Speaking at a House Judiciary committee hearing on Tuesday, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch confirmed there is no basis for the Ferguson Effect. She was responding to Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, who asked her to address the issue and said he knew of “no real evidence to substantiate this claim.”

“While certainly there may be anecdotal evidence there, as all have noted, there’s no data to support it,” Lynch said, as reported by the Guardian. “Our discussion about civil rights and the appropriate use of force and all police tactics can only serve to make all of us – community members and police officers – safer.”

A number of high-profile officials including FBI Director James Comey, Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel and U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency head Chuck Rosenberg have promoted the theory that the heightened focus on policing has made officers less aggressive. However, President Obama has rejected the idea.

“We do have to stick with the facts,” he told the International Association of Chiefs of Police. “What we can’t do is cherry-pick data or use anecdotal evidence to drive policy or to feed political agendas.”

Some conservative politicians, such as Sen. Ted Cruz and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie have taken this concept even further by criminalizing Black protest. Understanding the central role of white supremacist ideology in the Republican primary voting base, Cruz and those of his ilk have claimed the #BlackLivesMatter movement advocates for the killing of police officers. They blame President Obama and Black activists for creating an environment that supposedly places the lives of law enforcement in danger.

Cruz led a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing called, “The War on Police: How the Federal Government Undermines State and Local Law Enforcement,” as the Huffington Post reported. On Tuesday, Cruz said it was disappointing “for the federal government to treat police officers as the enemy.” However, the law enforcement officials who participated on the panel repudiated the premise, with testimony in favor of the existence of the Ferguson Effect reserved for conservative commentators and think tank spokespersons.

Ronald L. Davis, former police chief of East Palo Alto, California and now the director of the Justice Department Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, said at that hearing that the Ferguson Effect is an insult to the nation’s police officers.

“There really is no data to suggest that there is a Ferguson effect and that somehow that’s linked to any increase in crime in certain cities, because we know that there are some cities where there’s an increase, but we also know there’s some cities where there are decreases,” said Davis, who also was executive director of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. “I think we need to be very cautious … that in having this discussion, we’re not suggesting that the brave men and women who serve in law enforcement — and this is based on my 30 years — are somehow scared, which is the word I’ve heard people say, reluctant, or even suggested they’re cowards and will not do their job because they’re afraid of public scrutiny. Public scrutiny is not a negative. It’s the foundation of policing in a democratic society.”

“I have yet to see, feel or experience anything that suggests there is a ‘war on police,'” said Cedric Alexander, the police chief of DeKalb County, Georgia, in prepared testimony. “Is it a challenging issue facing America? For some it is; however, most people understand that policing is changing.”

For those who uphold the power structure and the status quo, law and order and respect for authority trumps any considerations of justice. From the beginnings of American policing, from the slave patrols of the plantation police state, the activity of Black bodies were monitored and regulated by law. Under slavery, Black people could not assemble in public, could not read or write, and were subjected to the death penalty if they engaged in rebellion.

Under Jim Crow, when the police were called upon to uphold white supremacy, the role of white supremacists was to denigrate the uppity Black folks and outside agitators who insisted on stirring up trouble and disturbing the natural order of things. So, for the racists in power, the focus was on the troublemakers causing grief, those who dared to stand up and challenge a system of oppression and the police state that undergirded the system. During the civil rights movement, J. Edgar Hoover waged a national war on Black protest with his COINTELPRO program to neutralize and eliminate Black leadership and decimate civil rights and Black nationalist groups.

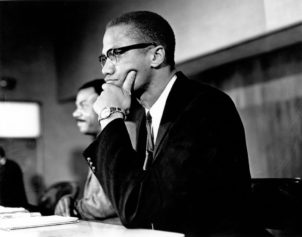

As Malcolm X said:

The press is so powerful in its image-making role, it can make the criminal look like he’s the victim and make the victim look like he’s the criminal. This is the press, an irresponsible press. It will make the criminal look like he’s the victim and make the victim look like he’s the criminal. If you aren’t careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed and loving the people who are doing the oppressing.

Meanwhile, for some, everything would be just fine if the police were allowed to play their original role, which was to mete out punishment and violence against Black people, and keep them in their place.

In their view, the outrage is the Black protest against police violence, and not the violence itself.