The lack of diversity in the admissions classes to the city’s elite public high schools has been a matter of intense scrutiny and criticism for decades, as the strict adherence to a 2 1/2 hour standardized test for admissions has locked generations of Black and Latino students out of these schools. Many different proposals for increasing Black and Latino representation in Stuyvesant High School, Bronx High School of Science and Brooklyn Tech have been suggested over the years, while the student bodies go largely unchanged from year to year.

The competition to get in these high-performing schools is especially acute in a city where private high schools can easily surpass $40,000 a year—nearly the tuition for many of America’s elite colleges. So for an average New York family of means, admission to a school like Stuyvesant could mean a savings of nearly $200,000.

That explains why there has been such a fervent opposition to any proposals to change the schools’ admissions criteria to make it more closely reflect the city population. There is too much at stake for too many.

While Black and Latinos make up around 70 percent of all the students in the city’s public school system, they are just a minuscule share of the population at those three schools. Stuyvesant, the crown jewel of the city’s elite, had 113 Black and Latino students in the total student body of 3,296 this year—less than 4 percent of the total student body.

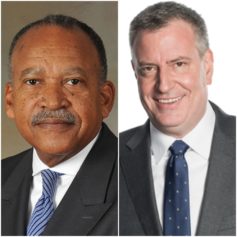

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund filed a lawsuit with the Justice Department in 2012, questioning the test’s fairness. Others, including mayor Bill de Blasio, argued for a more “holistic” set of admission parameters that would be far-ranging and not place the entire emphasis on one test.

But the NYU study found that using using an alternative admissions criteria — taking some combination of grades, state test results and attendance into account — would pull in many more girls, more whites, more Latinos and fewer Asians, while failing to boost the numbers of Black students. In some cases, the report found, it actually might lower the number.

“Maybe it was naive, but I thought if you switched to more holistic measures, it would diversify the admissions pool considerably,” Sean Corcoran, one of the researchers, told Sara Danville of GothamSchools.

Under another proposal that would guarantee entry to the top students from every high school, it would make the elite high schools more diverse, but that would come “at the cost of reducing the average achievement of incoming students.”

As pointed out by The Atlantic’s Alia Wong, the problem starts long before the students actually get to high school. It starts when students are “tracked” in earlier grades.

“[A]mong the students who came from one of the top 30 ‘feeder’ middle schools, 58 percent were in gifted and talented programs that required a test for admission, and 29 percent were in other types of screened schools that admit kids based on criteria such as exam scores,” Wong wrote. “This phenomenon is also known ‘tracking,’ which even the DOE has described as a ‘modern-day form of segregation,’ and indicates that a much deeper problem lies in the tendency to test and segregate children from the get go. The analysis raises questions about the extent to which inadvertent engineering—starting with the so-called ‘rug-rat race’ —is exacerbating the achievement gap.”

The paltry numbers of Black and Latino students accepted at these specialized math- and science-focused schools significantly impact the numbers of Black and Latino students who ultimately pursue degrees or careers in STEM fields down the line.

And as the debate rages on, the numbers continue to induce pain: among the acceptance letters that went out to admitted students to Stuyvesant last month, there were just 10 Black students out of 953 spots.