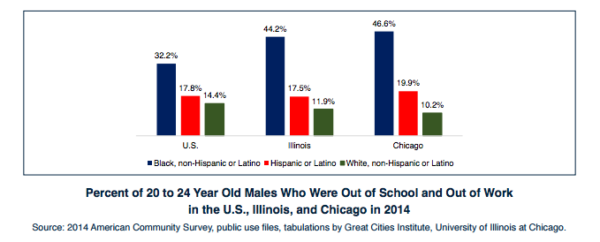

Reports from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute reveal 47 percent of Chicago’s young Black men are unemployed and not in school. Compared to young Hispanic and white men at 20 and 10 percent respectively, the striking data made for a principal discussion at the fifth annual hearing about youth joblessness hosted by the Chicago Urban League at its headquarters.

Alternative Schools Network — a nonprofit organization centered on providing economic resources to Chicago’s dissipated youth — requested the data from Chicago’s Great Cities Institute and issued a statement on the unemployment figures.

“We are seeing the results of this monumental policy failure every day, as the shootings mount up and the funerals multiply,” said Jack Wuest, executive director of the ASN. “The new data that’s being presented draws a straight line between the unemployment crisis for youth and the escalating violence in Chicago’s hardest hit neighborhoods. I’ve said it before, but it is worth repeating: Investments in creating meaningful work for these youth will pay dividends immediately and for years to come. A failure to do so has had and will continue to have dire consequences for our city and our state.”

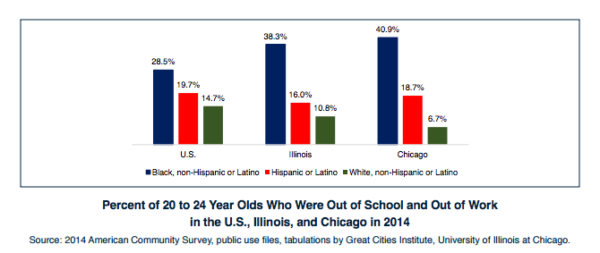

In 2014, 41 percent of Black youth in general were jobless and out of school. That is “nearly 7 percent higher than the rate in Illinois, nearly 50 percent higher than New York City, nearly 40 percent higher than Los Angeles, and nearly 44 percent higher than the U.S. rate,” the report explains.

The report also reveals the highest concentration of youth unemployment is in neighborhoods on the city’s South and West sides, such as Fuller Park, Englewood, East Garfield Park and North Lawndale, each of which are predominantly Black. The lowest concentration is in mostly white neighborhoods on the North and Northwest sides.

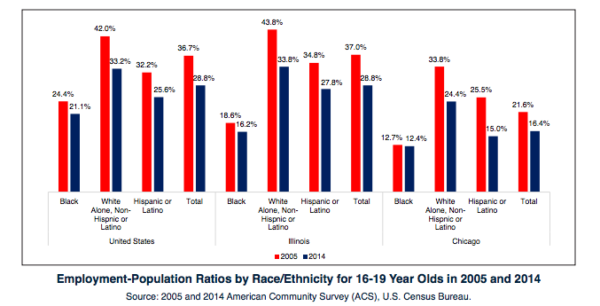

And these numbers aren’t just disappointing for young adult men. Black teenagers in Chicago, even those enrolled at school, still faced staggering unemployment rates. Some of these students need jobs to support themselves and/or their families. In 2014, 16- to 19-year-olds in Chicago, 12.4 percent of Blacks, 15.0 percent of Hispanic or Latinos, and 24.4 percent of Whites (non-Hispanic or Latinos) were employed. This, compared to the national figure of 28.8 percent, implies that youth in Chicago are less likely to be employed. Including people who are in school but don’t work, the joblessness rate is 57 percent in Chicago, compared with 51 percent nationally. More than 80 percent of 16- to 19-year-olds in Chicago are not working.

Deshawn Muldrow, 17, who lives in North Lawndale and is a senior at CCA Academy, a charter school in his neighborhood, has been struggling to find a job to raise money for college and help support his family. His mother is sick and doesn’t work, he said, so his grandmother works at a senior citizens home to support the three of them. Muldrow — who wants to study math or statistics in college — has been applying to fast-food chains and retail stores. After a few failed interviews, he is still looking.

Johnathan Allen, 24, said a walk down the street is enough to testify how joblessness pillages Black communities.

“It’s right there in your face; you don’t need statistics,” Allen said.

Combining men and women, 41 percent of Black 20- to 24-year-olds were out of work and out of school in Chicago in 2014, compared with 18.7 percent of Hispanics and 6.7 percent of whites in the same age group.

“In the process of assembling, organizing and analyzing this data, one thing became very clear to us,” Great Cities Institute Director Teresa Cordova said in a news release. “We are losing a generation of youth who have no opportunity to work in their neighborhoods. It is a tragedy for those youth and it is a tragedy for the communities they live in and the city as a whole.”

Plus jobs program, the University of Chicago Crime Lab found a 43 percent reduction in violent crime arrests for youths who secured eight-week-long part-time summer jobs with the program, compared with a control group of kids who didn’t, and the positive effect lasted 18 months after the program ended, said Kelly Hallberg, scientific director at the Crime Lab.

Wendy Bueno, 19, a high school senior who is also taking college courses, said she searched for a job for two years before becoming employed at Starbucks, thanks to a friend. Part of the delay was because she avoided working in the fast-food industry. She said even the dollar stores she applied to were looking for experience.

“How do you want us to gain experience if you don’t give us the chance?” Bueno asked.