By Donnell Suggs

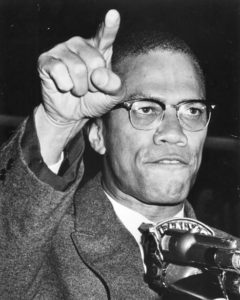

More and more examples of the precognitive powers of the words of the late Malcolm X display themselves today throughout the country. A prime episode of his clairvoyance came during a debate on Oct. 11, 1963, at the University of California, Berkeley.

[playwirevid id=’3724478′]

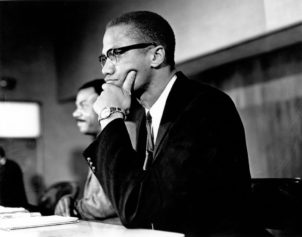

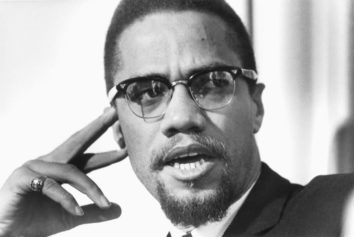

The televised event hosted by the university featured what would later become two of the most-heralded Black academic voices of the turbulent 1960s: Malcolm X, the minister of the Black Muslim mosque Temple No. 7 in Harlem, New York, and Herman Blake, a Korean War vet with a bachelor’s degree in sociology from New York University and a M.A. and Ph.D. in the same subject from Cal Berkeley.

Blake was working as a teaching assistant in the university sociology department at the time of this locally televised discussion and was presumably brought on to give his educated opinion while also making Malcolm X comfortable on what was clearly foreign territory. As the telecast would play out, it looked more like Blake was brought forth as an intellectual sacrificial lamb for slaughter.

At this point in time, Malcolm X had spoken the virtues of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad — the acknowledged leader of the Black Muslim movement in the United States and the Nation of Islam — all over the country and would later be invited to universities (most famously to Oxford University in London on Dec. 3, 1964) to give his take on what Black people in America was going through and how he and she were going to be an independent people. This way of thinking then and now does not invoke much positive media coverage. The message Minister Malcolm was sending to the hundreds and later thousands of people in Harlem that attended meetings at Temple No. 7 and before he was given the honorable position of minister on the street corners throughout the then-predominantly historic Black neighborhood. Today, Harlem can be found to host a number of tourists, whites and interracial couples who at one time would not have been caught dead between 110th and 155th Streets.

The debate started lightheartedly with a softball question from Blake about the validity of rumors that the Black Muslim movement was “an organization dedicated to the use of violent means to attain its goals.” This loaded questions leads Malcolm X on a soliloquy about how the Muslim followers of Elijah Muhammad are “taught to display courtesy and be polite” but were within their religious rights to defend themselves if violence was directed toward them. In comparison with many of the recent events that have garnered massive amounts of media attention stemming from violence (the police shooting unarmed Black males and/or females to death) Malcolm X was foreshadowing how the impact of this type of behavior by the authorities on the Black public should have been immediately approached by the Black public. Before we ever had a Ferguson, Missouri, we should have had the “religious right” to defend ourselves in the face of police or any other type of brutality.

Later in the broadcast, the host, a white male whose identity I have yet to discover, uses the recent bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church (which occurred only a few weeks before this debate on Sept. 15, 1963) in Birmingham, Alabama, as an example of a tragedy against Blacks — credit to him as he did refer to us as “Black Americans”– where the Nation of Islam did not retaliate in response to the terrorist act. Again Malcolm X’s response and the act of which he is responding to mirrors what is going on today with the shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17.

“Instead of arresting the discriminators the law arrests the demonstrators,” said Malcolm X. More than 50 years later, the sentiment in that statement rings as true today as it did in 1963. He followed that with the most important statement of the debate and a proclamation that seems more prophetic than anything else: “There will come a time when Black people wake up and become intellectually independent enough to think for themselves as other humans think for themselves then the Black man will think like a Black man and he will feel for other Black people and this new thinking and feeling will cause Black people to stick together and then at that point you will have a situation when you attack one Black man you are attacking all Black men. This type of thinking will bring an end to the brutality inflicted upon Black people by the white man.”

That way of thinking seemed to be in full effect in recent history with the #BlackLivesMatter campaigns and the protests — sometimes both violent and nonviolent — over the past year and a half.

“No federal court, state court or city court will bring an end to [it],” said Malcolm X. “This is something the Black man has to put an end to himself.” Apparently, Black lives mattered then, too, and just like today the legal system will not stop the nine lives from being lost in a church in Charleston like it did not stop four little girls from dying in a church in Birmingham.

Blake mentioned how he read in James Baldwin’s classic “The Fire Next Time” (1963) that Baldwin had once heard so-called Black nationalists speak from soap boxes from Harlem street corners and how he barely saw anyone stop long enough to hear these people speak, but when the Black Muslims started speaking to the public about educating themselves and independence, people stopped in large groups to listen. The message was essentially the same, the messengers were not, however. Malcolm X allowed that statement in the form of a question to linger for a (very) brief moment before comparing it to putting a “seed in the soil it remains beneath the soil until the season changes.” He was comparing the changes of the 1960s to the changes of today: social (social media movements going viral), economic (more Black-owned businesses than at any point in the history of this nation) and political (President Barack Obama) advances that had been planted long before Ferguson, Baltimore, Cleveland, Staten Island, Charleston and Trayvon Martin’s murder.

The debate closed with this question asked to Malcolm X: What would be the ideal solution to the racial problem in the United States today? There really is no answer to that question today like there was no real solution in 1963 when the question was asked. Separation of the races as Malcolm X suggested did not happen then and surely would not have a chance today. The question unfortunately still stands without a true answer.

Malcolm X’s visit to Berkeley would come less than two years before his assassination in 1965, but his words on that studio set through a black-and-white lens was anything but black and white. It was all black, and it was powerful and for 40 minutes and eight seconds it will go down as nothing less than prophecy.