In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to automatically sentence juveniles to a term of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Now, the high court will decide whether that decision should be applied retroactively to those youths who were sentenced to life before the 2012 ruling. The implications are serious for Black children, as juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) is almost exclusively a punishment reserved for children of color.

The court in Miller v. Alabama ruled that “mandatory life without parole for those under the age of 18 at the time of their crimes violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on ‘cruel and unusual punishments’ and that a ‘judge or jury must have the opportunity to consider mitigating circumstances before imposing the harshest possible penalty for juveniles.'”

The case came after the high court’s 2010 decision in Graham v. Florida, which struck down JLWOP in non-homicide cases, due to the fact that juveniles are less culpable for their crimes, and have a greater capacity for rehabilitation, reform, growth and change. In 2005, the court had banned the imposition of the death penalty for children convicted of capital murder.

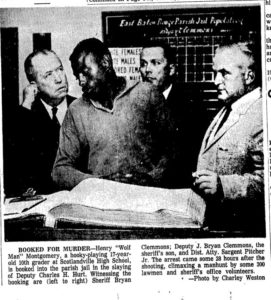

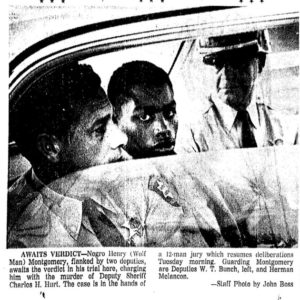

A file photo from a Baton Rouge, Louisiana, paper following the trial of 17-year-old Henry Montgomery, convicted for the 1963 murder of a sheriff’s deputy.

On October 13, the Supreme Court heard the case of case of Henry Montgomery, 68, who has been imprisoned with no chance of parole since 1963. Montgomery, who is Black, was convicted at age 17 for the murder of a sheriff’s deputy in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He wants the court to apply his conviction retroactively, with implications for thousands more like him.

JLWOP is a nearly exclusively American punishment that flies in the face of international human rights standards. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that “Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below eighteen years of age.”

According to the Juvenile Law Center, which filed amicus briefs in the Graham and Miller cases, there is no one serving this sentence anywhere in the world but in the U.S.

“A sentence of juvenile life without parole is cruel, unfair, and unnecessary. It sends an unequivocal message to youth that they are beyond redemption,” says Human Rights Watch. “It erroneously presumes that allowing youth

offenders a parole hearing (which is not a guarantee of release) would fail to protect public safety and be unfair to victims. It also ignores the differences between adults and children—differences we accept as a matter of common sense, and which science fully recognizes.”

Mirroring the practice of the death penalty (in which 2 percent of counties are responsible for a majority of the death sentences imposed, according to a 2013 study by the Death Penalty Information Center), five of the nation’s 3,000 or so counties are responsible for one quarter of the 2,341 people sentenced under JLWOP. This is according to a study from Phillips Black law firm, to be published in the American University Law Review. The five counties include Philadelphia—the nation’s leader with as many as 291– Los Angeles, Orleans (New Orleans, Louisiana), Cook (Chicago) and St. Louis. Although Michigan did not disclose data, as reported by the Marshall Project, Wayne County (Detroit) would have ranked near Philadelphia, given that the state contains one of the largest juvenile lifer populations in the U.S.

Further, the study found that nine states account for 82 percent of all JLWOP sentences (California, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina and Pennsylvania). The jurisdictions without JLWOP include the District of Columbia, Indiana, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island and Utah.

The 2012 Miller ruling impacted mandatory sentencing laws in 28 states and the federal system. Fourteen state Supreme Courts (Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, South Carolina, Texas, and Wyoming) have ruled that Miller applies retroactively while seven other states (Alabama, Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, and Pennsylvania) have ruled that the decision is not retroactive, as the Sentencing Project notes. Further, California, Delaware, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, and Wyoming passed sentencing legislation applying to JLWOP retroactivity.

It is estimated by the National Center for Youth Law that 26 percent of juveniles sentenced to prison for life were convicted of a felony murder, which is participating in a robbery or burglary during which a co-participant committed murder, with or without the teen’s knowledge. Further, 59 percent of juveniles sentenced to LWOP are first-time offenders, while nearly half (including 80 percent of girls) have been physically abused, and 20 percent (77 percent of girls) were sexually abused, based on data from the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. Moreover, JLWOP is a punishment reserved mostly for Black children.

“Youth of color are gravely overrepresented in the [JLWOP] population, raising questions about the rationality of the punishment,” wrote the authors of the Phillips Black report.

In 2008, Human Rights Watch reported that 60 percent of prisoners serving JLWOP are Black, and all but 2.6 percent of JLWOP inmates are male. According to the National Center for Youth Law, Black youth are sentenced to JLWOP at a rate 10 times greater than white youth. In California, 158 of the 180 juvenile lifers are youth of color, and in that state Black youth are 22.5 times more likely to receive life without parole than whites. Typically, such juveniles receive ineffective legal representation every step of the way, from pre-trial and plea proceedings to trial and sentencing.

According to Real Clear Policy, while Black youths are 17 percent of youths nationwide, they represent 30 percent of those arrested, and 62 percent of those tried as adults.