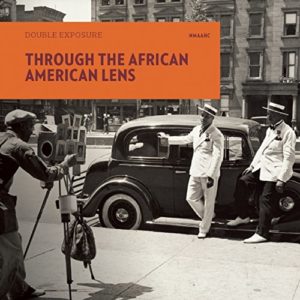

Through the African American Lens is a new book and also the title of a new exhibit that will open at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Both the book and the exhibit are aiming to bring the importance of photography in Black culture and shaping Black history to a new light. Iconic images of Black people throughout history have captured key moments in Black culture, powerful moments of activism and helped create a more complete story of the community’s ongoing fight for equality.

“The book essentially reflects the vastness and the dynamism that is the subject matter of the museum,” said Rhea Combs, curator of film and photography at the museum, according to Time.

Combs served as the head of the daunting task of selecting only 60 iconic photographs out of the 15,000 images that were available to use in the book.

The images themselves harness much artistic value, but Combs explains that the power of the photographs goes beyond their visual appeal. Photography was yet another creative platform Black people used as a way of “inserting themselves into a conversation” in a society that “oftentimes dismissed them or discounted them.”

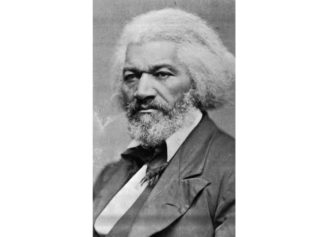

“There is a real, conscientious effort with individuals that are standing in front of the camera to present themselves in a way that shows regality, a fortitude, a resolve,” she added, much like the dapper Black gentlemen in one photo that captures a candid moment from the Great Migration. In fact, she says, Frederick Douglass always made sure he approved of any photos that were taken of him before they were distributed.

White photographers were also a part of a movement that helped change Black culture through photography. White abolitionists were also known to use the medium to capture the atrocities of slavery in order to persuade more white people to change their perspectives.

“During the mid-nineteenth century, abolitionists mailed out photographs of slaves in an effort to change hearts and minds on the matter of abolition,” Time reported.

Sifting through such a wide array of photos captured by both Black and white photographers made it difficult to narrow the selection down in a way that would broadly capture what the medium was able to do for the Black community. That limitation is why the book will continue on in a series that will feature more tailored subject matters for each new release.

According to Combs, seeing the images of the past, including one of Emmett Till’s mother at her son’s funeral grasping a handkerchief as tears streamed down her cheek, is another indication of why the push for equality is just as prevalent today.

The images of Till’s mother, mourning the loss of her son who was the victim of an unspeakably brutal and racist attack, looks all too similar to images that have been captured of Black mothers today who have lost their sons to police brutality.

“Especially on the heels of things that are happening now, this story unfortunately — how many years later — feels very, very familiar,” Combs added.