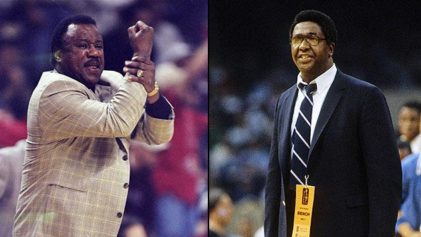

Tyrone Lockhart, who played for Georgetown in the 1980s, is CEO of the Advocates for Athletic Equity.

In a matter of months, Black college basketball coaches went from not having an organization to support their cause and chime the bell for a change in hiring practices to two bodies that will take different paths to achieve the same mission.

The National Association for Coaching Equity and Development was formed to address the lack of African-American coaches in Division I college basketball. It has 40 coaches on board, including Tubby Smith, John Thompson III, Shaka Smart, Paul Hewitt and others.

In Indianapolis, in the NCAA headquarters building, is the Advocates for Athletic Equity, an organization headed by former Georgetown player Tyrone Lockhart. Its mission is to increase the dismal number of minority coaches, focusing on all ethnic groups.

Both organizations say they are picking up where the now-defunct Black Coaches Association left off. Once a force in fighting causes for African-Americans in the profession, the BCA faded with a lack of funding and, not coincidentally, so did the number of Black coaches.

Blacks now make up less than 17 percent of head coaches in college basketball’s 330 or so Division I teams while African-American players represent 60 percent of the athletes. It’s the lowest percentage in 20 years.

Smith and others see their organization as totally independent and seemed to indirectly convey that the Advocates for Athletic Equity, because it is housed in the NCAA offices in Indianapolis and has received some start-up money from the governing body, will be less aggressive or compromised in its efforts.

Lockhart, in an exclusive interview with Atlanta Blackstar, refuted that notion while outlining his and the organization’s plans for change.

ABS: How do you look at the National Association for Coaching Equity and its mission?

Lockhart: The two organizations have talked. We’re supportive of each other. They may have to do things a little more drastic, whether that’s lawsuits, whether that’s protests … We understand that. We’re supportive. We both have the mission of increasing the number of (Black) head coaches. Tactics and strategy achieving those goals may be a little different. Hopefully, we will be able to partner on one of the key elements that we both agree on, which is professional development. … It’s like the Civil Rights movement in that the NAACP and the Urban League were separate entities working for the same cause.

ABS: How will you go about business with the Advocates for Athletic Equity?

Lockhart: Because BCA was dormant for a while, we’re housed at NCAA. Housed there, but separate computer system, separate phone lines. The NCAA believes that this organization is extremely important to be successful with what’s going on in college athletics right now. They are, in fact, providing some seed money in order to revive it and make some progress. But I report directly to the (AAE’s) board. Yes, there will be some things that we decide that will be opposed to what the NCAA stands for or believes in. But we will decide as an organization what will be effective for our mission (not the NCAA).

ABS: How alarming is the 17 percent Black coaches in the NCAA to you and the organization?

Lockhart: The numbers are low, and we know that they are low. My job to work with the membership and strategize on how to attack that. Our No. 1 priority is to promote our coaches for positions of leadership. The one thing, too, with the organization is that we’re focusing on coaches and coaches only. In the past, Floyd Keith had done an excellent job at bringing the organization to prominence and having some growth. But I think the organization took on too many things: athletic administrators, etc. My marching orders are to focus in on coaches and coaches only: African-American, Hispanic, Latino, Asian and so forth. That’s our charge.

ABS: Does a variation of the NFL’s Rooney Rule, which requires Black candidates get an interview before any teams hire, have a place in your approach to change in the NCAA?

Lockhart: We would favor any role or program that favors ethic minority coaches. The NCAA does not do the hiring; it’s the member institutes and the conferences. So, in working with our coaches, we have to ask: Do we partner with the NCAA or do we go directly to the conferences or the member institutions? We need to make sure we’re targeting the right group to make the most impact.

ABS: How do you tackle athletic directors, 80 percent whom are white who over the years hired people who look like them, who they know or are comfortable with?

Lockhart: The part in your piece about colleges hiring search firms and “Good ‘Ole Boy Network” is true, and one of the things we have to do is infiltrate that and establish networking opportunities, social interactions where we can get our top coaches a part of this deal and be able to highlight our coaches and the good things that they have been doing. For years, part of (athletic directors’) stories has been, “Well, we don’t know these coaches. We don’t know where they are. They’re kinda hiding out.” But we want to establish relationships and events where our coaches are featured and highlighted and can change mindsets … show they can handle crises, etc. There is no doubt that Black coaches are talented and can coach. No doubt. We have to show … they can handle the off-the-court stuff so a president or A.D. can be comfortable with those leaders on the court and off the court in the community. We have a great opportunity. We know the task is uphill. But we’re taking it on.