There have been questions surrounding the mystery of the theory of Afrofuturism. Actress Jada Pinkett Smith referred to her 14-year-old daughter, Willow Smith, as her “little Afrofuturist” on BET’s Black Girls Rock, also a nonprofit organization, which celebrates the accomplishments of younger and older Black women. Live tweeters on Twitter excitedly expressed how pleased they were that Pinkett Smith mentioned Afrofuturism. For others, there was some confusion. The confusion is understandable considering that there is not one singular definition for Afrofuturism. It is also understandable considering that in 1992 white social critic Mark Dery coined the term. Afrofuturism conceptually is ancient, but when white people not truly understanding the Black experience partake in the naming process, it can become problematic.

Furthermore, the uniqueness of Afrofuturism is that the definition is dependent upon the interest of the Afrofuturist. What does that mean? The Black comic book and cosplay connoisseur could have a drastically different definition from an Africana Studies scholar. To complicate the mystery of Afrofuturism depending on the angle of the Africana Studies scholar, their definition could be different from other Africana Studies scholars. Although, there may not be a right or wrong definition when it comes to the theory of Afrofuturism, there must be certain guidelines that this methodology must follow. The criteria involve the future of African people of the diaspora.

What is Afrofuturism?

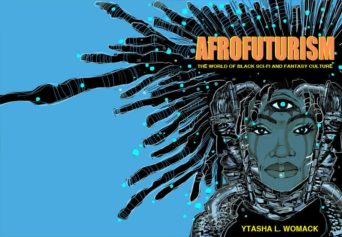

In author, futurist and filmmaker Ytasha Womack’s text “Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture,” she defines Afrofuturism as “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future and liberation (p. 9).” Alondra Nelson in “Future Texts” defines Afrofuturism as “African-American voices” with “other stories to tell about culture and technology and things to come.”

While these things may be true, I have chosen to expand on these definitions by creating my own. In acknowledging like other Afrofuturists that the oppression of African people plays a factor in how Afrofuturism will interact with the rest of the world, I realize that sometimes the fanciful elements often override the actual reality of Africans. At the same time, some Afrofuturists underestimate just how practical Afrofuturism can be for all African people of the diaspora. It is very difficult to discuss the future of African people while leaving out the past and our present conditions; present conditions that are the result of an egregious system such as white supremacy.

I define Afrofuturism as a concept, practice and movement that requires Africana people to ubiquitously conceptualize and deduce time from the past, present and future from an African cultural center. This cultural center operates as the technological component of African futures from which African people can architect their agency in memory and in practice.

This concept uses the Akan principle of Sankofa, which means to “go back and fetch it.”

Why Afrofuturism?

Technology has been used as an oppressive tool for anti-Black/white supremacist gain because human life has become the technological tool. Africana people are an “other” within an anti-Black and patriarchal white supremacist society, creating dehumanizing and post-human classifications for Africans of the diaspora. Afrofuturism from the perspective of Africana Studies seeks to (or should) dismantle ideas of post-humanism by reinforcing Africana humanism. While white supremacy’s tools have been used to dismantle and distort the Africana personhood, Afrofuturists engage African culture as the technology most capable of enabling African futures.

For Afrofuturist and Temple University African American Studies doctoral student Jennifer Williams, #AfrofuturismMatters. On Twitter, Williams (@beingpurposeful ) states, “Afrofuturism is so dynamic and tautological, I think that there are multiple intentions and many ways to engage Afrofuturism… and we might have to plan and develop many of them in Afrofuturist ways.” Some choose to engage Afrofuturism artistically, and Williams as an Africana Studies scholar observes this medium as a necessity and asset to Afrofuturism.

Humanism, the Post-Human and the Other

Afrofuturism participates in a coded language. Some superhuman and post-human coded terms are used to describe the lens at which Africans of the diaspora are seen. This language reveals that Africans are the “other.”

Marlo David, in an essay titled “Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular Music,” states that “humanism, no matter how politically and socially utilitarian it has been to the project of Black liberation, has remained a space of “always, but not quite” in black cultural production; it has been a rhetorical and ideological tool in a trick bag of survival.”

Some Afrofuturists take the position of embracing post-humanism as a way to compensate for white supremacy’s dehumanizing view of Africans. This view is as equally problematic because dehumanization and post-humanism both reject the idea of Africans being human.

Some Afrofuturists embrace post-humanism from a spiritual viewpoint. “Let the Circle Be Unbroken: The Implications of African Spirituality in the Diaspora” by Africana Studies scholar Marimba Ani discusses this idea of being human from a spiritual perspective. Ani states, “Spirituality in the African context does not mean distant, nor does it mean “non-human” and it certainly does not mean “saintly” or “pristine.”

David posits that the idea of humanism has “come under suspicion for its hegemonic assertion of Enlightenment ideals of the liberal white male.” This is why even though Africans are human; we must define what an Africana humanity is.

The “android” is a frequented term used in Afrofuturism. The android is not to be confused with a cyborg; a human with machine body parts. The android is made entirely of machine parts, possesses a higher intelligence and human characteristics, which include a human-like resemblance. Despite its physical appearance, the android is not human. The assumption is that androids are not capable of loving or having the ability to feel other emotions. Androids cannot dream.

The case of the android seems all too familiar to the African. May it be the three-fifth’s compromise or a young Black man of 17 named Mike Brown lying down slain by a white police officer for 4 1/2 hours like roadkill, Africans, Black people, know the story of white supremacy’s constant effort to dehumanize us like a recurring nightmare. For over 300 years, Africans have fought to prove that we are not animals, but that we are the start of what is human. All humans, like androids, are programmed starting from birth to perform. With this programming, rights dependent upon race or class are assigned, gender roles are assigned, as well as being assigned other roles. The programming of Africans by a white supremacist system (the programmers) that seeks to oppress, has the ability to hardwire Africans to perceive ourselves as worthless and easily expendable. These programmers are insidious because as film critic Richard Dyer states, which can be found in “The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: Racialized Social Democracy and the “White” Problem in American Studies” by George Lipsitz, “White power secures its dominance by seeming to be nothing in particular.” This programming is like a disease, but from an Afrofuturist’s perspective there is a cure.

The cure is to reprogram African minds. There must be a malfunction and disruption to this system — to this African mind and body. The technological tool that must be used to cure this disease or rewire this programmed mind is the African cultural center. It creates a storage of sankofic memory. This is coded language for Black consciousness and African/Black agency. This reprogramming is something that white supremacists hate, which will cause them to stop at nothing to erase and discard this type of enlightenment. Moreover, the Afrofuturist while still being cautious understands that this reprogramming is necessary to the project of progressing African futures.

On Twitter, Williams states that Afrofuturists must “perform a small act of Africana liberation today, so you can build up to larger acts in the future.” Afrofuturists do not have all of the answers in terms of performing these “small acts,” but many to find these answers are doing the work.