Houston Press

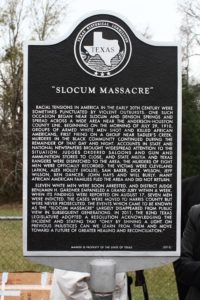

The Slocum Massacre is a part of America’s post-Civil War history that has received far less attention than it deserves, at a time when a nation’s legacy of injustice and racial violence is receiving greater attention. Although it was not as well-known as the destruction of Black Wall Street — known as the Tulsa race riot of 1921 — or the 1923 massacre in Rosewood, Florida, the Slocum Massacre was devastating nonetheless.

The slaughter which took place in the East Texas town on July 29, 1910 is now being commemorated with a historical marker that was unveiled this past weekend. And the recognition of this tragedy comes under the objection of white county leaders, according to NPR. The massacre took place when three Black teens crossed paths with a group of white men on a dirt road. The white men opened fire on the teens, and so it began. There had been reports that the Black community had planned to take revenge for the lynching of a Black man. According to initial reports, dozens of people were killed, perhaps as many as 200.

“Men were going about killing Negroes as fast as they could find them, and, so far as I was able to ascertain, without any real cause,” said Anderson County Sheriff W.H. Black, who was a white man, in the Aug. 1, 1910, edition of the New York Times. “I don’t know how many there were in the mob, but there may have been 200 or 300. They hunted the Negroes down like sheep,” wrote one reporter covering the massacre for the Washington Post at the time.

In Palestine, the county seat, state Judge B.H. Gardner ordered saloons closed and prohibited hardware stores from selling guns and ammunition, as the Washington Post reported. Calling the massacre a “disgrace,” Judge Gardner convened a grand jury a few days later. “All of you are white men, and all of you are Southern men, and it is your duty now to investigate the killing and murder of a large number of Negroes, say, at least eight and possibly 10 or 12 or more, who have been killed in the southeastern part of your county by men of your color,” Gardner said.

Nearly every resident in Slocum was subpoenaed to give testimony, and those who refused were arrested. Ultimately, seven men were indicted in 22 counts of murder, the charges dropped after Gardner ordered the cases transferred to Houston.

“In those days, the district or county attorney of Harris County felt that he could not put his time in prosecuting white men for killing Negroes in another county,” Gardner wrote. And that was the end of the story, until now.

“Eastern Texas Race War Hot and Bloody” July 31, 1910 (Page 1) (Houston Chronicle and Herald)

These events came at a time when lynchings, racial violence and so-called race riots were commonplace, as Black people following the Reconstruction era were under threat, and whites were intent upon establishing a reign of terror to keep them in their place. As the Washington Post reports, between 1885 and 1942 there were 465 recorded lynchings in Texas, of which 339 were Black victims. According to the Texas State Historical Association, this represented the third-largest number of lynchings of any state in the U.S.

“There are more than 16,000 standing historical markers in the state of Texas,” said E.R. Bills, author of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas, as reported in the Houston Press. Bills — along with Constance Hollie-Jawaid, whose great-grandfather perished in the massacre — applied to the Texas Historical Commission for the historical marker to remember the victims.

“The Slocum Massacre historical marker will apparently be the first one to specifically acknowledge racial violence against African Americans,” Bills added.

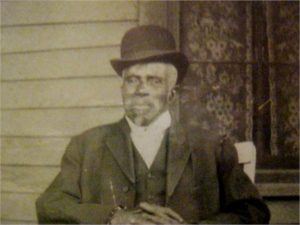

Jack Holley, one of a clan of local Slocum businessmen and farmers., and a survivor of the Slocum Massacre.

While a history of racism helped to cover up the massacre and render it all but invisible, the Texas Legislature passed a resolution in 2011 officially acknowledging that it took place. Jimmy Odom, chairman of the Anderson County Historical Commission, initially wrote to state officials: “The citizens of Slocum today had absolutely nothing to do with what happened over a hundred years ago. This is a nice, quiet community with a wonderful school system. It would be a shame to mark them as racist from now until the end of time.”

Meanwhile, there is a plan to find the mass graves from the Slocum Massacre. Bills told the Houston Press that he located one such grave on a white family’s property. When Bills told the owner he expected to find a few bodies on the land, the man reportedly responded before turning him away, “Hell no — they wouldn’t find a few bodies, they’re liable to find 50.”

“They’re still ignominiously piled on top of one another in an anonymous underground pit,” Bills said. “For this I am ashamed, because it’s folks who look just like me who perpetrate this travesty.”