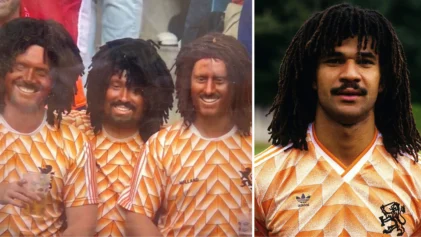

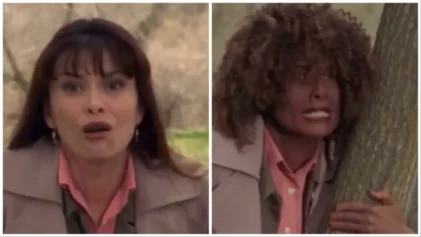

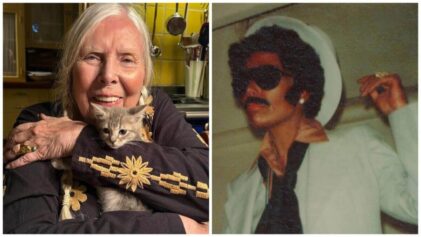

Reynders apparently thought it was appropriate to blacken his face at the event by Les Noirauds, an organization under royal patronage that was founded in 1876 and collects money for children’s charities. The attendees were to dress as 19th century African noblemen. Along with the black painted faces, they also sported white top hats, ruff, bright green pants and stockings—hardly African noblemen garb.

And it was hardly funny to African people and organizations. By the way, Belgium does not have a national anti-racism plan, although it committed to creating one 14 years ago at a United Nations conference in South Africa.

This kind of affront underscores the continual disrespect of Africa and Black people around the globe. When a foreign minister of a country participates in the lunacy instead of calling for an end to it, it illustrates the embedded and pervasive racism that is considered acceptable.

Woter Va Bellingen, the director of the Minority Forum, called Reynders’ participation “deplorable.”

Remarkably and contradictorily, Reynders stressed the importance of Central Africa in Belgium’s foreign policy on his website, but at the same time posted pictures of himself in Blackface, boasting about collecting funds for children’s charities. He either does not get it or does not care. Either way, particularly for someone in his position, it is reprehensible.

Reynders received little criticism from political parties in Belgium over his antics and the left-leaning Greens called it “innocuous folklore.” But some minority organizations and prominent Belgians of African descent said the foreign minister’s participation was unacceptable.

Most notably, Nigerian-born author Chika Unigwe said: “In other civilized countries his political career wouldn’t survive this, but in Belgium he just continues.”

The largest country in central Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo, was a Belgian colony until 1960. Millions of Congolese are estimated to have died and the country was decimated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when Belgian King Leopold II ran Congo as his personal play land.

This kind of display by the foreign minister juxtaposed with the history compounds the outrageousness of the event.