For the first time since the U.S. started its climb to economic recovery, the Black unemployment rate has fallen to the single digits.

On the surface, it seems like a reason to celebrate and hope that things are finally taking a turn for the Black community.

Economists, however, are warning that this may not actually be the beginning of significant change or a turning point for Black people.

The unemployment rate in the Black community recently dropped from 10.4 percent to 9.6 percent, and the racial gap in labor force participation has narrowed more than it has ever done in the past.

According to experts, however, this is the usual cycle that takes place during an economic recovery, but it is too often followed by yet another dramatic blow to the Black community.

“When the economy reaches the end-stage of a recovery — as the country reaches full employment — African Americans tend [to] see a sudden improvement more dramatic than the rest of the country,” according to The Washington Post. “And that’s what’s happening now, according to economists, who say that tight employment is the best way to bring down the black joblessness rate.”

In other words, the drop in the unemployment rate is so dramatic because the Black community had been pushed so far behind during times of economic hardship.

Their white counterparts, on the other hand, are usually not impacted as much by blows to the nation’s economy, leaving little room necessary for them to “bounce back” after something like the Great Recession.

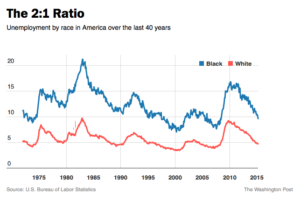

At any point in time, however, the Black unemployment rate has remained significantly higher than that of their white counterparts’ for decades.

For more than 40 years, the unemployment rates for both communities have bounced up and down and it’s likely that we are seeing the slight economic ascension that could come before yet another great fall for the Black community.

But is there a way to break free of such a pattern?

Economists believe it won’t happen until the nation starts dealing with issues that are rooted even deeper than just job creation.

It’s only fair to note, however, that even when two candidates have the same educational level, a white candidate has been proven to be far more likely to get the job than the Black candidate.

For that reason, mass incarceration proves to be one of the greatest factors involved.

There are a plethora of hiring obstacles facing those who have even the slightest blip on their criminal record and multiple studies have shown that these criminal pasts have a greater impact on Black applicants than white ones.

Since the criminal justice system is yet another racially biased obstacle the Black community has to hurdle over, it’s easy to see how many more Black would-be employees are left struggling to find work.

So while the drop in Black unemployment is an exciting fact that some have been very optimistic about, it doesn’t mark a real victory just yet.

“It’s not just about getting to full employment that helps minority workers,” Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told The Washington Post. “It’s getting there and staying there.”

Only time will tell if that’s truly the case this time around or if the decrease was nothing more than a glimmer of false hope.