Give college basketball a hand for what has happened in the last week.

Yes, the NCAA Tournament delivered as March Madness somehow, amazingly, always does, and tonight’s National Championship game between Wisconsin and Duke promises to be the ideal climax to another captivating tournament.

But even more interesting and important than Kentucky losing to the Badgers Saturday were two hires of coaches over three days that is a nice start toward addressing the embarrassing coaching racial disparity in college basketball.

We will not dare assume any responsibility for the movement since a column a week ago in Atlanta Blackstar called out college basketball for its lack of Black coaches in Division I. Wink, wink. But let’s just say . . it is quite a coincidence that two major programs have made two major hires of Black coaches.

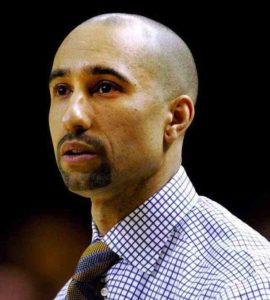

First, Texas, a state that is not exactly known as a beacon of racial fairness, hired Shaka Smart away from Virginia Commonwealth. A few days later, Avery Johnson, the former NBA coach, agreed to take over Alabama.

This is progress, especially when you consider:

* The Longhorns had never had a Black head coach in football in its history, and yet it hired Charlie Strong as its leader last year. Strong move, pardon the pun. To add Smart to the mix as the basketball coach gives Texas Black coaches of its two major sports—something that is virtually unheard of outside of HBCUs. Strong and smart.

“I take that really seriously,” Smart said. He won at least 26 games in each of his six seasons at VCU, a feat matched only by Duke. His teams reached the NCAA tournament five times. The Longhorns have the wealthiest athletic department in the country, and easy access to some of the nation’s biggest recruiting grounds in Dallas and Houston—a reason they can pay him $3 million a year.

* Alabama fired Anthony Grant, an African-American who was not horrible—117-85—in six seasons in Tuscaloosa, but not galvanizing, either. Ironically enough, his departure from VCU in 2009 opened the door for Smart to take over that program and enhanced what Grant started.

A Black coach failing usually means the “Black experiment” did not work and the next Black coach to get a chance at that school hadn’t even been born yet. But there is Alabama—Alabama—locking in Johnson in back-to-back

Black head-coaching hires that is hardly ever seen. Yes, the Crimson Tide first pursued Wichita State’s Gregg Marshall, who used the offer to get more money and stayed at Marshall. But Crimson Tide athletic director Bill Battle could have passed over Johnson and gone with a safer, whiter choice. To his credit, Battle sought the best bang for his program.

These hires are a commendable start to dealing with an ugly NCAA problem. African-Americans make up just 17 percent coaches while Black players make up 60 percent of the participants. The disparity is so glaring that two organizations have formed to attack the problem: Athletes for Athletic Equity (AAE) and the National Association for Coaching Equity and Development.

The AAE seems to be prepared to take the methodical, tactical approach to improving the numbers. The NACED, made up so far of about 40 coaches, are more rebels who plan bold initiatives.

“I’m glad (Atlanta Blackstar) pointed out the low numbers,” Tyrone Lockhart, CEO of AAE, said. “It’s out there for everyone to see. We’re going to create events and situations to show that Black coaches and coaches of all minority heritages deserve opportunities. That’s my charge.”

Smart and Johnson qualify as progress. They have jobs at major programs in major conferences. If they win, they surely will open the way for Blacks to get chances.

That’s how it works. One or two programs show gumption to hire a Black candidate and, if those coaches are successful, other Black candidates get more looks.

But it will be imperative for the two organizations to grow the pool of candidates by helping prepare assistant coaches to advance into head jobs. There are countless cases of white assistant coaches moving from the bench with a clipboard to the top position with a program in a matter of years. That hardly happens with Black coaches, and that has to change. Increasing the number of qualified candidates is the fastest way to improving the numbers.

Johnson and Smart are two coaches in prime positions now who can influence job opportunities for dozens of African-Americans pining for an opportunity. They are a nice start. More to come. . . hopefully.