More than 100 years ago, W.E.B. Du Bois conveyed the tightrope that is African-American consciousness – the “peculiar sensation” of seeing oneself through the eyes of others, “of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” He memorably wrote:

“One ever feels his two-ness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

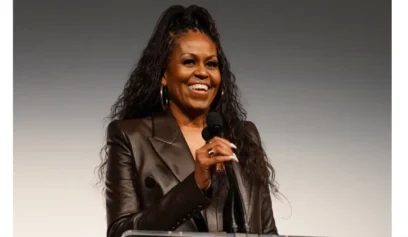

A century later, African-Americans who navigate Black and white spaces know well the delicate dance of being understood in two unsettled worlds. When first lady Michelle Obama recently addressed Tuskegee University graduates, her remarks were filtered through two distinct prisms and were viewed as volatile – at least in a segment — of one, and as welcome in the other.

Relating her own experience in the White House, she warned the new graduates of a future in which some “based on their limited notion of the world” will continue to make negative assumptions about them. She said she and the president know well what lies ahead. “We’ve both felt the sting of those daily slights throughout our entire lives — the folks who crossed the street in fear of their safety; the clerks who kept a close eye on us in all those department stores; the people at formal events who assumed we were the “help” — and those who have questioned our intelligence, our honesty, even our love of this country.”

Some on the conservative right pounced, viewing her comments as the bitter invective of a woman who did not appreciate the opportunities she had been given – as if her success somehow shielded her from the sting of bias, or precluded her from relating her experiences to those who may be inspired by her triumph over obstacles.

The minefield that is Black expression is most acutely apparent for those in the public eye whose every word is weighed on conflicting scales, but it is there for any of us who move between Black and white worlds. As someone who has spent her entire professional career expressing the reality of Black life to largely white audiences, I know the challenges well.

I spent a decade working as a daily newspaper reporter at four mainstream news organizations before joining the faculty at New York University, where I have been for more than two decades. And while some would view the experience as stifling, I have seen it as an opportunity to bring a well-honed double consciousness – the gift of our unique American experience — to a wider audience. There are times when using the shorthand that goes with communicating to a like-minded audience is a relief. But that comfort can at times restrict the flowering of a more nuanced and multifaceted language. It is precisely that refined bilingual and bicultural double consciousness that can render us uniquely poised to bring greater clarity and insight to complex issues.

In my books, I try – (and no doubt at times inevitably fail) — to avoid shortcuts of speech that will enable those of goodwill with whom I disagree to more readily shut out light. As such, I don’t automatically reduce those who have a different worldview due to their wholly different experiences as “racists.” Many whites live in worlds in which police officers are revered, and in which courts don’t routinely send nonviolent white offenders who made youthful errors to prison. So their positive view of these institutions – along with the persistent negative stereotyping of Black life in popular culture — colors their perceptions of those who are harshly targeted by the criminal justice system. Given the assumption by many whites that these institutions are inherently fair, they find it difficult to imagine an antithetical Black reality. Only in recent months, with a pattern of police violence against unarmed Black males caught on camera, are some whites beginning to question their flawed preconceptions.

First lady Michelle Obama waves towards the crowd after walking out on stage just before she delivers the commencement address at Tuskegee University, Saturday, May 9, 2015, in Tuskegee, Ala. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

These perception-altering moments highlight the importance of some of us being in spaces where we might bridge our disparate worldviews. There are those who will never accept the bite of unvarnished truth – and who will only see the first lady’s perspectives as evidence of bitterness, lack of patriotism and ingratitude. However, the stakes are too high to avoid the inherent risks of communicating across racial fault lines.

In my first book “Within the Veil: Black Journalists, White Media,” I wrote about the challenges Black reporters face in mainstream news organizations where they often find themselves swimming against the tide in their newsrooms; and of how their ideas are often viewed with suspicion or alarm. I chronicled a series of newsroom episodes that pitted Black journalists against their white colleagues. I wrote about the backlash against attempts by Time magazine journalist Sylvester Monroe to provide a nuanced portrait of Louis Farrakhan. Some conflated Monroe’s attempt to view Farrakhan with the objectivity accorded other leaders as proof of his own racial biases. In reality, he was merely applying his journalistic training to a prominent newsmaker. Bryant Gumbel, at the time one of the nation’s most visible Black journalists as a NBC-TV Today Show host, spent years trying to take the show to Africa, the only continent other than Antarctica, it had not gone to. He finally convinced the network of the newsworthiness of the continent – but only after presenting a doctoral dissertation-like document. While shedding light on patterns of institutional shortcomings won’t transform the news industry, it might lead some news executives and reporters to question their innate biases.

More recently I wrote about the return of many high-profile Black journalists to Black-interest publications where, with an unfiltered voice, they can more directly tackle the kinds of issues that fuel their passion as journalists. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of Blacks working in mainstream newsrooms plunged 34 percent. The numbers have since stabilized and not all left for the same reason, but I know from experience the toll negotiating double consciousness can take.

But in the end, many of us will find ourselves navigating worlds with colliding racial and cultural perspectives. And we will need our public officials, journalists, academics and others operating in both predominantly Black and overwhelmingly white spaces. Our keen insight as African Americans is essential to the dialogue both within our own community and to a wider public. And our hard-earned ambidexterity is not an impediment; it’s a gift.