This profile is part of an ongoing series of narratives focused on men and women who have been killed by the police. It is an attempt to counteract media bias, which often vilifies these men, women, boys and girls. These stories have been captured through the voices of the victims’ family members. I have been fortunate to meet the families through my activism in the Black Lives Matter movement and through work in various organizations.

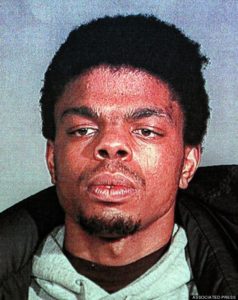

Even before Michael Brown was gunned down in Ferguson, Missouri, the name Ferguson was analogous to police violence and murder. On March 1, 2000, the unarmed Malcolm Ferguson was gunned down blocks from his home in the Bronx.

“Malcolm was my biggest baby,” laughs Malcolm’s mother, Juanita Young, who is a parent to four other children.

Malcolm was born on Oct. 31, 1976, in the Bronx. “He was a loving, happy-go-lucky little boy,” Young explains. He trusted his loved ones, and Young giggles as she tells of a time Malcolm was convinced by his brother that he was Superman. He then attempted to fly out the window. Young recalls when Malcolm discovered Santa Claus was his mother, and instead of crying, he laughed and was happy all the same. He loved his mother.

“He was always worried about me because I’m legally blind. He was very close to his sisters and brothers because his father died when they were young,” Young says.

Malcolm was Young’s second to oldest son—her oldest, James, was 11 months older than Malcolm. Malcolm and his brother developed a strong relationship, but it was Malcolm who took on the leading role of big brother and acted like a father to his three younger siblings when their own father was not around. He went to great lengths to take care of his mother as well.

Like many boys, Malcolm loved to play basketball and liked to ride his bike, exploring different areas of the Bronx, all while protecting his family.

“We would tease him because he didn’t go with lots of girls. He would say that if anyone would do anything to his sister, he would be so defensive. So, he didn’t want to just go with any girl,” says Young.

With a kind-hearted and devoted character, Malcolm grew up with lots of friends and felt pressure from his peers to have more name-brand things. Like many of his peers, he decided to sell drugs for some extra money. He ended up being arrested and serving eight months in prison for drug-related offenses when he was 17 years old. It was in prison where Malcolm finished his high school degree.

Malcolm was so negatively affected by his time incarcerated that he vowed never to return to prison. “He would lay at the corner of my bed and tell me the different horror stories and said, ‘I don’t [ever], ever want to go through that again,’” Young recalls.

Malcolm, then only a teenager, and Young spoke every day while he was incarcerated. Young had a miscarriage while Malcolm was locked up, and she remembers how guilty Malcolm felt. He felt, as the protector, that had he been home, perhaps the baby would have been born. Malcolm did everything in his power to ensure the safety, security and well-being of his beloved family—of his cherished mother.

“There is so much now that I do that I wouldn’t have to do if he were alive. If I would go to the laundry, he would go. He would ask me, ‘Ma, wait until I come back.’ Because of my blindness, he really protected me. There were so many times I had been beat up or whatever, and Malcolm felt the need to protect me,” Young explains.

One time, Young was standing outside of her building when someone asked her for directions, and as Young began to search through her purse, Malcolm was at the window, banging, urging the passerby to ask someone else, out of a fear that she could be robbed. He would leave no opportunity for anyone to take advantage of his mother.

It was not just Young and her other children Malcolm sought to protect. “Malcolm wanted to be a paralegal to help people after what he witnessed in prison. He felt he wanted to help people who were incarcerated,” Young says.

Upon leaving prison, Malcolm took an honest job at a car wash, so that he could make money as he pursued a career as a paralegal. His mother was content and knew that his brief stint in illegal pursuits was done.

“It was better than him asking me for quarters,” Young jokes, “I used to go to Atlantic City with my friends. He always would say, ‘Mom, do you have quarters around here?’ ”

Like many formerly convicted people, Malcolm was constantly harassed and profiled by the police after his time in prison. The young, 6-foot-1 Black man was continually harassed by the NYPD in the Bronx despite no involvement with crime or any illegal activity.

“Every time the cops arrested him, the judge would let him go because he wasn’t doing anything. The judge wouldn’t even buy it,” Young says.

One time, the police arrested Malcolm and instead of properly placing the handcuffs around his wrists, the police aggressively placed them over his thumb. His thumb was so injured that Malcolm had to be taken to emergency services. In response to the violent act, Malcolm decided to take legal action against the NYPD for his injuries in police care. He was still involved in the lawsuit when he was killed. After the lawsuit began, the police harassment increased.

“He still kept coming home and telling me the cops were bothering him. He couldn’t go nowhere without the cops stopping him,” Young explains.

When 23-year-old Amadou Diallo was shot and killed by the NYPD in the Bronx in February 1999 (also unarmed), Malcolm was angered and disturbed, like many in New York. He joined in the massive rallies in 2000 when Diallo’s killers were acquitted.

“He saw how the cops treated him and his friends. He knew what happened to Amadou was not right,” explains Young.

That day, Young was alerted by a friend to turn on the TV and was subsequently told that Malcolm would not be coming home.

“I saw [the police] dragging [Malcolm] on the ground arresting him [for peacefully protesting],” Young says.

Then the police started to come after Young. They began pressing seemingly ridiculous charges against her (one such charge was walking a dog without a leash). Young insists that the police would do anything to get her away from her apartment.

On March 1, 2000, about a year after Diallo’s death, just several days after the acquittal, Young was approached in her home by a police officer who told her that Malcolm, her loving son, her protector, was found dead in the hallway of her building. (Young would later find out that Malcolm had been killed, shot in the head, in the streets.) The shock sent Young into respiratory arrest, and she ended up having to go to the emergency room that same night.

Young claims that the police had been threatening Malcolm because of the legal action he was taking against the NYPD for their brutal arrests. Malcolm was unarmed and was not involved in any illegal activity. He did not attack a police officer, nor did he try and resist arrest, as he was doing nothing wrong to warrant arrest. Malcolm, presumably on his way home from work, was approached by Officer Louis Rivera, a plainclothes officer, and then shot in the street. Witnesses attest to this story, although the police claim Malcolm was shot in an apartment building while selling drugs, and then was shot in a struggle between himself and Officer Rivera. There were no drugs found on Malcolm.

Malcolm is remembered as a brother to James, Saran, Buddy and D’Nai. He was an adoring son to his mother, who has worked nonstop since 2000 on his behalf to fight for greater police accountability and to end violence rooted in racism at the hands of the police. Malcolm himself had hoped to work with the legal system to advocate for those most brutalized by the system. Instead, his life was cut tragically short.

The police officer who murdered Malcolm still is a police officer. Young continues to fight on Malcolm’s behalf.

“I think about what he would be like today. What joy he would have brought me,” Young says.

Tess Raser, originally from Chicago, is a teacher in Brooklyn and an active member of the growing Black Lives Matter movement. She works with various groups, including We the People and the Stop Mass Incarceration Network.