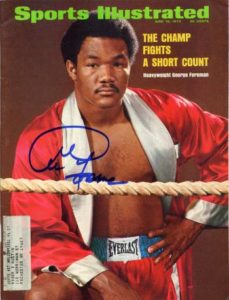

It’s pretty amazing that all this time later, George Foreman remains relevant. More than that, Foreman, once a boorish and mean oaf, has done so by becoming corporate America’s No. 1 pitchman.

It is a position he holds unrivaled, and one no one would have pegged him for after he became this behemoth knockout artist with no room for cheer.

But after losing to Jimmy Young in 1977, Foreman said he had a “religious experience.” In that moment in the locker room he decided to retire from boxing and eventually became a born-again Christian.

It also was the beginning of him morphing into a Black man who would become the face of white corporate America on a significantly larger scale than O.J. Simpson and even Michael Jordan.

Foreman told Sports Illustrated that he mimicked John Wayne when he walked; he adopted mannerisms like boxing champion Sonny Liston; and shaped his mustache after all-time great running back Jim Brown—three men with imposing reputations. He released those elements when he retired.

“It took so long for me to find me,” he said to the magazine. “Once I did, my mom even liked me. She didn’t like me much when I was trying to be those other guys.”

Ten years after retiring, Foreman, in need of money, returned to boxing with not much fanfare. Promoter Bob Arum recalled to SI: “I was not enthusiastic, realizing what a horrid person he had been.” But after spending an hour with Arum said, “This is the greatest con man in history because he was so different from what he had been before. But it wasn’t a con. He had really changed.”

That change made him an embraceable pitchman. It helped that he knocked out Michael Moore at age 45 to become the oldest heavyweight champion in history.

His always-grinning disposition bordered on buffoonery, but he laced his persona with enough wisdom, gospel and Black empowerment for it to be more congenial than a caricature.

Suddenly, with the historic victory and this warm and fuzzy person came offers to endorse products. Foreman told SI he had been hesitant about putting his name to products. But in 1991, none other than Bill Cosby called Foreman.

“I don’t want to be on TV saying this and that,” the champ told the comedian.

Cosby, Foreman said to the magazine, was not having it. “Come on, man. You’re no different from anyone else. You want to be on television, you want to be known,” Foreman remembers him saying. “If you don’t take ’em, I’ll take ’em.”

That was the moment Foreman became the all-time pitchman. Over the years he has done commercials for Nike, Doritos, McDonald’s and Meineke. The deal that made him rich and famous came in ’94, when he agreed to lend his name to and appear in commercials for a line of indoor grills. The George Foreman Grill became a blockbuster hit, earning him more than he ever took as a boxer.

He made so much money off the grills that in 1999, Salton Inc., the maker of the product, gave him $137.5 million in combined stock and cash to avoid having to continue paying him royalties, SI reported.

He became the spokesperson for InventHelp last year, a company that helps people get patents for prototypes of products. He’s also launching Foreman’s Butcher Shop, a mail-order meat company with an emphasis on quality, health-conscious products sourced from family farms in the Midwest.

Why does Foreman push products on all media platforms and speaking?

“Never say no,” he said is his approach.

He does, however, have other interests. His George Foreman Youth Center in Houston has existed for years as a place Black kids come to play sports and learn life lessons.

“The kids would come in and want to learn to box,” Foreman has said. “They wanted to tear up the world, beat up the world. And I’d try to show them they didn’t need anger. They didn’t need all that killing instinct they’d read about. You can be a human being and pursue boxing as a sport.

“When you speak to a lot of kids, as I’ve done over the years, you know what to say, keep them laughing, (giving them) good illustrations and (stressing to) learn to read.”

“If that fight hadn’t turned out like it did, my life would have been very different,” Foreman said. “I have no regrets. They’ll be talking about it for 100 years, and they’ll always have to mention my name.”

He now calls Ali one of his best friends.

“After 1981, we became the best of friends,” Foreman said. “By 1984, we loved each other. I’m not closer to anyone else in this life than I am to Muhammad Ali. Why? We were forged by that first fight in Zaire, and our lives are indelibly linked by memories and photographs as young and old men.”