The most provocative artists use whatever they can find within their reach to comment on the world around them. Their commentary can be obvious and open, or sometimes it can be dark and private and only they really know what the images and forms are saying.

The work of Trenton Doyle Hancock, now on display in an exhibit at the Studio Museum in Harlem, sometimes seems to be all of those things at once. His drawings at first glance appear to be whimsical and playful, but when you look closer the darkness starts to emerge. There are disturbing, dramatic things going on here.

What’s going in is Hancock is using his art to subversively comment on the plight of Black males in America. It’s there in his Studio Museum exhibit,”Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing.” But it’s not always thrown in your face.

“I think for Trenton, being black and being male, to be an artist is sort of an anomaly for him,” Valerie Cassel Oliver, senior curator at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, told the Huffington Post. “People like him often expect to be incarcerated. He realized that being a black man and being an artist is a rarity, it’s a gift, because he was supposed to be something completely different. Understanding those injustices exist make him want to talk about it … to bring it more or less to questions about morality. Often times morality is not simply black or white. I think his visual mythology gets to that.”

His exhibit is overseen by Associate Curator Lauren Haynes.

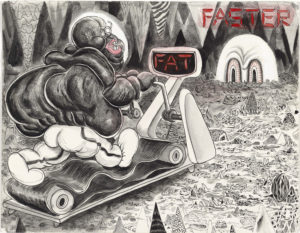

Born in Oklahoma City in 1974 and raised in Paris, Texas, Hancock shows the traces of his Southern upbringing in pieces that mix together many of his influences, such as graphic novels, cartoons, music and film.

“He was definitely influenced by comic books and later underground comic books,” said Oliver. “Things like [Robert] Crumb and also things that are more highbrow, like folk art. There are a lot of influences that go into Trenton’s visual language. It goes from a punk aesthetic to a Renaissance aesthetic. He has a profound love of toys as well — playing cards, The Garbage Pail Kids, the old Godzilla figures. He truly does drink in everything.”

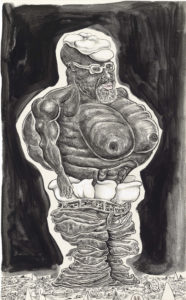

Writing in the Huffington Post, Priscilla Frank says of his pieces, “If a (wildly talented) stoned teenage boy had his way with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, it may resemble Hancock’s chockablock creations.”

“Looking at Hancock’s artworks, his hoarder aesthetic is more than obvious. Traces of Peter Saul, Kenny Scharf and Gary Panter fight for room on the clustered surfaces, teeming with squiggly torsos, bulging, bloodshot eyeballs, spindly legs and bubble butts,” she writes.

“There are these questions about a moral compass, done in a way that’s very accessible,” Oliver explained. “It’s not dogmatic; it doesn’t point to one thing or another. But rather, it allows people to examine it from afar and then coming full circle and letting people adjust their own internal compass.”

But race is never far from the surface with Hancock. For instance, one of his favorite motifs is cartoonish Klansmen. He was particularly shaken when he learned of a lynching that occurred in 1893 in his hometown of Paris.

When Hancock was awarded the NAACP award in Paris, Texas, his grandmother, who introduced the prize, gave an introduction which included information about the dark histories of landmarks sprinkled throughout the town, Frank writes.

“Hancock could not understand the history and the gravity of these landmarks,” Oliver explained. “Hearing his grandmother, his mother, his aunt, talk about having different experiences with the different generations there, he realized there was this history of Paris that involved lynching. The Paris Fairgrounds he would go play on as a kid — his grandmother couldn’t even get near there. There was this moment about understanding the various intersections of history, and Trenton was bringing all of these divergent, seemingly unrelated histories together in one place.”