ABS Exalts Black History: Part VI

For the 2015 edition of Black History Month, we asked a team of talented writers and scholars to mimic the dance of the Sankofa bird and carry us back to our roots so that we may move forward.

We are presenting their efforts throughout February in an impressive array of pieces that reveal to us from whence we came and where we might want to go. There is nothing quite so edifying and necessary as African history, for its grandeur is spectacular in direct proportion to the depths of scarcity we were trained to believe in the New World. It is as essential to us as the air we breathe. We asked our writers to use as a template the words of Langston Hughes, who penned “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as a 17-year-old boy crossing the Mississippi. Hughes uses the metaphor of the river as a way to trace the splendor of African people. Here at Atlanta Blackstar, we see these as words to live by:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

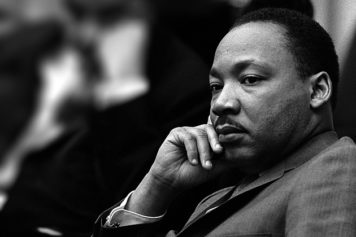

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Exploring Black Consciousness: A Medicine With A Cure For The African Soul And Mind

By Melanie McCoy

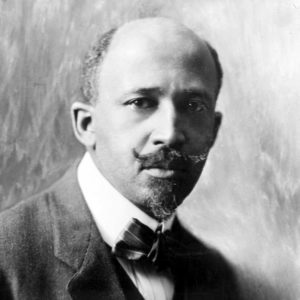

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is a cut-to-the-bone poem written by Langston Hughes that employs importance for reasons beyond the praises given to the accomplishments of Africans before our encounter with America. Published in 1921, Hughes, 17, wrote this poem, his first as a suggestion by novelist and editor of The Crisis, Jessie Redmon Fauset, as a dedication to W.E.B. Du Bois for The Crisis (David Levering Lewis in “The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader,” p. 256). The “river” suggests an idea richer than the Nile or the Mississippi. This “river” engages the spiritual nature of people of African descent regardless of time or location.

Poet and scholar Onwuchekwa Jemie in “Langston Hughes: An Introduction to the Poetry” states, “The rivers are part of God’s body, and participate in his immortality.” Hughes repetitively says that he has “known” these rivers, suggesting that he has never forgotten them utilizing the Akan word Sankofa, “to go back and fetch it,” which further means that in order to move forward as people of African descent we must consider and never forget our past; what and who came before us.

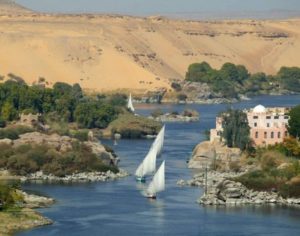

The “river” is functional; it has multiple uses. “I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep” exposes the spiritual nature of the river, which brings Hughes peace. “I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it” discusses ancient Kemet and the “river” as Spirit being part of the divine cosmic order. The “river” or Spirit provided the intellect, strength and creativity for Africans to build the pyramids. “I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset” displays how the “river” or Spirit can provide freedom and liberation.

Scholar and associate professor of African American Studies at Temple University, Dr. Kimani S. K. Nehusi, in “The African Union Ten Years After” states in “Humanity and the Environment in Africa”(p. 369), “Spirit animates everything, and when the material person or thing is no more, spirit alone continues, on a higher plane.” In regards to Hughes’ poem, Spirit has animated the “river.”

“Spirit is first and foremost; animate and inanimate life, in all its variations, amount to but differing manifestations of spirit,” states Nehusi. “However, the poor vision, understanding and self-centeredness of some humans have led them to try to place themselves at the centre, above all else and therefore outside the cosmic order.” Although Hughes might not have had in-depth knowledge of African spiritual practices, this poem suggests that there lies an ancestral memory of it given his appreciation for the “river.”

Nehusi explains (p. 370):

“It is necessary to stress that this awareness of spirituality, this oneness, connectedness and interdependence of everything in the cosmos, compelled Africans to live in respect for and in harmony with the physical environment. Humanity lives in this environment, a habitat that is absolutely necessary for sustaining life through the many indispensable resources it provides. It is therefore necessary for the environment to be recognized as a very precious resource bank which needs to be owned and managed intelligently in order to secure a decent and dignified living for all and for all times.”

Some may argue that today’s Black person, in America specifically, has forgotten some of these ideas of spirituality and interdependency, but Du Bois himself as well as other scholars have explanations for this happening. Over 100 years ago, Du Bois in “Souls of Black Folk” provided the concept of double-consciousness, a concept that some would argue is still relevant to today.

“…The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world — a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world,” states Du Bois. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Chair of the African American Studies Department at Temple University Dr. Molefi Kete Asante has a critique of many of Du Bois’ works. Numerous Black or African minds are colonized because of the crimes committed by Europeans over the centuries as well as keeping intact their white supremacist systems and power structures. Through knowledge, knowledge of self, Blacks or Africans hold the key to Black liberation and the decolonization of the mind. Asante in “The Afrocentric Idea” states (p. 137), “Blackness is more than a biological fact; indeed, it is more than color: it functions as a commitment to a historical project that places the African person back on center, and, as such it becomes an escape to sanity.”

In order to remember or fully embrace our Blackness, especially when it pertains to Black scholars such as Du Bois, Asante firmly believes that “all African writing must retrace the steps to home,” which even outside of scholarship can be applied to all peoples of African descent (p.138). Asante coined the term Afrocentricity, which is an ideology that stresses to be African-centered. To be Afrocentric is to attack white supremacy and Eurocentric ideals, but that is not the purpose of Afrocentricity. The purpose of Afrocentricity is for Blacks or Africans to embrace and celebrate who we truly are, because this is true liberation. Black consciousness is a medicine with a cure for the African soul and mind.

“The Europeanization of human consciousness masquerades as a universal will,” states Asante (p. 138). “Even in our reach for Afrocentric possibilities in analysis and interpretation, we often find ourselves having to unmask experience in order to see more clearly the transformations of our history.” Nehusi also has a similar sentiment in “Humanity and the Environment in Africa.” He states (p. 365), “Africa must return to itself if it is to regenerate itself and benefit from its full capacities again.” Nehusi refers to people of the African diaspora as Africa because we are belonging to it.

Hughes with his poem pays homage to the “river,” which is the antidote to Black suffering. Understanding our history is what brings Africans of the diaspora closer to the “river,” which would resolve and reverse the adverse effects on Africans caused by Europeans, white supremacists and those with anti-Black sentiment.

The “river” is representative of Black liberation.

Works Cited

1. Asante, Molefi Kete. “The Afrocentric Idea.” Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1987. Print.

2. Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. “The Souls of Black Folk.” Oxford University Press, 2007.

3. Jemie, Onwuchekwa. “Langston Hughes: An Introduction to the Poetry.” Columbia University Press, 1976.

4. Lewis, David L., ed. “The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader.” Penguin Books, 1995.

5. Muchie, Mammo, and Kimani Nehusi. “Humanity and the Environment in Africa.” “The African Union Ten Years After: Solving African Problems with Pan-Africanism and the African Renaissance.” Oxford: Africa Institute of South Africa, 2013. Print.

Melanie McCoy is a writer, painter, community activist and organizer, radio personality and the president of OAASUS (Organization of African American Studies Undergraduate Students), majoring in African American Studies at Temple University. She studies and researches methodologies and subjects such as Afrofuturism, Afrocentricity, Black female theories and sexuality.