Last week, the Hollywood Reporter revealed that Disney has an animated film in the works called The Princess of North Sudan.

With Black List writer, Stephany Folsom, penning the script, the production will chronicle the real life story of Virginia farmer Jeremiah Heaton, whose daughter Emily dreamed of becoming a real life princess. Intent on making her wish come true, Heaton set out on a journey for open territory, eventually stumbling upon a stretch of unclaimed land between Egypt and Sudan referred to as Bir Tawil. On his daughter’s 7th birthday, Heaton flew across the globe to plant a flag in the sands of Africa, officially creating the nation of North Sudan. With that, Heaton became the country’s first king with Emily reigning as the land’s noble princess.

Cute story right? An animated movie about a father’s voyage to the ends of the earth to fulfill his daughter’s wish of becoming a royal princess.

Not quite for some audiences, who view Disney’s newest endeavor as a fantastical glorification of a problematic issue long imposed by the western world. The fact that Heaton felt entitled to seize “unclaimed” African land because – according to The Guardian, he just “couldn’t let Emily down” – seems all too familiar considering the centuries old tradition of European colonization on the continent of Africa.

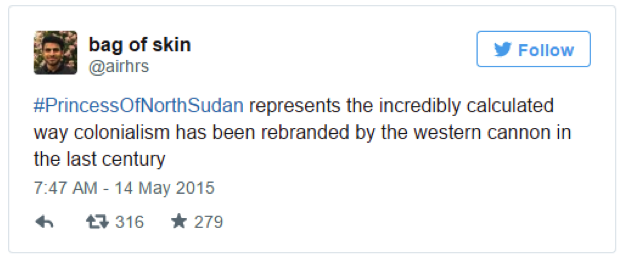

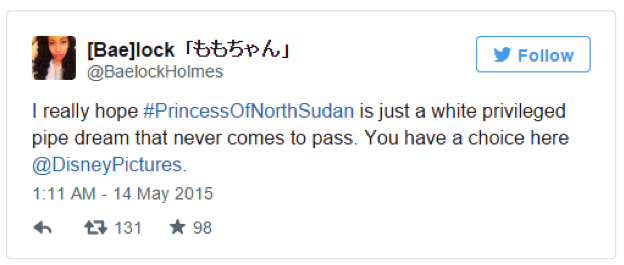

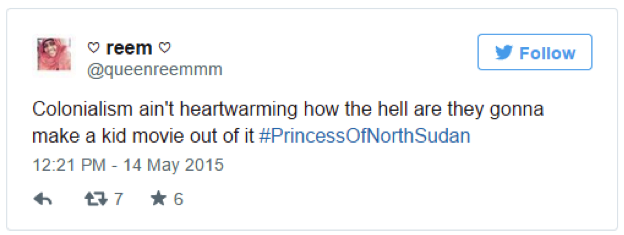

Hence the following reactions from the realms of Twitter:

Needless to say, people with at least a little knowledge of history aren’t feeling the concept of bringing a white Nubian princess to the big screen. But while Disney’s latest production brings about understandable feelings of anger and disgust, this of course isn’t the company’s first misguided cinematic representation of race, culture and history. In truth, the studio’s projection of questionable imagery dates back decades–from the stereotypical depiction of Native Americans in Pocahontas, to the unambiguously racist undertones in The Princess and the Frog, the corporation’s first film featuring Black royalty in its more than 90 year existence.

Now we have The Princess of Sudan, where Disney’s sole African princess is the offspring of a man who one day decided to channel his inner Columbus by stealing foreign land for himself and his family. All because he could.

Last week, in the wake of social media backlash over the movie’s premise, screenwriter Stephany Folsom responded to angry critics on Twitter, assuring that: “There is no planting a flag in Sudan or making a white girl the princess of an African country. That’s gross.”

She continued with a direct response to the article written by the Hollywood Reporter, “Rest assured that is NOT the story we are telling,” and later asserting that “…colonialism is bullshit.”

Well, Stephany Folsom, most audiences will agree that this sort of representation is indeed pretty “gross.” Beyond the obvious reasons, here are some additional points to demonstrate why this situation remains so problematic.

First, Bir Tawil’s status as one of the only global areas unclaimed by any continent stems from a legacy of British colonial rule dating back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1899 and 1902, the British drew two lines separating a corner of land along the Egypt and Sudan border, resulting in an ongoing dispute between the two countries over who owned the larger terrain. Today, both nation’s still claim the more sizeable region known as the Hala’ib triangle, with each denying ownership to the smaller, undesirable stretch of Bir Tawil (because naturally, neither Egypt or Sudan will concede the greater territory to the other country).

Thus lies the long lasting impact of colonial occupation: division, confusion and dissension stemming from the remnants of whites settling on land that didn’t belong to them in the first place. In turn, Heaton went on to exploit a location still reeling from lingering issues first imposed by colonizers more than 100 years ago.

Second, according to demographic statistics from Sudan and Egypt, approximately 70 percent of local natives identify as Sudanese Arab and 99 percent as ethnic Egyptians, respectively. So despite Heaton’s proud conquest of a barren land mass now referred to as “the Kingdom of North Sudan,” the majority of those living in that region look nothing like little Emily. So the question remains: Just what kind of message does this film send to young audiences with physical features resembling those actually living in this part of the world? Like Emily, aren’t little girls of African descent worthy of imagining themselves as royal princesses?

Finally, in this Disney-esque interpretation of a young, white American heroine ruling over the motherland, the film will inevitably present its fair share of antagonists. Will they look like the reigning princess? Or in typical Hollywood fashion, will the antiheroes be constructed to reflect the region’s native populations with dark skin, African features and stereotypical accents? Based on Disney’s dreadful history, we can definitely bet on the latter.

The bottom line is this: while The Princess of North Sudan presents itself as a magical fairytale about a father’s boundless love for his daughter, the movie’s actual premise is based upon the exaltation of white supremacy, long-lasting ideals of Western entitlement and the enduring tradition of white colonial occupation.

In the end, Heaton’s all-American quest to exploit a region still disoriented from European colonial influence is wrong, no matter which way you spin it. Likewise, Disney’s choice to reward these actions with a movie starring a white child as its only African princess sends yet another damaging message that Black girls aren’t worthy of being portrayed as onscreen heroines.

Bearing these facts in mind, The Princess of North Sudan is probably the worst way possible to introduce African royalty to young impressionable audiences–even within the questionable world of Disney productions.

Shelby Jefferson is a blossoming journalist, and currently works as a staff reporter for a Michigan based community newspaper. As a radical intellectual, writer, poet and pop culture junkie, she frequently uses her articles to analyze and present a broad spectrum of themes including race and representation in television/music/film/media, contemporary arts and culture, race and gender identity in sports and social justice issues in the United States.