In the face of sexual assault accusations from over 50 women, some dating back 50 years, it’s fairly difficult to make a defense for Bill Cosby. It goes without saying that his reputation as “America’s Dad” is so marred not even the most delicious JELL-O pudding pops can save it, and mom most definitely would not approve.

Allegations and court depositions paint a picture of a man few of us would willingly let into our homes, much less into our neighborhood without an express notice that his name was on a list of registered sex offenders.

As with all tragedies, we begin to ask why and how a thing like this could happen. How could a man we all trusted turn out to be a possible rapist? And how could we have not known? Were there signs? Did we miss them? In the quest for understanding, we re-examine the past. Surely the answer is there. It must be. Hidden in the fibers of that multicolored sweater or behind that goofy grin. As we search for answers, follow the ongoing court cases, and deliberate the facts (and opinions) as we know them, we wonder not only what will become of Bill Cosby the man but of the TV show that bears his name.

The essential question many writers and media outlets have asked is: Has Bill Cosby’s behavior tainted the legacy of The Cosby Show? But few have asked the only truly essential question: Should it? Should these allegations, and yes, even the admissions by Cosby, be allowed to nullify any contribution The Cosby Show has made to Black America and America at large? Do they constitute an erasure of what, up until recently, has been viewed as a positive impact on American culture? Should we throw the baby out with the bathwater?

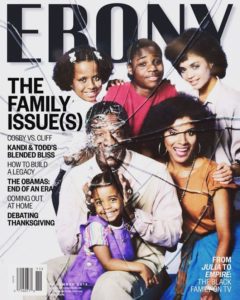

Ebony magazine in its November “Family Issue(s)” explores this topic by raising a question in a headline that says “Cliff-hanger: Can The Cosby Show Survive It? Should it?” In other words, is the show worthy of its legacy to begin with? In an excerpt from the article published on the Ebony website, there are the beginnings of an argument that almost certainly would lead readers to believe that the answer to the question is no.

Framing the piece in the context of Reagan’s war on drugs, the proliferation of gangland-style homicides, and increase in single-parents homes during the 1980s, Ebony presents to us a positive portrayal of the Black family that, for all the good feelings it engendered among Black people, did little to realistically amend the dominant public image and opinion of Black people. On the contrary, the magazine suggests that The Cosby Show corroborates the opinion that Black Americans have a problem, that Black Americans are the problem, and that the solution to the problem is simply to keep our families together in a well-educated, middle-class, nuclear unit. In short, all we have to do is play into respectability politics thereby eliminating all the trappings of poverty. The excerpt reads:

Although the show provided emotional relief from the stereotypes in the newspapers, it may have done very little to prove them false. Cosby—through Cliff Huxtable— inadvertently told America that Moynihan and Reagan were right. They contended that the ability of Black families to make economic and political gains was inextricably tied to —and hindered by—the rising rate of households led by single mothers. Both the cause and the price, they said, were illicit drug use, teenage pregnancy, academic disparities, generational poverty and incarceration. If we could just pull ourselves together and find a good (educated, middle-class) soul mate, everything would be OK.

The article and the accompanying cover image of The Huxtable family/Cosby Show cast seen through a shattered piece of glass drew support from some and criticism from the others in the Black community who were unhappy with the magazine’s decision to stir the pot.

Ebony‘s Editor-in-Chief, Kierna Mayo, addressed the controversy on Facebook. “Here’s what I’ll say: this was not an easy decision,” she wrote. “But I believe with everything that our collective healing (from this and all traumas) is tied to baring truths, confronting selves, and dismantling crutches. We aim to uplift. However, sometimes before you rise up, you break down.”

The problem with this viewpoint isn’t that there is no truth to it, but that it treats the impact of the once-great television show as an aside–a small mention only to satisfy the criteria for an objective piece. But it wasn’t a small thing. The Cosby Show was a historically groundbreaking series that depicted an educated and affluent African-American family with strong values at a time when the image of Blacks projected on the news was just the polar opposite: dumb and destitute.

The Huxtable family, led by Cliff, a doctor, and Claire, an attorney, was an aspirational mirror in which Black people could see their potential, their hopes, and their dreams reflected back at them, not simply a projection of what white society wanted them to be. The show was a clear and encouraging voice in the barrage of angry, condescending, and accusatory voices berating us and converging on the Black spirit and psyche at that time.

Not to mention the real-life challenges of poverty, drug abuse, and violence that many Black Americans knew up close and personal from which The Cosby Show provided an escape.

Black people have long counted on the resilience of our spirit to persevere through adversity. If our spirits can be broken, so can we. In slavery, we had our songs. We had spirituals that nourished our souls, instilled hope, and fostered a togetherness that kept us going. Without that means of escape, we could be broken.

That is not to say that a television sitcom could be comparable to a spiritual during slavery but instead to underscore the importance of having that “emotional relief” and those “good feelings” that The Cosby Show gave us. An importance so easily diminished in arguments that, at the heart, were made to reconcile the image of Bill Cosby with the betrayal we felt when accusations of rape came flooding in.

On a grander scale, The Cosby Show crossed color lines into the homes of white Americans who could see an alternate representation of the Black family week after week–a family that could not only be their socio-economic equal but even their betters. More importantly, they could see a family that they could relate to regardless of the color of their skin.

The Cosby Show’s impact is wide-reaching and measurable. It is credited as a significant influence for several popular sitcoms–white or black–that came after it like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Home Improvement.

At its peak, it was the most watched television series in America for five straight seasons, a feat accomplished without compromising the Blackness of its characters. The Huxtables venerated the artwork of Black artists like Ellis Wilson and Synthia Saint James on their walls, celebrated jazz music, a genre originated from the African-American culture, and expressed themselves with every bit of attitude that undoubtedly seasons many a Black household.

The show encouraged pride in Black culture and exploration of the arts. In the initial years following The Cosby Show‘s end, The National Endowment for the Arts found that 25% of original art purchases were made by African-Americans.

The impact of The Cosby Show cannot and should not be discounted because of Cosby’s purported actions. An inundation of criticism and condemnation from a white-dominated media and white-dominated Hollywood should not sway us to turn our backs on a historical and influential monument in Black television or the man who created it. This, especially, while men like Roman Polanski, convicted of sexual assault on a child, and Woody Allen, accused of the same for over 20 years, have been defended by big name celebrities and remain lauded for their filmic genius.

These men are almost untarnished in the minds of their supporters who seem to feel sorry for them while Cosby is being seared on the fire of public opinion, the ashes of his contributions to American culture blown away in the wind of America’s fury.

This is not to excuse Cosby’s behavior or dismiss the rape accusations, but as a community we should not allow others to hold our people, stories, and history to a standard they would not hold themselves.

The sting of betrayal by a man we held as an example of Black exemplary behavior should not lead us to retroactively dismantle The Cosby Show as though it were some caustic force eating away at the Black community from the start. It is all too convenient to do this as some have done in an attempt to make sense of Cosby’s misconduct or justify the metaphorical lashing the show’s legacy has received.

Realistically, if we allowed the personal lives of the writers, creators, and artists to taint our enjoyment of the art, no work would be pure.

However reprehensible his personal life has been, and however enticing it is to dismantle his entire career and drag each piece through the sludge of his presumed actions, for the sake of our history, we must rise above the temptation and extricate the onscreen character of Cliff Huxtable from the real-life character of Bill Cosby.

And in truth, had we done so when we were first introduced to both men, we might not be wrestling with the legacy of The Cosby Show today. We might still be grappling with his image as a sexual predator, but we would able to answer our essential question emphatically: No. Bill Cosby’s behavior should not taint the legacy of The Cosby Show.