But with a closer look into the backgrounds of some of the alleged attackers and the historical impact that background checks have had on the Black community, a more vital concern seems to be getting overlooked. For years, background checks have disproportionately barred Black citizens from employment even when they showed no signs of posing a threat to a company or the consumers that company served.

The current discussion about background checks is much more focused on the fact that companies that conduct background checks through private consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) are still hiring violent employees.

The immediate proposal was to force all companies to shift to fingerprinting job applicants to ensure their entire criminal history is reported.

As it turns out, however, fingerprint scanning actually may not be any safer and it only adds to the problem of discriminating against Black job applicants.

“But the intense focus on fingerprinting is grounded in two faulty assumptions: First, that fingerprint-based background checks are orders of magnitude more accurate than privates ones (they’re not),” The Atlantic reports. “And second, that evidence of past criminal history is always a stronger indicator that a job applicant will engage in misconduct on the job (it’s not).”

It’s clear to see how relying on fingerprinting as a more secure method is a faulty proposal that wouldn’t ensure any added security for consumers, but based on the fact that the criminal justice system disproportionately targets Black citizens, fingerprinting could drastically exacerbate an already severe problem.

Minor blips on people’s criminal records are barring them from employment opportunities and disproportionately impacting the Black community.

“Racial disparities exist in every stage of our criminal-justice system, from arrest to trial to sentencing, and as a result, black people are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of white people, and Latinos at nearly twice the rate,” The Atlantic notes.

When all the pieces are placed together, it creates a clear image of how Black people are trapped in vicious cycles of poverty as the ironclad doors to opportunity are slammed in their faces.

After being targeted by a racially biased justice system, they are unable to obtain a normal quality of life even after being released—after serving the time and sentence that the criminal justice system has deemed a proper punishment for their crimes.

For too many Black people, their sentences are being extended to last a lifetime because background checks that frequently misinterpret how serious a crime was and when it occurred are telling potential employers that they are the menace to society that doesn’t even deserve a chance to work for a living.

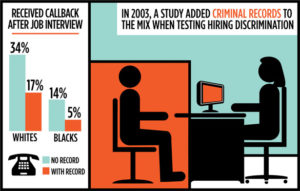

To make matters worse, Black people are not only judged unfairly in the eyes of the criminal justice system, but they are unfairly judged by employers as well.

It means Black people are already disadvantaged when it comes to seeking employment. Adding fingerprinting and continuing to use error-filled background checks will only continue to disproportionately impact the Black community, which could be deemed illegal under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The legislation not only makes it illegal to discriminate against applicants based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin but it also restrains the use of hiring policies that disproportionately impact a particular group.

In this case, a widespread ban on hiring people with any criminal record when it has been proven that Black people are targeted by the legal system and frequently racially profiled, could be grounds to call for more clear regulations on background checks as an entirety.

In addition, the simple truth is that background checks are not always a clear indicator of what type of an employee a person might be.

Ironically enough, one of the Uber assaults is the perfect example of this.

An Uber driver in San Francisco who was charged with attacking a passenger with a hammer had no criminal history that would show up on a background check.

Other people who could be stellar employees are prohibited from getting a position simply because they had a lapse in judgment years ago.

So rather than finding ways to ensure background checks are picking up every blip on someone’s criminal past, perhaps the real discussion should be figuring out how to properly utilize the information from background checks to more accurately decide whether or not someone’s criminal past is still something to consider when deciding the future of their career.